Maurice Berger and Marvin Heiferman in 1997. Portrait by Mitch Epstein

Approaching the one-year anniversary of Maurice Berger’s COVID-related death, his husband, photography curator and critic Marvin Heiferman speaks about their shared passion for photography, social justice, the ubiquity of image-culture, and life itself.

Early in the COVID pandemic, the photo community lost one of its brightest lights. In late March 2020, writer, curator, and staunch social justice advocate Maurice Berger died at his home in Craryville, New York.

Berger’s 1990 Art in America essay “Are Art Museums Racist?” helped contextualize contemporaneous conversations about race and representation across the art world, but specifically in institutions that predictably fail to acknowledge and correct racist practices and procedures. From 2013 through 2019, Berger’s award-winning column, Race Stories, for the New York Times Lens Blog championed the photographic works, books, and projects of people of color.

Berger’s premature death opened a gaping hole in the lives of those who knew or admired him, but none wider than his husband Marvin Heiferman.

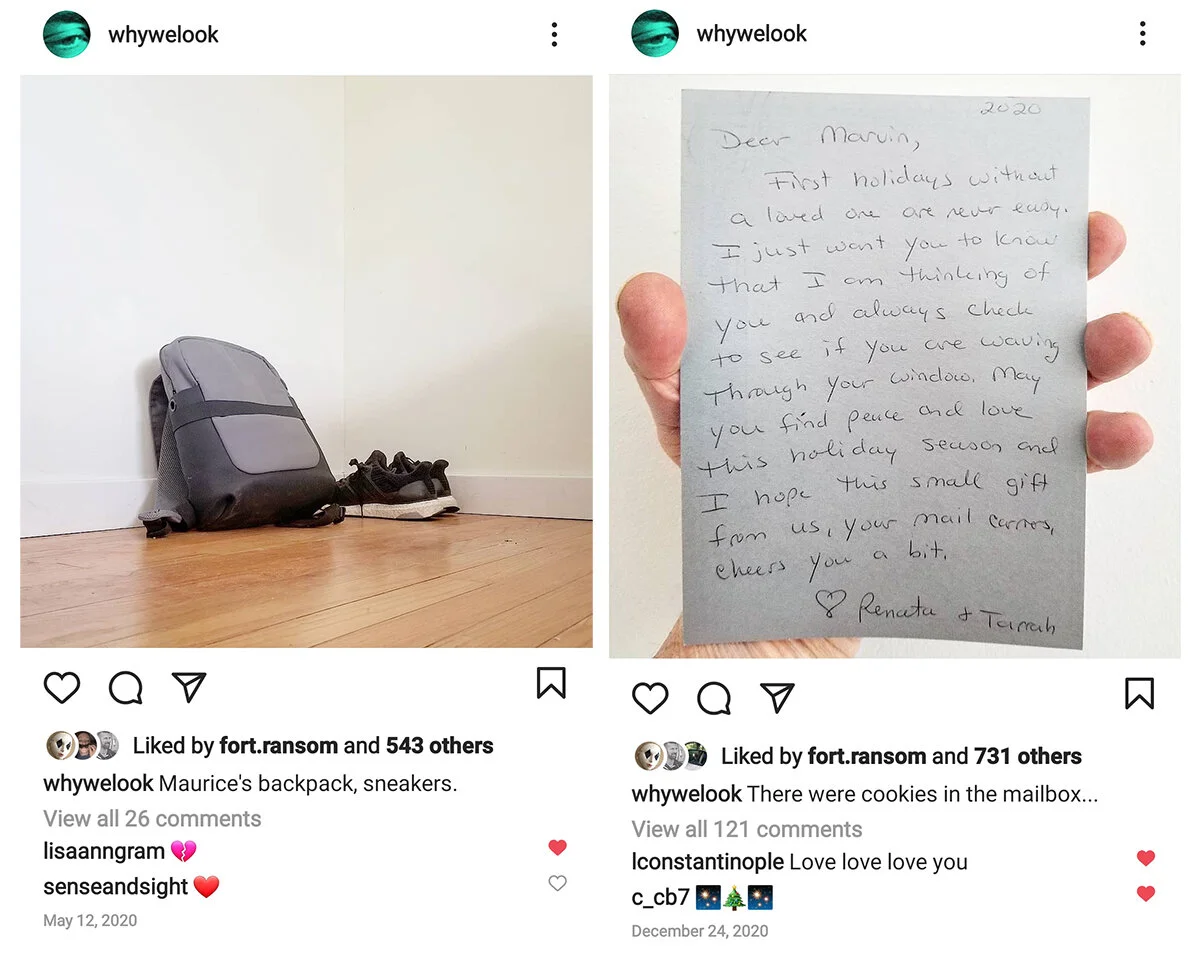

An equally revered writer and cultural commentator, Heiferman started sharing candid visual reflections on Instagram via @whywelook shortly after Berger’s death. Photos of life with Maurice, and without him, convey harrowing loss as adequately as images can. Their wedding rings stamped with “Love Mo, Love Marvin.”

A photo of Maurice’s favorite plaid vest captioned “An easy picture to make, but so sad for me to look at…” Marvin’s first view into the couple’s New York City apartment after Maurice died. These pictures frame social media and photography as spaces for processing grief and engaging community.

Marvin Heiferman graciously agreed to speak with me about his loss, and how he is coping nearly a year on.

Roula Seikaly in conversation with Marvin Heiferman

Courtesy of Marvin Heiferman

Roula Seikaly: For anyone who doesn't know who Maurice was, could you describe him? How did you guys meet and what was your marriage like?

Marvin Heiferman: Maurice was a writer and a cultural historian. His degrees were in art history, but over time he became increasingly focused on the way photographic images worked in culture-at-large and particularly when it came to race and representation. He curated ground-breaking exhibitions, wrote influential articles and books, and did pioneering online projects. He was an amazing guy.

We met, as it turns out, twice. He told me that the first time, which I didn't quite register, was at an event I did with Barbara Kruger at ICP in the mid-1980s, which she was nervous about, so she brought along a friend, Maurice, with her. I only vaguely remembered that because he was very tall, skinny, and bearded at that time. And what I also didn’t know was that he’d had a crush on me and seven years later in 1993, a friend set us up on what I thought was a blind date, although Maurice had, in fact, very cleverly engineered it.

Seikaly: And were you together pretty much from that point forward?

Heiferman: Yeah. We had one lunch together, a three-hour lunch, and each walked out the door thinking, "This is it."

Seikaly: Aw, that's lovely. And you were married sometime after gay marriage was made legal in this country?

Heiferman: As soon as it became legal in New York in 2011.

Maurice Berger and Marvin Heiferman, 1998 © Lyle Ashton Harris

Seikaly: You're an observer of visual culture as well. Did your work influence his and vice versa? How would you describe that?

Heiferman: We looked at and talked about images and imaging all the time. Maurice was a protégé of Rosalind Krauss in the City University of New York’s Art History Program, worked on minimalism and contemporary art, but ultimately came to find that limiting in terms of his personal experience and more compelling interests in race. When we met, he was working on Adrian Piper's first retrospective and other projects for the Center for Art, Design and Visual Culture in Baltimore, Maryland.

I had started out my career in the 1970s and early 1980s as a gallerist and photography dealer, then went on to curate numerous museum shows and run a small publishing company, all the while becoming increasingly interested in how photography, in all its guises, shapes people’s lives, work, and culture at large. Maurice and I met at what were pivotal times for each of us, watched each other's work evolve, and not only talked about, but impacted each other's work a lot. A lot.

Seikaly: When social media and particularly Instagram became a pervasive, image-forward platform, did that change your work, his work, and the dialogues that you were having about image-making and consumption?

Heiferman: Maurice was an early proponent of social media and using the Internet as a forum and conceived and produced some of the first online art conferences for the Whitney and Georgia O'Keeffe Museums. He was always active on Facebook. It wasn’t until 2013, when I was at a conference where Kathy Ryan from the New York Times and Lesley Martin from Aperture and they were constantly posting to Instagram, that I got curious. And I started posting pictures regularly, one a day, in 2014.

I'd been working in and with photography for decades, but I started out wanting to be a painter. And I’ve ended up being a very different kind of cultural producer. Instead of making pictures, I became more intrigued with conceiving and producing photography exhibitions and publications that would make people look at, think and talk about pictures. Although I’d been posting daily links to stories about visual culture on Facebook and Twitter, Instagram was the more logical social media platform for me. And since my phone was also a camera, I started taking and posting pictures.

Maurice didn't join Instagram until a couple of years later, when his Facebook practice got big, more political and intense and he recognized that Instagram was yet another platform to help get his ideas out. I enjoy the platform most of the time, because it allows for an interesting dialogue about images and photographic attitudes. But it’s got real limitations. I hate the manipulative algorithms that make assumptions about what you’d like to see and are designed to keep you looking. Facebook’s ownership continually pushes the app away from photography and towards video, messaging, and shopping. And I don’t trust Instagram’s long-term reliability as an archive.

That said, I love the sense of community on Instagram, of being able to show and share what you’re looking at, thinking about, and how you decide to picture all that.

Seikaly: Absolutely.

Heiferman: I look forward to the daily interactions with image-makers, editors, curators, and people from all over the world and the opportunity for us to look at pictures together.

Maurice and Marvin - a triptych from 1995. © Joann Verburg

Seikaly: That leads into a question about your Instagram account, @whywelook, and how you use it. It sounds like you're both a consumer and someone who’s trying to understand why we look and what we look at. Not just in a fine art context, but perhaps more broadly defined. We’re visual animals, and spend so much time on social media, and Instagram feeds our desire to be looking constantly. Does your Instagram activity reflect your professional and personal curiosities, as far as visual images are concerned?

Heiferman: It's all of that, and, in a formal sense, my interest is a throwback to the time I was an artist making square paintings and works on paper. Because I’d worked with so many incredible photographers—including Harry Callahan, Eve Arnold, Mary Ellen Mark, Robert Adams, Peter Hujar—who shot square pictures, I had a pretty good understanding of what makes square photographic images work, or not. I’d also done a number of curatorial projects for Polaroid, so had access to SX 70s and lots of film, so the options and limitations of square-picture-making was something I played around with and was fascinated with.

My interest in Instagram was also, in a way, an extension of a project I’d done at the Smithsonian, Photography Changes Everything, which enabled me to explore how photography functions for different people and communities, something similar to what makes Instagram, as a platform, compelling. I was interested to see, too, how the people who initially seemed to be the most ambivalent about Instagram were art photographers who were uncertain about how to maintain their identity as serious picture makers on the new app and chose to represent themselves on a minuscule-scaled platform to undefined audiences.

Seikaly: Fast forward to early 2020. Is there anything that stands out in the conversations you and Maurice were having about what was there to be absorbed visually?

Heiferman: No, ours was an ongoing conversation, whether we were in a museum, the car, a supermarket, or watching reality TV. We talked about images—why, by who, for who they were made, why they worked--all the time. I think that I opened Maurice up to looking at a wider range of images than he had previously and I know I learned to be much more critical in the ways I thought about representation because of him.

Seikaly: And then he got sick…

Heiferman: In late March 2020. Early in the month and as talk about and fears of COVID spread, we were in Manhattan. On March 12th we decided “Let’s get out of here,” and went to our house in upstate New York, where we thought we’d be safer. Five days later, Maurice felt tired, but we thought, “Everybody's nervous. We're all freaked out. Let’s try to relax, we’re home.”

But on Wednesday, March 18th Maurice woke up with a fever and began texting his doctor, asking what we should do. He was nervous. I was too. His fever continued on Thursday. On Friday night, he felt a little bit better, and we were watching TV. On Saturday, he’s not well and on Sunday, he's in terrible shape and by 5 o'clock or so, he's dead. That's the very short version. What happened was horrible.

Seikaly: I'm sure it was. Were you at home or was he hospitalized by this point?

Heiferman: We were home. Nobody knew much about COVID or how it could be treated, at that point. Doctors were saying, "Unless you're in respiratory distress, don't go to the hospital."

Seikaly: I was already following your Instagram account because I'm an avid fan of your writing and curatorial work, and I’d noticed that something had changed in your pictures. Did you start photographing what was going on immediately?

Heiferman: No, that took a couple of days. It's interesting to go back and see what I posted on the days Maurice was sick. I can see my own hesitancy as to what to put up, but I had a routine and tried to stick with it. But there was only so much I could do. Because Maurice was sick and in bed, I went outside and took a photograph of my neighbor, socially distanced and standing far away from me behind the house.

I did take one picture of Maurice under the covers the day before he died, that hurts to look at and that I may never put up.

Maurice died on a Sunday night at the beginning of a pandemic. I came home to an empty house and Instagram was, as you can imagine, the last thing on my mind. It was three days later that I realized I had to get out and went for a walk down the road. There’s a little cabin there with an American flag hanging on a tree near it. I'm looking at this American flag in the middle of a Trump-fueled COVID nightmare and it’s twisted around a pole. And I'm thinking, “That's fucked up and I'm fucked up,” and could barely talk about, let alone articulate, what was going on or what I was feeling.

But there was something about the flag that matched the way I felt, so I took a picture of it. I would not normally be taking pictures of American flags because the symbolism or clichéd irony is way too easy. But I put it up on Instagram and went to sleep in the bedroom next to our bedroom because I couldn't make myself walk into that space...

Courtesy of Marvin Heiferman

Seikaly: Of course.

Heiferman: Waking up in our house and alone was horrible, but I started to think that if everything seemed completely out of control, Instagram might be a regular thing I could do that would ground me. I soon realized, though, that I was in no frame of mind to make any "Oh wow! Look at this, isn't that interesting?" kinds of pictures.

I was, all of a sudden, seeing things differently because I was surrounded by situations and stuff whose meaning had changed overnight. I was only able or interested in taking pictures about what I felt like and of things that reflected the emotional upheaval and vulnerable state I was in. It became the only thing I was doing that made sense to me. I could barely eat or sleep, but making pictures made sense to me.

What was curious was that the pictures I started posting began to connect with people on Instagram in ways I didn't expect at all, at all. The numbers of likes I was getting quadrupled, the number of comments started escalating. People were loyally watching me go through something and it touched them in ways neither they nor I expected. People seemed to be watching out for me and wondering how I was feeling.

And I decided not to hold back. I’ve never been the kind of guy to wear my feelings on my sleeve, but that’s what I was doing visually. People talk about and criticize Instagram for being a branding exercise and there I was, I guess, a grief guy on Instagram. For all the talk in the media about death and dying, most people didn't personally know anybody whose life had been impacted or someone who had died because of COVID.

Now they did.

Seikaly: In the most immediate way possible, COVID touched your life.

Heiferman: People started commenting and sending messages to me: “we feel sorry for you, we’ve got your back. we love you, what you’re doing is so brave.” But I'm thinking, "This is a survival technique. I'm vulnerable and I can't stop myself from being that way.” What was going on didn’t dawn on me, at first, because I’d never had that many comments on Instagram, so many hundreds of likes and comments. That was incredible to me, because grief is such a disorienting state that I was grateful that instead of spending all day thinking "How am I gonna get through today?" there’d be a few moments when I’d have to think, “What picture am I gonna put up today?"

And I also started writing captions for the pictures, which I'd never done before, all to try and see and feel my way through things. And it was, and still is, hard at times not to become self-questioning and self-conscious about what to put up. Maurice was a public figure, but a very private person. People know him as a brilliant and compassionate guy, which is true, but I also know Maurice as the hilarious, often goofy, sweetheart of a guy.

Seikaly: Sure. [chuckling]

Heiferman: How to balance that out? Maurice was very careful in curating his public voice and persona. What’s more urgent and important to me is to remember and represent our life together. You don't often see a gay love story like ours represented on Instagram and because of that, too, people took notice and started are sending me messages. I’d be sitting in bed late at night and somebody in Milan would be writing to me about the story of his lover's death, how isolated he felt when he couldn't talk about it with people he knew, how he had to grieve alone and how heartened he was to see what I’m doing. A straight friend wrote, "I love my husband but I look at the love you had for Maurice and realized my marriage is a mess."

Over the months, I’ve come to realize that what I’m telling is the story of Maurice and me, but that it’s also a story about photography and love, death, loss, politics, and the pandemic. That’s when I started thinking that what I was doing has got to be a book and started doing some research about the nature of grief. I came across the work of one expert, David Kessler, who often speaks about the fact that grief needs to be witnessed, which rang a bell because, I realized, that’s exactly what I needed and was doing, as best I could--to have people by my side, even in the midst of the pandemic.

I was, essentially, alone in the country, except for my immediate neighbors and, occasionally, a handful of friends and family members. But what I needed to feel comforted was to have people more regularly alongside me and it turned out that one way to do that would be to share my experience through pictures and on Instagram. Instead of showing off my life, as many people do on the app, I realized I could use the platform in a different way. It's not that people weren't doing that before, but I certainly wasn't and most people I knew weren't.

Seikaly: Maurice was so deeply loved as a writer, curator, and artist advocate, especially where matters of race and representation in photography are concerned. Did you feel obliged to share your grief?

Heiferman: An interesting word…

Seikaly: When he died, there was suddenly such a vast un-fillable space for us who have looked to his writing as revelatory. I can only imagine what that's like for you. I wonder--as you process grief and considering how slowly that often proceeds--do you feel like there's something that's owed perhaps? Maybe that's too transactional a way to describe the relationship.

Heiferman: No, it's an interesting question and that's why the word “obliged” is a tricky one. Maurice and I had our professional lives and our personal life. I’m using Instagram largely in a personal way, and so only tangentially hint at the story of a kid who grew up poor, dreamed of being a public intellectual, figured out how to do it, and succeeded brilliantly at it.

Seikaly: Beautifully.

Heiferman: After Maurice died, and given the nightmarish events and politics regarding not only COVID, but of racial injustice that were going on, people were continually wondering out loud, "What would Maurice say? What would Maurice be thinking?"

And I'm sitting there thinking, "Don't fucking ask me that, he's dead, I can't deal with that now. My loss is different: personal, devastating."

Whenever I would hear Joe Biden talking, between the time of his nomination and election, about his son Beau’s death and how hard it is to continue, how you needed to have a sense of purpose, I’d sit there in tears, wondering what mine was. And soon after I thought, "Well, I'm making thousands of people think about Maurice every day." So, what I’m doing is not out of obligation. I’m honoring him. I’m honoring us.

Maurice Berger and Marvin Heiferman in 1997. Portrait by Mitch Epstein

Seikaly: That's beautiful. It's in so many ways, your story, your relationship, the way that he became sick and died—is a condensed narrative for so many people who have faced the steam-rolling catastrophe that is COVID. What you share of yourself, Maurice, and of your life together really brings a lot of that into focus: the minutia, the beautiful and, at times, small or seemingly mundane details that describe the essence of a person, what goes into a relationship, a marriage. And when that's all suddenly gone, it becomes so much more profoundly meaningful.

Heiferman: One related thing I do want to talk about briefly is how my Instagram pictures fit in the public versus private depiction of what COVID is.

Seikaly: Absolutely.

Heiferman: COVID ended Maurice’s life and upended mine. And COVID was and is still being denied by some. When Maurice died. I could not get the local coroner or medical examiner to swab his body, to do an autopsy. And so, Maurice’s death is one of many that are not reflected in the official numbers. I'm watching the whole COVID thing explode all around us and watching how the story gets told in the media and realizing it's very hard to make anybody understand what this is like to go through.

When I went to pick up Maurice’s ashes, I stood by, horrified when the funeral home employee who handed them over to me said, “COVID’s a hoax.” For me, the media pictures that come closest to getting at what was going on, what this experience felt like, were those made at nursing homes and hospitals where people were separated by a pane of glass from those they loved, who were dying on the other side of it.

Maurice, 2015 © Steve Miller

Seikaly: How COVID-19 and the pandemic are represented in the media doesn't sound like it's something you want to engage with immediately, which makes perfect sense. Do you think it might be in the future, given the observer of visual culture that you are?

Heiferman: I'm thinking that in the book I want to do, I’ll have to write about the way COVID’s been represented in the news, just as I’ll have to deal with Donald Trump’s statements about COVID not being a problem.

Seikaly: The book sounds like it’s a compelling project for you, although it must be odd to feel anticipation or joy about something that you will produce because it comes from such devastation and loss.

Heiferman: It is. My friends are saying "Do it!" And I’m like, "I will, but I don't know if I’m ready... "

Seikaly: You’re not on a deadline.

Heiferman: Well, there's that and the fact that grief’s timetable is unpredictable. It's more than nine months since Maurice died and the only way I’m able to get through this experience is by putting one foot in front of the other. People I talk to who’ve experienced traumatic deaths and subsequent grief say "Your grief is never going away." And I know it won’t and that it will morph, but however the book takes shape, working on it is one of the very few things I look forward to doing.

People have written beautifully about photography and loss in the past, but there’s more to say and these pictures are different from what others have done. I know that my experience is both alike and different than other people's experiences. People tend not to represent themselves on Instagram in this uncomfortable way and what’s interesting about this to me is that I’m not only willing but needing to do that.

Seikaly: You've been very generous with what you've shown us as audiences, is there anything that is simply too personal, too private, too precious to share on Instagram?

Heiferman: Sure. There are some pictures I can’t bring myself to look at now, but may be able to deal with later. On the day Maurice died, I took a few pictures as I leaned against my car at the side of a road and in the cold, near ambulances and the helicopter that arrived to medivac him to hospital, but that he never made it onto it. I was waiting to find out if he was going to live or die and there was nothing I could do. I was like a bystander of my own life, in a situation that felt totally out of control. And I reached for my phone and took a few pictures that I could barely look at the time, and for the most part, still can’t.

Courtesy of Marvin Heiferman

Seikaly: It's simply too much.

Heiferman: There’s the helicopter picture I took right around the moment Maurice died, which took two months for me to get the nerve to look at and post it. I was so freaked out, watching all the people who had been trying to save Maurice’s life just standing around. I was in shock when I took that and some other pictures. And then and on a much lighter note, there’s pictures from over the years, that I won’t put up because Maurice’s hair was messed, because I know he would have hated that.

Seikaly: If my wife got sick and died due to COVID, I wouldn’t have the presence of mind to think in the way that you have as far as navigating grief through images.

Heiferman: You often don't know what you're gonna do, until you do it. But one thing I do know is that photography has repeatedly changed my life. It happened when Harold Jones hired me to work at LIGHT Gallery in the early 1970s. And photography’s continued to do that ever since, in terms of what I’ve looked at, cared about, and accomplished. The fact that I’ve turned to making pictures now--in an unexpected way and as an artist again--was a surprise to me, but if I take a step back, I guess it’s not.

Seikaly: You said at the top of the interview that Instagram is a flawed archive. I'm curious, has this experience changed the way in which you associate the medium with memory, with archives?

Heiferman: Part of what I love about photography is that it's a bundle of contradictions. There's still photographs of life that's moving on. There's a pictorial order imposed on the chaos of the world and here I am, using photography to deal with life and death, past and present in hopes of finding a path to the future.

Photography is a tool, one that works differently for everybody. Making pictures the way I have for this project has been good for me because I simply can't imagine how I’d have gotten through the past months if I didn't. And it seems to be working for other people who are plugging into it, too, because there’s so much grief all around now. Everyone’s in such an unsettled state.

Seikaly: Absolutely.

Heiferman: Some years ago, when I was developing the Smithsonian project, there was a transformative moment when I met an anthropologist who talked eloquently about photography as an active agent of cultural and social change. Once I absorbed what she was saying, it changed the way I thought about the medium...

Seikaly: Oh wow!

Heiferman: That was about a dozen years ago and now photography is actively helping me live and think about my life, every day.

Marvin and Maurice at the Met, 2017 © Therese Lichtenstein

Seikaly: I was going to ask if there's anyone either on Instagram or an artist that you were looking at with interest before Maurice's death or now, given the work that you'd been doing since.

Heiferman: There are dozens of people on Instagram who I follow and admire because they're so inventive and brilliant at it. But then there’s a handful whose work has touched me deeply, especially in the ways they deal with loss like Pamela Vander Zwan’s @ahusband.adeath.acountryboy, Tanya Marcuse’s photographs of her ailing mother, who recently died (@tanyamarcuse), and Cheryle St. Onge (@cherylestonge), who’s been photographing her mother, who has vascular dementia.

Seikaly: One last question for you, if you feel like talking about it. What do self-care practices feel like for you? I know the way you described it, photographing is certainly a huge part of that. Is there anything else that is helping you navigate all of this?

Heiferman: I talk often and at great length with people who've lost spouses and experienced PTSD, as I have, and who have become grief-buddies. I’ve learned to be self-protective because while people are well-intentioned, we’re so uncomfortable talking about death in our culture that we don't know how to do it. So, part of self-care has been to learn to give people leeway, to not get pissed off or disappointed when they say something insensitive because they just don't know how to think through what they're saying or doing.

There's a lot of cooking, long walks, drives, staring out at the Hudson River and local lakes, and talking on the phone with people who know me really well, can’t see me now, but know me even better because of the pictures.

Seikaly: Thank you so much for speaking so generously and expansively about this experience and your relationship with Maurice. I know your goal wasn’t to make this a project, but your pictures provide a unique way for viewers to think about COVID as an intimate and lived experience. So, thank you, it's very much appreciated.

Maurice Berger, 2000. Photo by Robert Giard, Copyright The Estate of Robert Giard