© Ross Mantle

Ross Mantle's Cryptic New Photobook Keeps Us Looking

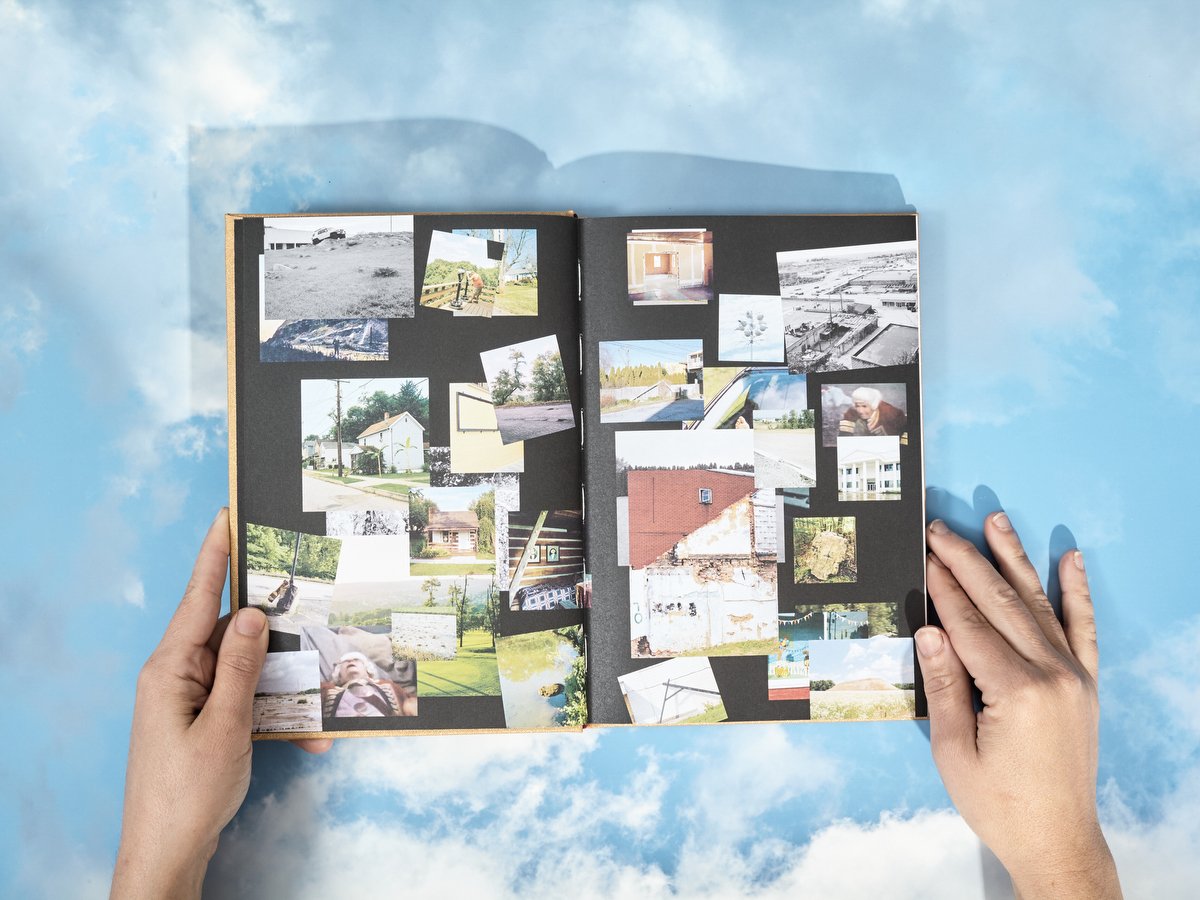

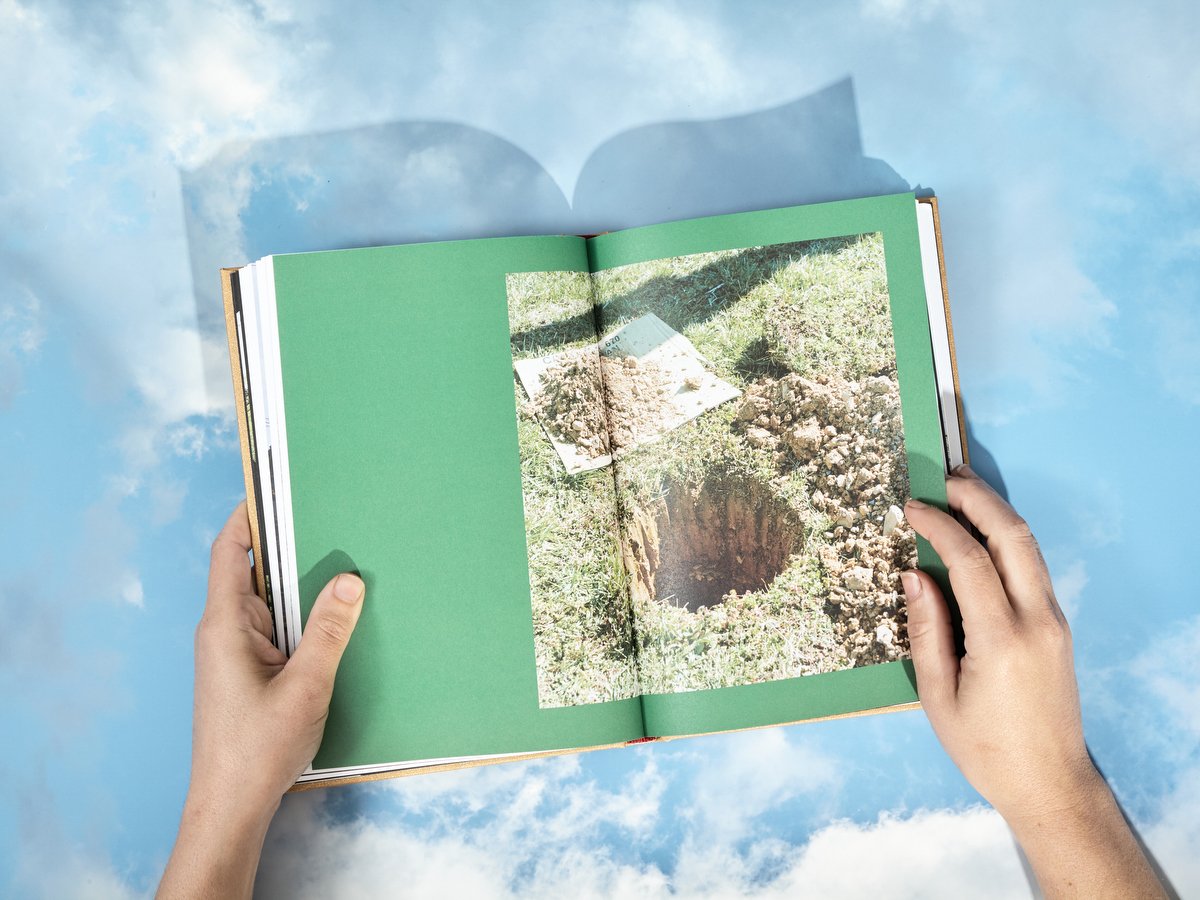

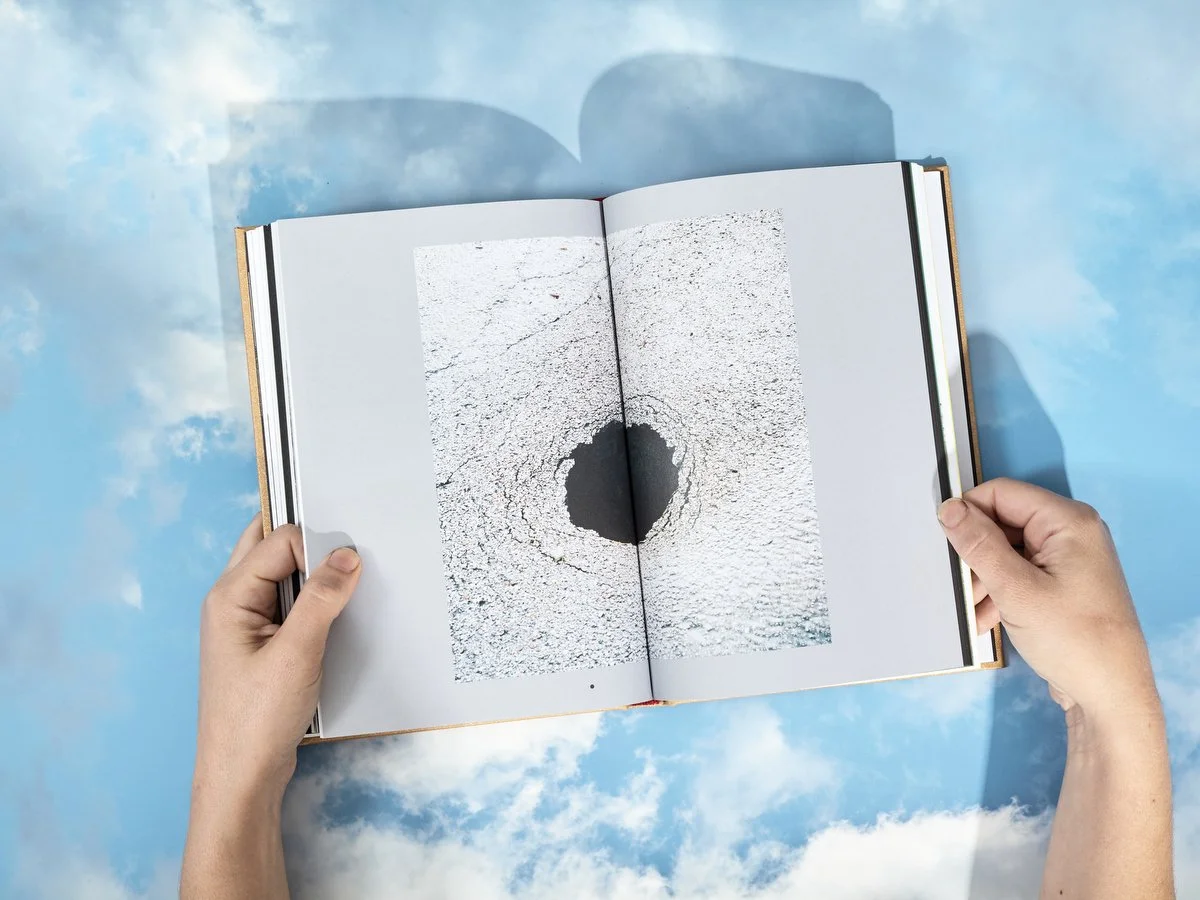

There are often photos that elicit creative envy. The kind of photo with the punch and punctum to pull you in at first tug, but with enough grace to keep you looking and looking again. And to wish you’d taken it yourself. This photo above, with its gaping mix of absence and resolution resonates this way for me. It's one small piece of Misplaced Fortunes, Ross Mantle’s new book of photographs that feel like a magically convoluted puzzle.

Published by Sleeper Studio, Mantle’s first monograph is a meandering collection of visual clues with no clear solution. A found sculpture of a golden ear. Various references to holes - both literal and metaphoric. Anonymous gravestones leaning and waiting for repair. Bodies emerging from the woods. Faces obscured by sweatshirts or wisps of hair. Hints to treasures never to be found – riddles we might never decode.

I corresponded with Mantle to learn more about his mysterious new book.

Jon Feinstein in conversation with Ross Mantle

© Ross Mantle

Jon Feinstein: I keep trying to figure this out. There is a cryptic-ness to this book, almost a code I'm trying to decipher, that never feels like it gets resolved, but in the best possible way.

Ross Mantle: That’s a good summary, and very generous—it’s purposely cryptic and esoteric, filled with codes that vary in how they can be interpreted. Everything has at least a couple reasons for where it is, how it’s used, how it looks, what else it connects to in the book—the cairns, text, each image has multiple entry points. Even the numbering and titles, as nonsensical as they seem, are derived from all the previous iterations of the book and project in its different forms.

Feinstein: There’s a kind of shuffling going on…

Mantle: As the edit shuffled, the numbers (cairns) moved with the images. Some lost their place along the way and occasionally you’ll find an orphan cairn that doesn’t connect, lost to narrative progress. I see it all as a reflection of building anything over time—roads, towns, history, myths—and how those things are passed on, retold, confused, hidden or forgotten.

This multiplicity of meanings was important to me in making this work. Primarily, it’s a way that I can reconcile the major shortcomings and dangers of documentary photography with its beauty and potential as a tool for art and communication. I love how varied the interpretations and possible uses of one image can be over time and across perspectives, but it makes meaning and intention murky and frustrates understanding.

In the process of this project I started thinking about photographs being visually akin to homonyms—words that are spelled or sound the same but have different meanings. This helped me to open up some of my understanding of the work and the ways I could build broader connections across images, text, symbols, all the different pieces.

Feinstein: I love the open-ness of this…the quest….

Mantle: The seeking of a fabled treasure is connected to this frustration. In both modes, the seeking needs to be prioritized over the finding or understanding if it’s to be successful because in the end the gold was probably never lost to begin with.

© Ross Mantle

Feinstein: I’ve been thinking about how your sequences build or riff like song structures. I don't know if you grew up listening to punk/ hardcore, but I once met Jose Palofox, who played drums for Swing Kids, Struggle, and countless others - and he talked about the importance of balancing chaos and quiet - the build and crescendo that makes for a really cathartic and emotional experience of music. I think about that in relation to how you edit and build the tension in this book - the images gradually layering into wildness/ insanity , and then slowing down and pacing and bringing back some calm.

Mantle: I think this is pretty accurate. I did listen to punk growing up and my musical interests have always been varied. The shorter and faster structures of punk songs don’t appeal to me as directly in my editing process but that building and breaking and building back again does play a part. You bringing this back to youth too is pretty important—a lot of those early interests and formative creative exposures are embedded pretty deep.

A lot of what I started listening to in high school still factors in when I’m trying to find some direction with editing. Traffic’s “John Barleycorn Must Die” is one of those records for me—my dad first encouraged me to listen to it as a teenager. I still return to it often and listen to a lot of similar music from that era and that built off that moment. I like the longer and layered compositions of prog/psych/jazz/math rock, but narrative and lyric driven music is equally important to me.

More on the punk/art rock side I listened to Lifter Puller throughout high school and still return to their albums and The Hold Steady’s albums often. I love the way Craig Finn can layer characters and places and build worlds with a band. It’s rewarding as a listener but also lends itself to a lot of humanity over the course of a couple records as you see the comedy and tragedy and ups and downs of these people and places over time and situations.

The Flex and the Buff Result is a great example of that build up and breakdown, chaos and quiet, that you talk about, but it also has this narrative aspect that brings all these different characters to a penultimate exchange at the end of the album and then sort of leaves you hanging. It’s a great song but is made that much better because of the layers built into it and the lack of a compositional resolution.

© Ross Mantle

© Ross Mantle

Feinstein: Now I have to ask the obvious question…if this book had a soundtrack, who would be on it?

Mantle: Hahaha, there sort of is one. I make playlists when I’m working on a project. It helps during the editing process to keep me in the headspace or recall specific music to put on when I’m working in the studio. I also pick up records when I’m browsing with editing in mind—not necessarily something I’m into at that moment, but something I think might be good later on when I’m in the studio.

For Misplaced Fortunes—some of the bands on the playlist were Sea Power, Dylan and the Band, Andrew Bird, Menahan Street Band, Warren Zevon, Felice Brothers, John Prine, Dr. Dog, Battles, Belle and Sebastian, Miighty Flashlight, and the band of some friends, Grand Piano.

© Ross Mantle

© Ross Mantle

Feinstein: I love that!

Mantle: I think the song that I listened to the most during the project was Jim Ford’s Harlan County. This song brought a lot of different ideas together for me in both music and lyrics. It helped me stay focused on key themes and maintaining a consistent tone across the project. There are a couple moments in the song that inspired me to take some risks and include unexpected pieces that maybe only appear once or twice but are pivotal for the work. The song has this amazing way of meshing musical styles and storytelling techniques.

It’s upbeat but dark and has moments of magical realism and mythology mixed in—it’s a surprising and funny song and it subverts a lot of stereotypes about Appalachia. It moves between all of this in such quick succession with some surprising musical shifts. Nothing feels abrupt or out of place though, it’s a complex song that never lets it show.

Feinstein: Yeah - there’s a wandering country/ folk-ness to a lot of the imagery as it relates to abstract storytelling. Can you tell me about some specific images/ songs that tie into this idea?

Mantle: Paradise by John Prine also made its way into the work directly. The story he tells in that song is one of the ways to interpret and look at the landscape and places I was photographing. I was thinking about that narrative a lot as I was photographing. I worked the song title into the Guide Book to make a direct connection in the work in the title of the following image:

97: Pretty Good follows Paradise

The image title references the song sequence on Prine’s self-titled album that Paradise appeared on. This short series of songs struck me. First, looking to the past in Paradise with some nostalgia but more realistically—seeing how all the forces of power work together toward exploitation under the idea of Progress. Then he leads into a beautiful and funny song, Pretty Good, that gives equal credence to the mundane, spiritual, universal, and darker aspects of life. It’s beautiful how his refrain of settling or languishing and seeing every moment, however dull or exciting, as part of the same larger human experience.

I love Prine’s lyrics but his songwriting is so smart in this song—it’s vaguely upbeat but maintains the same tempo throughout and never has a moment of full exultation. It seems to respond to and balance any hints of nostalgia or regret or bitterness playing out in Paradise with resignation but not despair. I hear it as an ode to finding meaning in the everyday in a way that someone like Peabody seeks in the consumption of land and labor.

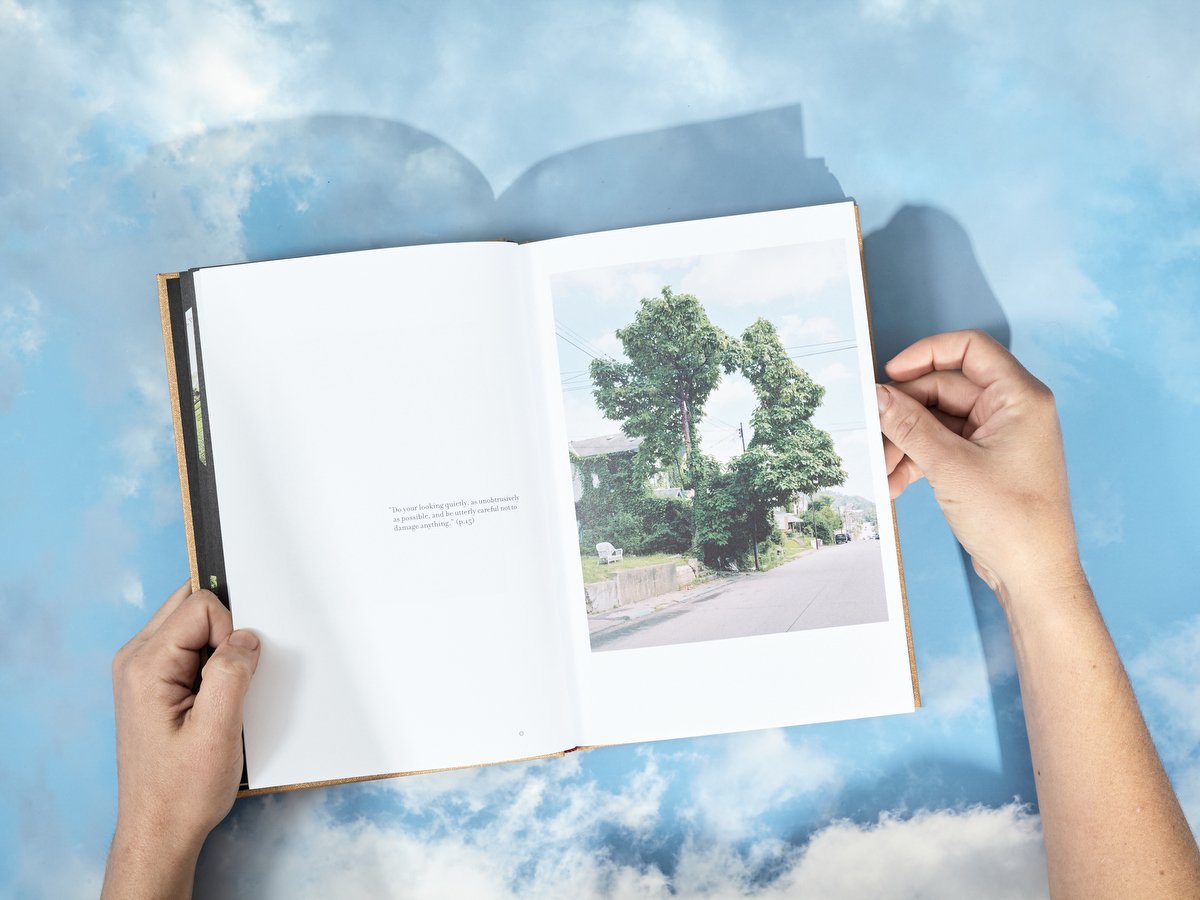

Feinstein: One of my favorite images - one that I am admittedly "jealous" of you having made, haha, is the photo of the tree with a gaping hole in the center. While similar tree pictures have been made by a range of photographers there is something so brutal and disconcerting, yet equally inviting and calming about this picture. I want to devour it, to live with it, to sit in it. What's the story behind it?

Mantle: I’ve noticed it a lot more since I made this photo and also started to realize how many other photographers gravitate to this kind of image too. This is all really nice of you—I don’t know if it’s better than any of the others out there. For me though it was important in this project because of the perfect hole—that’s a really important shape and symbol in this work and this is one of my favorite examples of it in this project. The telephone lines going through the hole also show up a lot—in reference to the “telephone game” of history and mythology and indicative of the complicated landscape a lot of us live amongst.

The image was made in the Braddock or North Braddock area, not far from where Braddock’s march ended—I think this would have been part of the battlefield in 1755. It was such a stark circle and that shape was something I had been looking for specifically as part of the project.

Feinstein: In the book you print it twice, once in color, once in BW, much smaller on the page. What's the reason behind that decision?

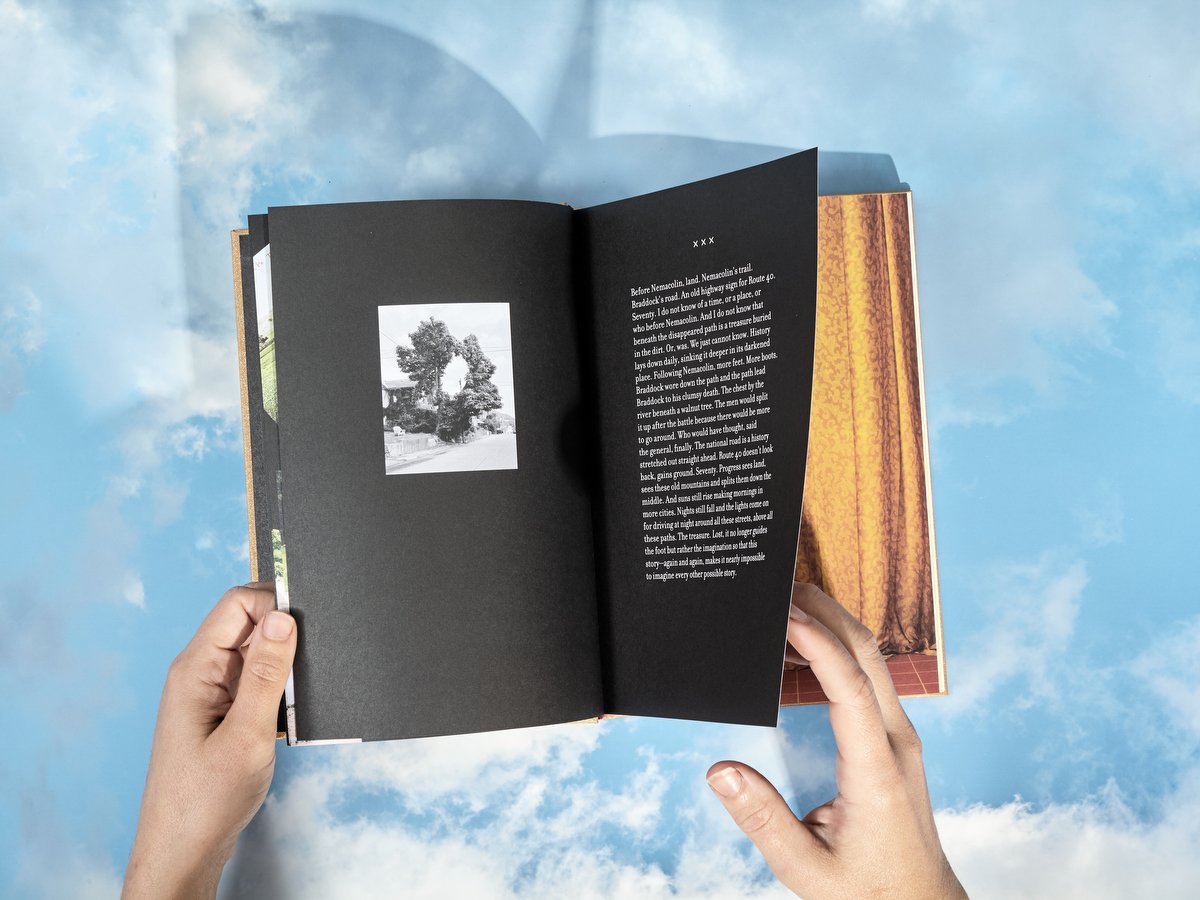

Mantle: There are a few photos that this happens with. It's done to obscure the time, place and broader understanding of the image. There are some historic postcards of Braddock’s Road that I came across in the process of working on the project—they had been hand colored and at times people were drawn in too. I found some of the black and white versions of the postcards. Working off this mix of time and aesthetic, I started applying similar logic to my images. This became one of those that was simultaneously archival/historic in the narrative and also a part of the contemporary narrative.

In it’s monochrome version, it follows the opening montage and sort of introduces the book alongside the semi-esoteric text about highways and Braddock and speed limits and American Progress. It’s another key to the book in that so many repeating themes and elements are present in it. This opening text was made through a game of telephone between Edith and myself. I wrote a draft of the initial text and sent it to her and we went back and forth a few times. It was important that she write the introduction in her tone so that it matched the style of her story Eagle Street House.

There was a literal connection between the telephone lines and our game of telephone. It’s set against a black page as well and with the hole present it represents the museum/archival aspect of the project. Each time you see a series of black spreads, it is preceded by a hole in the ground—the book cover hole opens to the montage spreads, a hole in the grass to the short story, a hole in the concrete to a mythical underground museum exhibition, the mouth swallows you into the caverns. It was important to center that shape immediately so that when this happens throughout the book, the reader can have it in mind to read the holes with a multitude of meanings. The black and white version of this was another call to the game of telephone too—that the color shows up later and the details and understanding change with each viewing.

Feinstein: Can you talk a bit about your use of Edith Fikes' text / passages throughout?

Mantle: Edith wrote Eagle Street House specifically for the book and in response to the images. There had been a more explicit “Museum” section in earlier versions and I had wanted to commission a Curator’s text to discuss the “Museum of Misplaced Fortunes.” Edith’s name came up amongst a few people I mentioned this idea to. I approached her with a draft of the book and a massive folder of images and research materials and she ran with it. It was a lot to digest and pack into a short story.

She steered away from something more formal and academic sounding and instead wrote about an older woman who wishes that her modest home and belongings become a museum after her passing. A lot of the pieces archived in the museum show up in my photographs or are referenced in the titles listed in the Guide at the end of the book. It’s such a strange text—surreal, absurd, comedic, tragic—and relates back to the photographs and project in a way that I couldn’t have envisioned or fully planned for. My sequence changed slightly after Edith’s writing was finished to make the back and forth between the images and writing more complete.

The short passages throughout Misplaced Fortunes were excerpted from a book about treasure hunting by H Glenn Carson. I had mostly finished shooting for the project when I was at a flea market and came across this book. The project needed text and at the time I had been editing through a lot of different newspaper articles and historical texts that I had accumulated but nothing was working very well—the tone was off. Carson’s writing about treasure hunting is so open ended though. I started to read it as a sort of philosophy for life through treasure hunting. There were also a lot of direct connections I saw to photography and the approach I had going into this project—not expecting to find a treasure of any sort but continuing to look anyway. I focused on his passages that read as calls for curiosity and observation—small wisdoms in how to navigate a fraught landscape.

Feinstein: At what point did you envision this as a singular body of work? Do you make images and then pull them together into a larger idea and context later or did you have a long term vision and concept along the way, as you were making them?

Mantle: It was a singular body of work from the beginning. There’s a lot of overlap in my work and other projects I took on concurrently factored in conceptually at times. Even certain mages I made for other bodies of work ended up landing in Misplaced Fortunes.

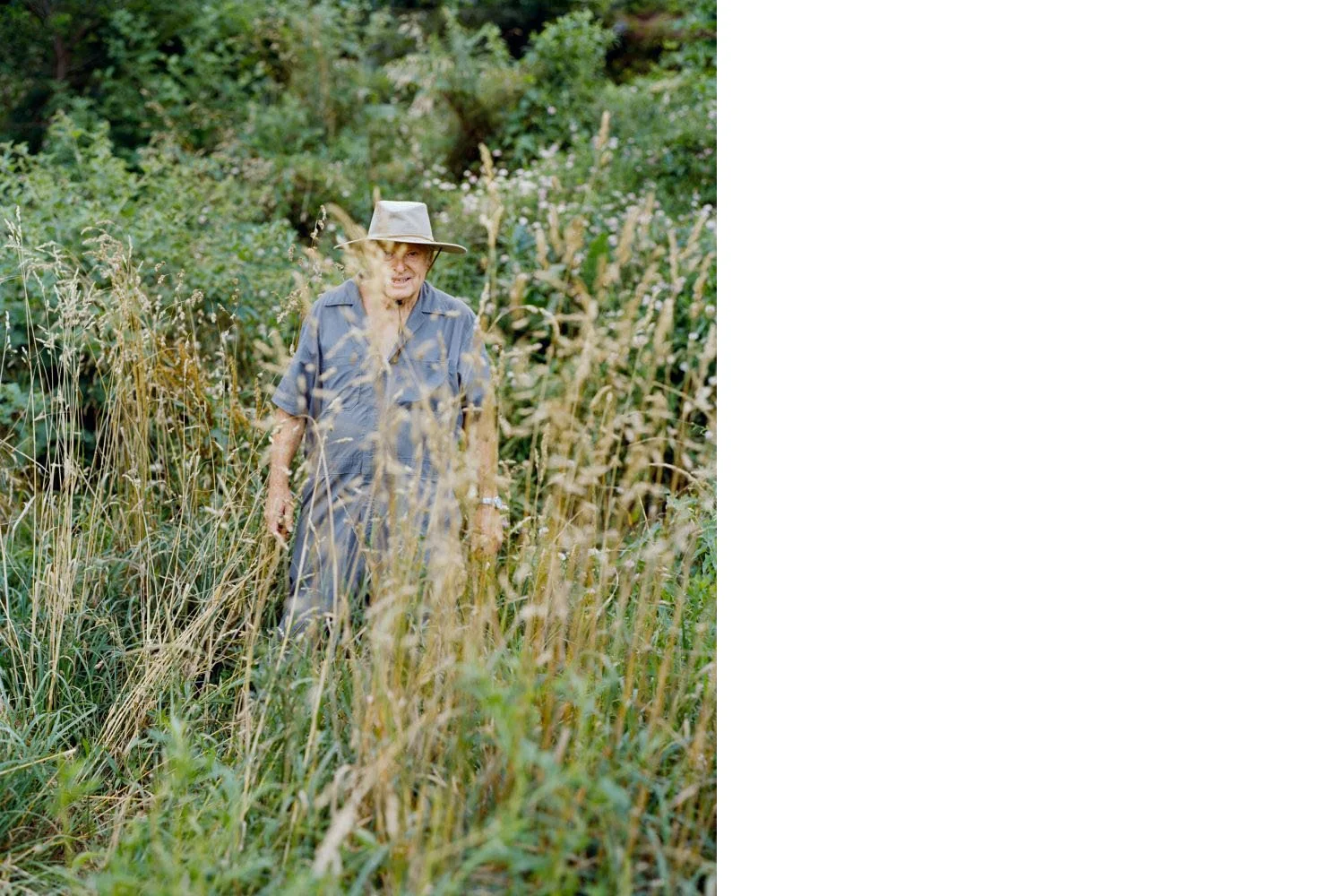

Going back to the start though, I had been on a commission in eastern Kentucky (Harlan County) and the story was so convoluted and hard to visualize that I started thinking about how to better discuss and photograph the region while staying within a documentary practice. A while after that I wanted to find a mythological figure or story in Appalachia that I could approach through documentary. Eventually I came across the story about Braddock’s lost gold and it had enough interesting pieces to start with and the narrative expanded as I continued—it led me to ideas about road building and years of industrialization/capitalism driven growth in the name of Progress and Manifest Destiny. All the themes and ideas kept connecting to and scrutinizing one another and in a personal, meta way back to photography too.

With this project I was doing a lot of research and planning before going on trips to photograph. I would try to make sure I was versed in what I wanted to look for, had a plan for where I was going, and could sort of leave all of that to my subconscious and then go out and work intuitively and find photographs to make along the way.

© Ross Mantle

© Ross Mantle

Feinstein: The mystery throughout makes me want to know more about you, your background, and where you are in all of this. Where does your own personal/cultural history play into these images and ideas?

Mantle: I’m from Pittsburgh, my family hasn’t lived anywhere else since getting here about a century ago. Some relatives have moved away, but most are still in the region. My personal and familial history is maybe what you would expect of someone from the region—there have been ties to mining and steel and industry. Stemming from these histories and the multitude of other histories in this region in which internal and external powers exploit the people living here, I think a lot of people from this region have an embedded skepticism of any authority or form of power. This is part of who I am too—that sort of wry skepticism comes through in this work and the ways I’m looking at the landscape here.

© Ross Mantle

Feinstein: There’s also a kind of indirect humor to it, right?

Mantle: Humor and curiosity are important to me—it’s not always explicit, but these approaches are always present. Many people have looked at my work and commented on how sad it is or that it seems nostalgic—I can understand seeing some photos that way but I think those readings are incomplete projections. Clearly defined approaches that adhere to the edges of definitions—in any area of life—are not exciting to me. Pittsburgh exemplifies this to me as a city. It’s a bizarre mess of buildings hidden on steep hillsides and along convoluted streets built as needed and with seemingly little regard to future planning. There are a lot of issues here, but I love the way the city and region.

It’s a place that’s grown out of necessity in a very makeshift way. It’s not one that has been intricately designed and planned. I think a lot of this is reflected in the people who are from here or have been here long enough to adapt to the pace of the region. It’s a funny, sort of magical place that is dull and gray most of the time. It’s perfectly mediocre and incredibly beautiful. I love it here. There are a lot of disparities that don’t necessarily add up to anything great, but they can simultaneously be deeply funny and sad, making it an interesting, complicated place.