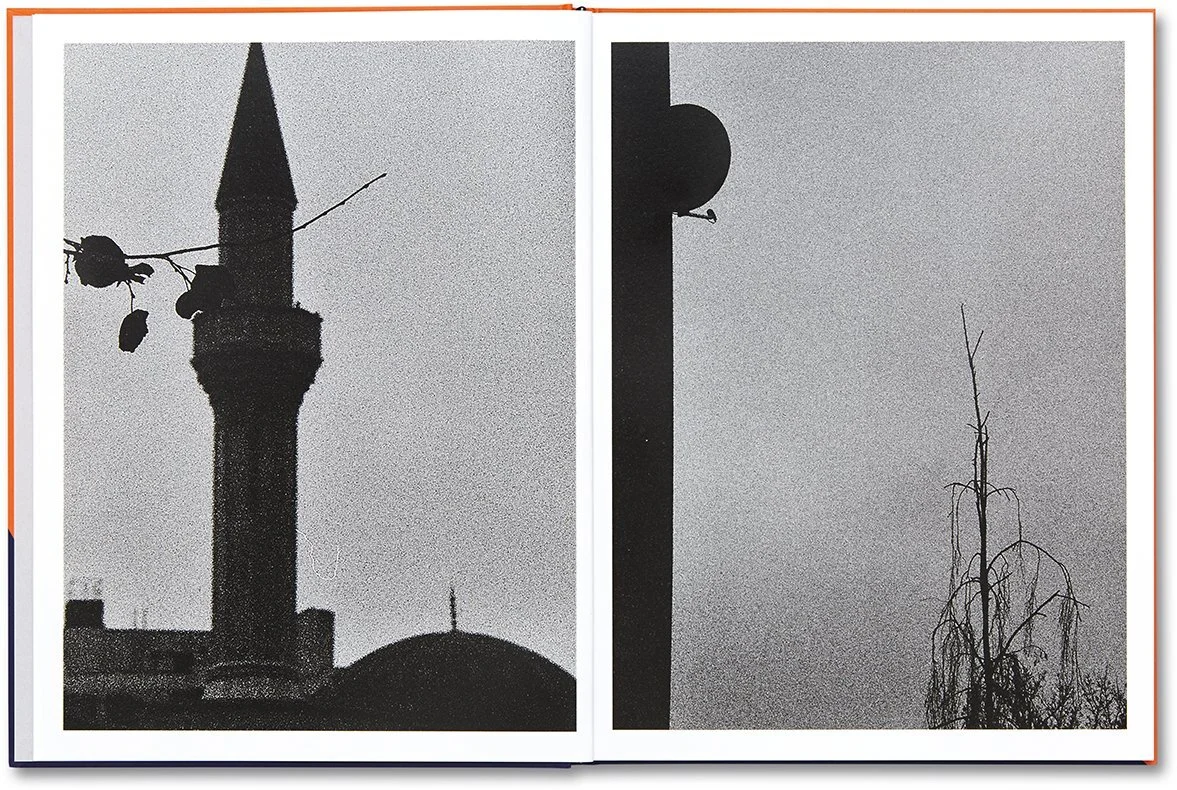

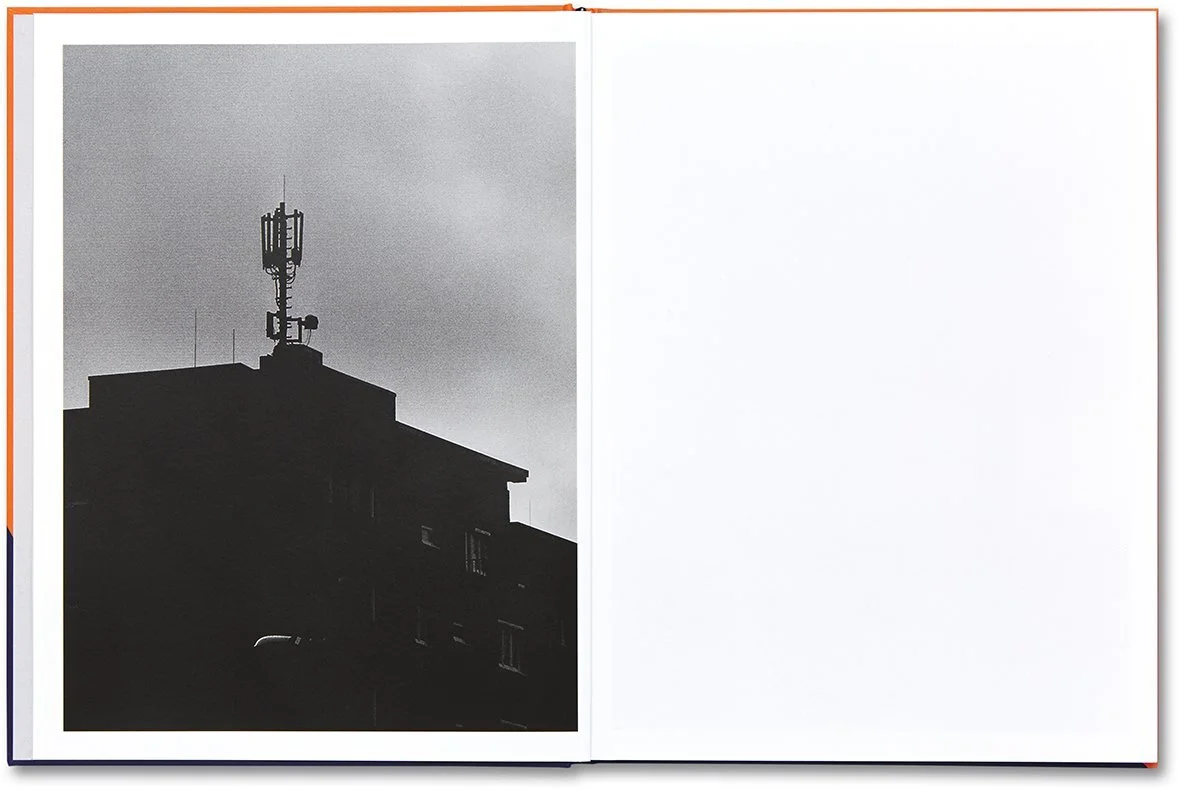

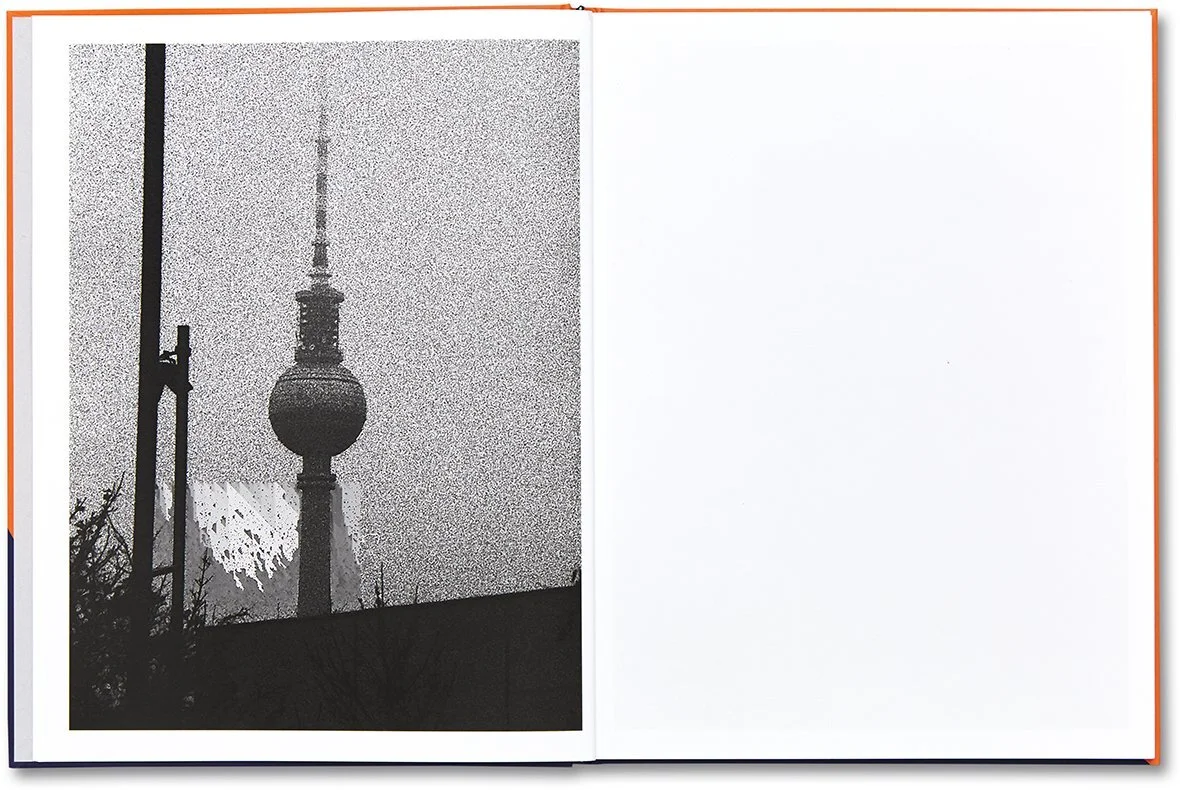

In 2017, Brad Feuehelm spent three days wandering around Berlin. He photographed various scattered symbols of capitalist modernity – billboards, television stations, satellite dishes, and contemporary office buildings – with no specific beginning or end in sight. And then he stopped.

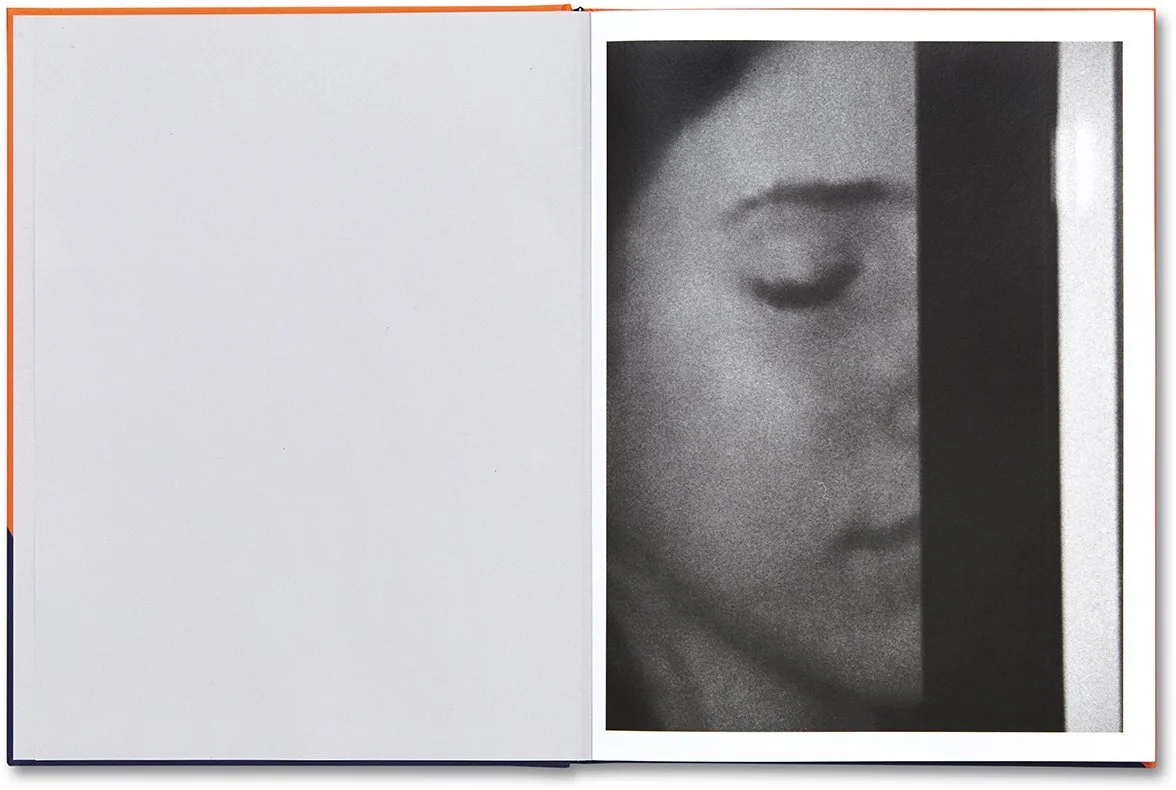

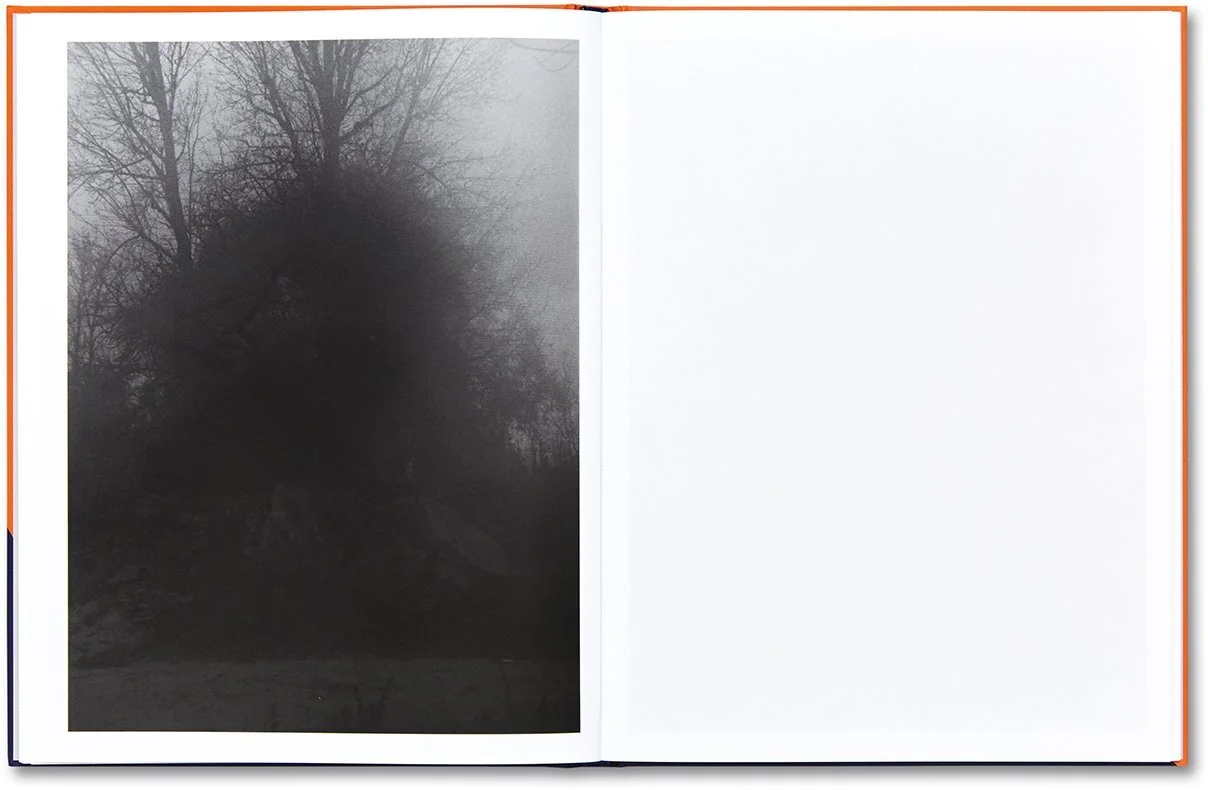

Rather than painting a linear narrative of the city, its people or cultures, Feuerhelm cropped, collated and reorganized these often blurry, grainy black and white photographs into Dein Kampf, his disorienting 2019 photobook published by MACK that emphasizes the equally disorienting, blurry and anxious ways we navigate history and political ideology.

For Feurhelm, whether it's on the left or right, nothing is clear, everything is broken and whichever direction we turn, we confront a mess of cacophonous gray.

Jon Feinstein in conversation with Brad Feuerhelm

Jon Feinstein: You mention, and I know this about you from your online presence and a few other interviews, that you are fascinated by ideology, its power, and its role in social context+historical construction. Can you tell me a bit about where this started/ what's driving this?

Brad Feuerhelm: As for ideology, my aim with Dein Kampf is to distance myself, through visual means, from the advanced decay of ideology and tribalism. My worry for the present is that we are embattled with each other with differing means at a fever pitch in which we believe that we have each other as a common enemy based on the nuances of belief. Divisions and sub-divisions and their harrowing call to violence (institutional, soft, and hard) from all sides of the political spectrum are clamoring for a position in the hierarchy of their ideals.

It feels very familiar if one is somewhat knowledgeable about 19th and particularly 20th Century conflict. As someone from a left background, I have seen an incredible amount of violence in speak, thought and action from people and groups that I had formerly associated with my own moral compass, politically. I think that was the start of how I began to re-examine my role within these paradigms, especially as an image-maker and collector of photographs.

Feinstein: In a recent interview with Paper Journal, you describe wanting to rethink images as a tool of ideology. Why specifically now?

Feuerhelm: My contention with images is that we have come to a point where the historicization of violence and propaganda have become so embedded in the western landscape that the only way to assume some locus of control for producing more images is to look backward, to see and divine some sort of common thread in which the markers of ideological shift may be re-examined and avoided. The first portal for my interest was to strip people from my frames.

I feel that with the cacophony of voices pleading for ideological representation through personal, identity and political means, that the best way to adjust from my own disambiguation was to remove the markers of the citizenry and their representations. I did not want to individuate their plight, nor add solidarity with “people”. It sounds misanthropic, but it’s rather a device in which using effigies or space of non-peopled locality, I could remove these issues, so I guess that is where appropriation comes in a bit and looking at the surplus of images.

Feinstein: You mention distancing yourself. Are you in this personally on any level?

Feuerhelm: I’m not and that is the point. I am attempting to disjoint myself from the patterns of abuse found in photographic images, by simply observing their fallacy throughout the landscape of Berlin-a city that has watched the cyclical results of differing tyrannies.

Feinstein: This may just be coming from my knowledge that you grew up going to punk and hardcore shows, but I'm wondering if that influences how you engage with images –– both the aesthetic and the complexity of ideology, which, in my experience growing up in the hardcore + anarcho-punk scene in NYC, was often a bit rigid.

Feuerhelm: For sure!!!! Music is my number one influence. I can use it to program feeling, vibe and use it as a preset to inform the way I shoot. The thank-you lists that are in my books usually (now) have a reference to the partial soundtrack from when I was shooting. This round it was The Sisters of Mercy, which was on repeat along with Swans etc.

I come from playing in bands for years and I listen to loads of Hardcore-lots of straight-edge and militant vegan 90s and 2000s material, like Earth Crisis, Snapcase (decidedly less militant), Strife, All Out War, Deadguy etc. and still listen to newer jams like Harm’s Way, Cult Leader, Converge, Judiciary, Advent etc. along with lots and lots of metal, hip-hop, and techno.

I was never straight-edge and playing in those bands always presented a challenge as I could not find a way to absorb the rules of conduct and yes, as you know personally and have aptly pointed out-those same rules often led to their own tyrannies-this is a good metaphor for how I see the extreme left at present-an idea that starts as morally profound or good but is then taken over by despot organizations and turned into a militant and abhorrent structure from which to perpetuate differing forms of violence.

Feinstein: I'm going to ask a pretty basic + obvious question, but bear with me. On the surface, the series in black and white could read as nostalgic or reflecting on the past, but I'm guessing it's more complicated - can you discuss?

Feuerhelm: No, this is a correct assertion and not basic at all and though I find monochrome easier to work with, the dissolve of the images-the grain and dissolute nature of film structure certainly asks the viewer to think through the era of production.

The synthesis of anachronisms are important for me in the work-they trigger false impressions of memories not my own. The way we interpret nostalgia however is read widely as giving precedent to favored memories in work-this for me is a limited way to look at it.

It is possible to have nostalgias built through trauma and I am interested in that space in which collective memory can examine say the Atomic American Drive-in as a space in which the conflation of enforced and encoded memory and nostalgia are purposefully thwarted towards uncomfortable propaganda based on something fearfully nostalgic at its base, but exemplified in nostalgias of progress.

Feinstein: I understand that you made all of the images for the book within three days. In my mind, that compression seems to reflect your ideas about the blurriness of history and its representations. Can you talk about this process? Were you initially thinking of this as a book?

Feuerhelm: I tend to work this way. I find the compression and intensity of limitations extremely helpful. Let’s call it “method photography”- (joking.) I want that space in which I can force myself into a certain way of thinking about the work and the images and it gives me less space to repeat and produces, though frenetically, an atmosphere or condition within the images, I believe that register the claustrophobia that interests me. I think this frantic almost trance-like state works best for me.

I have only two longer-term projects unfolding and I am convinced one of those ended after 1.5 years and the other is on year two. I knew when I got the images back that it could be a book, but that’s how I think. I do not think outside of two covers. The whole of Dein Kampf as a brick from cover to cover perfectly illustrates the intention I had. I am very happy with it and feel the topic and the innuendos are given space. There are some symbolic flows in the book that need a bit of unlocking, but I am fine with that.

Feinstein: You grew up in the United States and now call Slovakia home. I think about this work in the context of you flowing through a new landscape (Berlin). One that's charged with a complex history, one that's on some level foreign, murky, daunting, unknown. How much of this holds true to your experience making this work and processing the history that lays behind it?

Feuerhelm: I do have an affinity for Germany, its people and its photography books in particular-even ones made by Americans like Michael Ashkin, John Gossage and Mike Slack among others. The condition of the post-war visual economy offers, like documentary photography in Britain a range of philosophical possibilities that I find tempting to say the least.

With Germany and Berlin in particular, you have so much nuance that borders on psychosis that it’s hard not to be infatuated by it. This is of course not to belittle German suffering, but at the end of it, anyone with some bit of historical contextualization still comes up with “wtf”.