© Sarah Rice

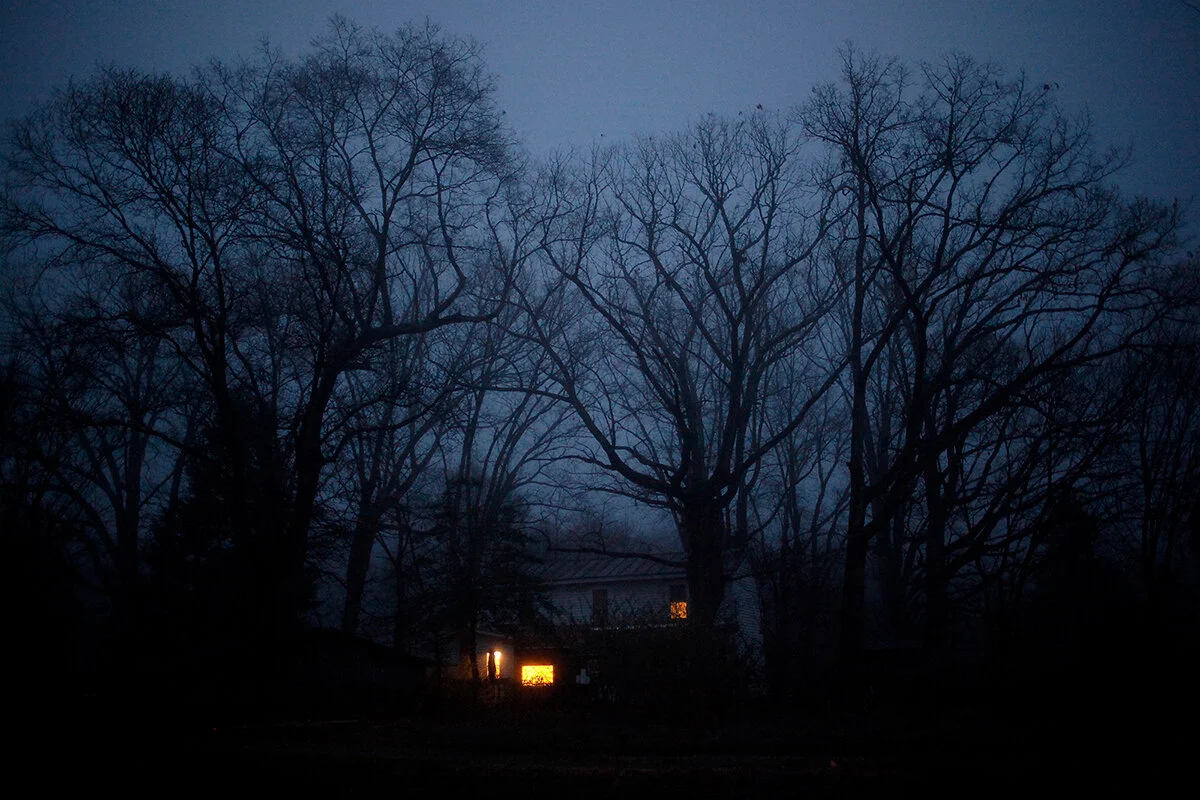

Sarah Rice documents an anarchist quest for equality within a rural Virginia commune.

[…] what we needis here. And we pray, notfor new earth or heaven, but to bequiet in heart, and in eye,clear. What we need is here.

- Excerpt from The Wild Geese from The Selected Poems of Wendell Berry

Tucked away on 72 acres of farm and forest, a commune in the hills of Virginia has been practicing its own form of social distancing for more than a quarter century. Documentary photographer, Sarah Rice, has made a regular pilgrimage to this cloistered community for nearly a decade while nurturing and expanding a raw and intimate collection of photographs. Her ongoing project, What We Need is Here, is wild and decidedly unromantic.

Rice picked me up in her Volkswagen on a drizzly summer morning at the Portland, Maine bus terminal. We discussed meeting over Skype or taking an interview by phone, but making this personal connection seemed important. I would love to regale you with some of the stories from her life which we chatted about over huevos rancheros and coffee—she’s the former drummer of a Mexican band, the survivor of a near-death motorcycle crash along the coast of California, and has had three face-offs with various incarnations Pepe, the brain tumor—but, alas, the audio recording of our interview is barely decipherable through a cacophony of glass dishes clinking behind the bar and diners chatting fondly and fiercely over scrambled eggs and mimosas.

After the disheartening playback when I realized this, we exchanged written messages back and forth, including the interview you’re about to read below. Pepita (Pepe’s smaller grandchild) put a hamper on things and then the timing wasn’t quite right for wrapping this up from my end. And now here we all are, isolated within our own homes, forging new forms of community and, perhaps some of us, starting to question if the world we knew before is the same world we want to return to. I’ve realized now is the time to come back to this story and share with you a glimpse into Rice’s work and the experience of immersing herself, in the most human of ways, into what this community of roughly thirty people describes as “an anarchist, egalitarian, non-coercive, non-hierarchical, consensus-based, income-sharing, sustainable, consent-based culture.”

Amy Parrish in conversation with Sarah Rice

© Sarah Rice

Amy Parrish: How does this story begin?

Sarah Rice: This project started while I was in Virginia for a week or two searching for something to shoot while I was there. I had long been interested in exploring the idea of community - what makes a community, how are they created, and especially what drives people to leave one community to seclude themselves in another. I had been photographing cloistered nuns. When I heard there was a large commune in Virginia, I immediately thought of the nuns, and wondered if there weren’t some similarities between the inhabitants of each of those spaces. Did they share a strong desire to surround yourself with like-minded people? I contacted this large commune and explained what I was interested in, and arranged to go visit.

After a few hours at the commune it was clear to me it wouldn’t work as a photography exploration - their rules meant I had to have a minder with me at all times, which doesn’t work with the way I work - so when they asked if I’d be back I explained why I wouldn’t. The woman assigned to guide me around listened, and told me if I was looking for a looser, freer space, I should check out a nearby commune where a partner of hers resided. She set it up, and the next day I visited this second, much smaller commune. It was a completely different experience - I was allowed to wander freely and ask questions of whomever I encountered.

Most people were willing to stop and talk to me and answer questions. Many were open to being photographed. I asked if I could continue to make photos for the time I was in Virginia, and they agreed. After just a week there I was making images unlike any I’d made anyplace else. I had planned on leaving town but rearranged my travel plans to stay longer and see what else I could make of this space. When I wound up leaving after a couple weeks, I was not intending to return. But after spending time with the images, I realized they were more about this specific space than the idea of community.

I wanted to explore what existed in that community that I hadn’t encountered at any others. And ultimately, I wound up spending years doing just that.

© Sarah Rice

© Sarah Rice

Parrish: Have there been any ethical dilemmas you faced while creating this work? Can you talk a bit about how trust, consent, anonymity, and other factors play into this project?

Rice: Consent plays a very important role in the way this commune is structured. It’s practiced and taught and respected and sought. When I’m working on a project, I always explain very clearly what I’m doing, and I don’t proceed or push if someone is not interested in being photographed. Respecting people is much more important to me. So that was my approach here as well, the only real difference being it took quite a while longer to gain the trust of a lot of the members than many other projects I’ve worked on. A general distrust withdrawing from society, and strong feelings of distrust unite a lot of the members. Someone from the outside coming in really needs to put the time in, which I was more than happy to do.

I kept returning, and bringing back prints each time to show everyone what I was making. I always respected any wish to not be photographed, and made sure I did whatever I could to make people comfortable in my presence. With some that meant simply putting the camera down whenever they entered a space I was in. Over the years they began to open up more, and I did as well. I started to share more of my life with them, which at that point felt both natural and a departure from how I’ve photographed in the past.

Now when I return there’s some who are such supporters of me and my work, and as always there are new faces I get to introduce myself to and start from ground zero.

© Sarah Rice

© Sarah Rice

Parrish: Does your personal story ever weave in with those within this community? You've faced death more than most. Has this affected your photography or the relationships with people living on the commune? In other words, does this rapport and exchange of experience work both ways, or do you try to keep your own narrative removed as a neutral observer?

Rice: My relationship to sickness and mortality has definitely affected my photography. It’s made me more open. I used to be a pretty private person, but I learned when I first started dealing with anything serious that once you talk about it, you find all the people around you who’ve been through something similar.

Being open helps people to not feel alone, and that’s a big part of how I work in the world. I’m happy to have long conversations about serious topics on the regular with people I’m photographing - conversations where I might make no, or few photos.

I went to photojournalism school so I think I came into photography with a kind of training that was very rigid in terms of how you interact. Now I feel very at home in the space I’ve carved out for myself, which is always as a human first, and photographer second. That doesn’t work for a lot of photographers but it is vital for me. I can stand behind all of the photos in this project and know I have the full consent and support of the people in them. Photography for me is a relationship, and respecting that is paramount.

My personal story doesn’t weave into the story these photographs are telling, I keep that separate, but it affects the way I interact in many ways. Some of the themes the work touches on resonate with my own life, and hopefully the lives of everyone else who gets to look at these images. I try to draw connections with my work: to map them, document them, and build them.

If my work leaves the viewer feeling connected to the people I’ve photographed, like there’s some understanding there or even similarities, that’s what I’m after.

© Sarah Rice

© Sarah Rice

Parrish: It was interesting to hear that your approach and preferences seem counter to so many other working photographers. You seem to photograph people with ease and I understand it’s those details without a literal human presence that are up next as you work towards completing a collection for book publication. How or why do you feel you connect so smoothly with people in such intimate situations?

Rice: I think I connect with people because I feel-- very strongly. In life in general. When I meet people I’m feeling where they’re at and who they are and responding to that at a very gut level. I have an endless appetite for and curiosity about people. My life and my work are centered on the human experience.

It is challenging to me to make photographs that don’t have people in them in a way that feels right to me. It’s a very specific note I have to strike, and more often than not I don’t. It might have something to do with the element of the imperfect, and chance, that I love. That’s harder for me to find when I’m not moving following something or someone that’s moving. It’s a challenge that I’m interested in though.

© Sarah Rice

© Sarah Rice

Parrish: Do you have any words of wisdom to pass along?

If you’re uncomfortable photographing people it helps to know why you’re there, and feel very strongly about whatever that reason is. Then articulate that to whomever you’re photographing. Remember that this experience is not about you. It’s about them - respecting them, making them comfortable, seeing them, honoring them. It’s quite a vulnerable position people place themselves in.

Focus on how they feel, not how you feel.

© Sarah Rice

Parrish: That’s really great advice. And what about your audience? If there’s one thing you hope that viewers would take away from this work, what would it be?

Rice: I hope people are able to walk away with a sense of respect for what it takes to create a life like these humans have created on these 72 acres in Virginia. I hope they can see past whatever romantic notions they have of commune life to the rawness and the realness that actually make up this existence. I hope viewers can feel connected, in some way, to this group of humans or the land they have made home.