© Eirik Johnson

Photographic typologies can be boring. Serialized to death. A bit too literal or on the nose. (I say this as someone who still loves them, in spite of agreeing with Joerg Colberg’s New Year’s plea to photographers a decade or so ago to "stop making typologies," at least for a while, still can’t get enough of them.) So, when a photographer adds some warmth, digs deeper into the soul of a structure, I want to learn more.

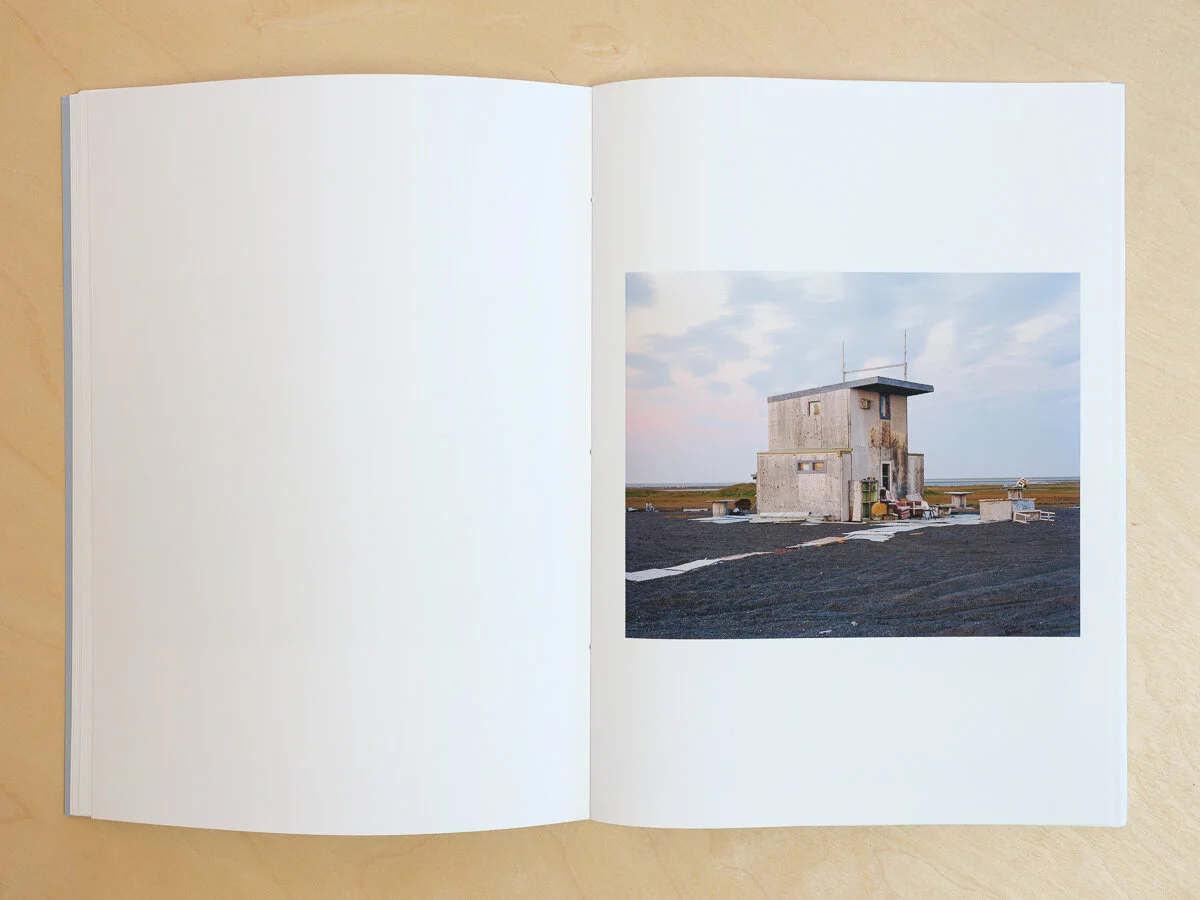

Enter Eirik Johnson, who, since 2010, has been making typologies of seasonal hunting cabins built by the Iñupiat inhabitants of Utqiaġvik (formerly known as Barrow), Alaska through the extremes of the Arctic summer and winter, which culminate in his new book Barrow Cabins, recently published by Ice Fog Press. The cabins rest on the shores of the Chukchi Sea, part of the larger Arctic Ocean, and are built from a variety of makeshift materials – weathered plywood to old shipping pallets collected from the nearby-decommissioned U.S. Navy Base – whatever is on hand.

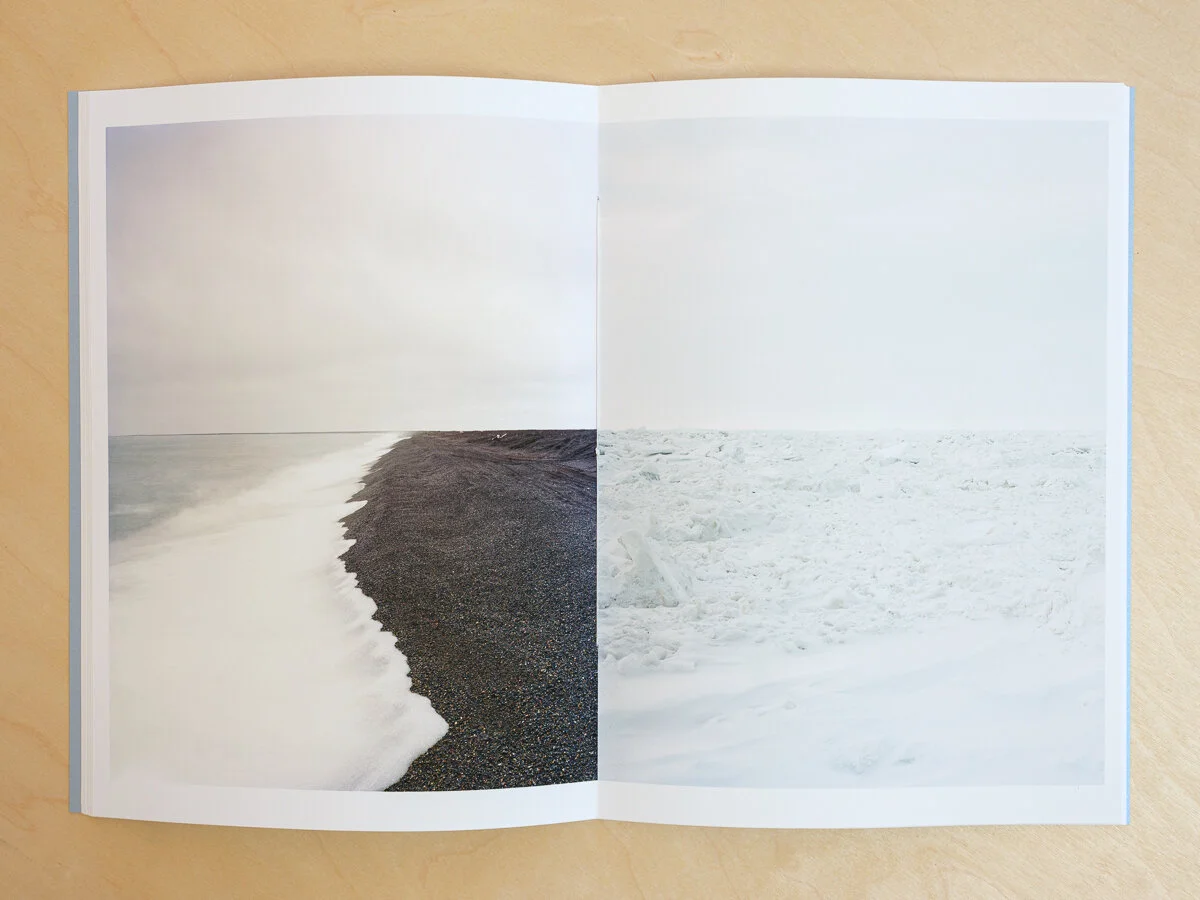

Rather than comparing structures purely for their architecture or photographing them under a monotonous, non-descript sky, Johnson’s point of comparison is the light and temperature itself. He describes it as a “meditation on the passage of time.” While on the surface, these photographs might appear to focus on the structures, they feel more like explorations of the emotional capacity of weather, seasons, and the metaphoric hunt for light and calm.

I spoke with Johnson earlier this month as he was preparing for the book’s release. BTW, you should get a copy.

© Eirik Johnson

© Eirik Johnson

Jon Feinstein: How did the series start? What first drew you to photograph the Barrow Cabins?

Eirik Johnson: I first traveled to Barrow, which is now officially called Utqiaġvik, on assignment to photograph scientists monitoring chemical plumes beneath the tundra, a legacy of the decommissioned US Navy Base outside of town. By day I would photograph the scientists, but during the late light of the Arctic summer, I would photograph on my own. That’s when I first encountered the cabins. I’ve had a long fascination for makeshift architecture, having photographed commercial mushroom foraging encampments and other strange structures in the past. That’s what drew me to the cabins. Each one was unique, fashioned out of found and salvaged materials, some quite humble in design and others more ambitious. In a sense, they reminded me of portraits of their makers.

© Eirik Johnson

© Eirik Johnson

Feinstein: You mention it a bit in your statement but can you elaborate on the history and tribal significance, of the barrow cabins?

Johnson: The cabins are essentially a seasonal hunting camp situated strategically near Point Barrow between a lagoon and the open Chukchi Sea, part of the larger Arctic Ocean. This location has historically been a place where the Iñupiat would camp for extended periods of time to hunt and fish. Now, the Iñupiat inhabitants of Utqiaġvik spend weekends or weeks in the cabins hunting for migrating waterfowl or seals, while kids play on the swings and max ramps that they’ve built at each cabin.

Feinstein: You photographed the cabins in two different seasons - the extremes of winter and summer....can you expand a bit for me on the metaphors and meditations on time, the horizon, seasonal extremes, etc?

Johnson; Following my first visit to photograph the cabins during the summer, I kept pondering the way time had felt “stretched out” while I was working, as I would watch the sun skip along the horizon of the Arctic Ocean between midnight and early morning before it would begin its gradual climb back into the sky. That sort of extreme made me reflect on the nature of long-term thinking, far removed from the bean-counting of our typical daily routines.

That in turn, sparked my interest in returning during the opposing seasonal extreme, the Arctic winter, when the sea ice has completely blanketed the lagoon and sea and the sun only rises enough to cast a brief window of subtle light upon the landscape before disappearing again. When I did return, it was nearly a year and a half later, so not only was I encountering an extreme seasonal shift but also the longer passage of time and the changes to the cabins that brought.

© Eirik Johnson

© Eirik Johnson

Feinstein: On the surface, these are typologies. You're literally making the same shot in different seasons, and there is a sense of visual comparison in each. But when I look at these pictures, I feel more nuance and poetry than in some of the classic, photo-history-canon typologists (no dis to the Bechers, who I obviously love).

Johnson: While the comparison of cabins is the obvious subject of the work, no less important to me is the comparison of light and color that was apparent in both of the extreme seasons. It afforded the most beautiful pallet with which to work. I was also drawn to details I would constantly encounter among the cabins that reminded me of the improvised nature of childhood play. A basketball hoop or BMX ramp, but even the cabins themselves which reminded me of the treehouse my father had built for us as kids.

Feinstein: There are no people in any of these photos, just evidence of humans, their imprint, behaviors and transitory spaces. What was your interaction with the people who built these hunting cabins? Did making these pictures change your perceptions of them, of hunting, etc? Do you think it changed their perceptions of you as a photographer?

Johnson: Most of the cabins weren’t in use when I visited, although I did connect with several hunters spending time during the summer hunting ducks from the camps. I’m certain that if the camp was buzzing with activity when I visited, it would have colored the way I engaged photographically. That said, much of my work is concerned with traces of a presence, with what’s left behind, so that absence was what very much drew me to the cabins initially.

© Eirik Johnson

© Eirik Johnson

Feinstein: This isn’t particularly “new” work for you. What made it time to publish in book form?

Johnson: I really like the idea of letting things percolate over time. This work was done a number of years ago and I have since had the opportunity to exhibit the photographs in various formats, but I hadn’t felt ready to approach it in book form yet. That changed however when Ben from Ice Fog Press contacted me. He brought a very sophisticated approach to thinking about the work as a book. Neither of us were interested in simply re-creating the work as it had been shown in exhibition form. Rather we thought the book could offer a new lens through which to look at the work.

© Eirik Johnson

© Eirik Johnson

Feinstein: Beyond the obvious or literal connection (Ice Fog, Alaskan publisher, etc) why was it so important for Ice Fog Press to publish?

Johnson: There’s a shared sensibility among the previous titles that Ice Fog Press has published (elegant design and a deference to the pictures) and the Barrow Cabins work, which gave me confidence that it was a good fit. Ben’s interest in approaching the work as an artist book was very important as well and I was excited by the ideas he shared for how he saw the book taking form. While the development of the project percolated quite gradually, we really worked well together often finishing each other’s sentences so to speak. It was quite important to me as well that Ice Fog Press is located in Juneau, Alaska and that its focus is on work based in the North.