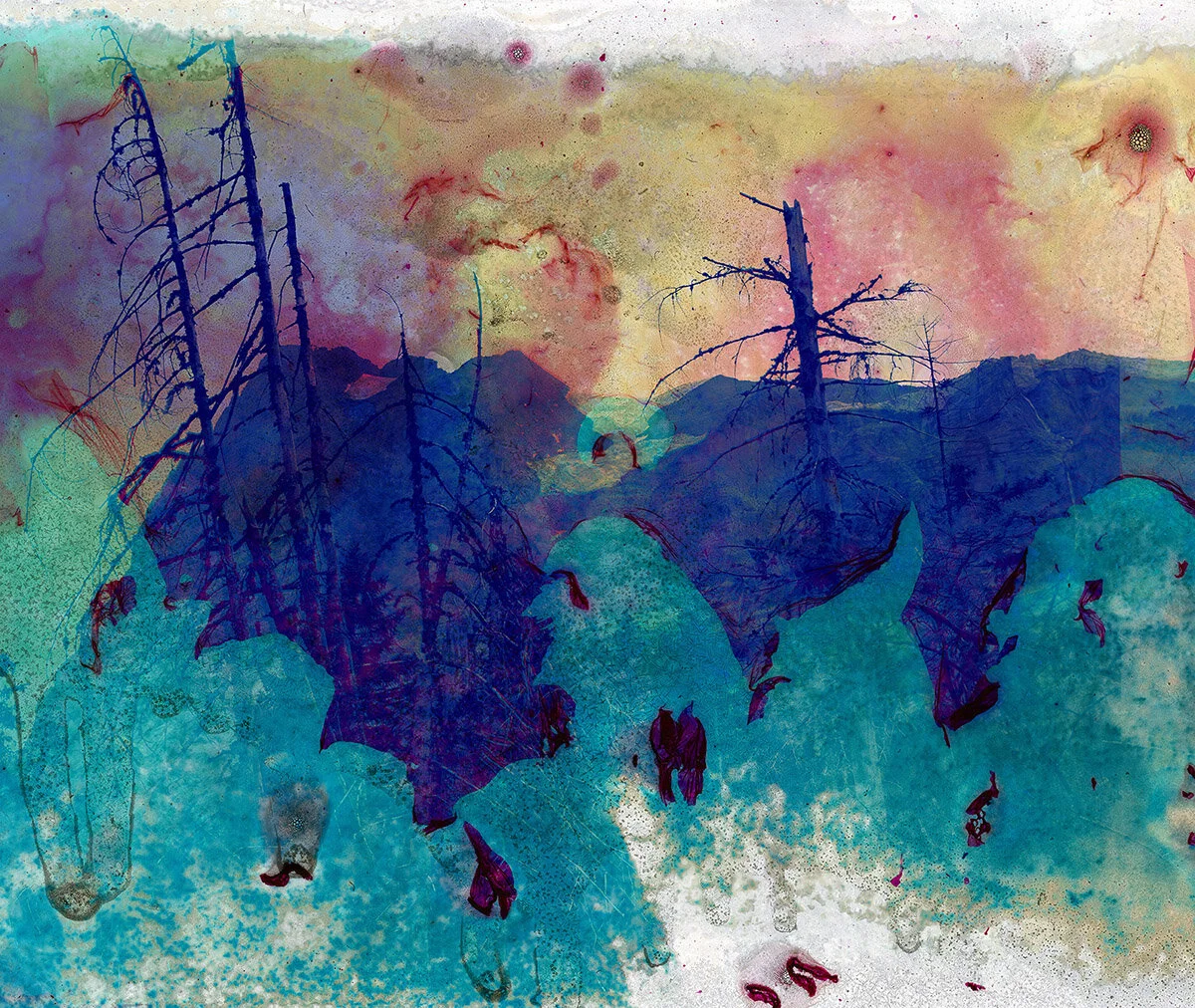

Anthem Number 12 © Doug Fogelson

Anthem, the latest installment of Doug Fogelson’s series Chemical Alterations uses chemically altered photographs of nature to comment on climate change and the destruction of the earth.

For the past few years, Chicago-based photographer Doug Fogelson has been making heavily saturated, almost-hallucinogenic images that respond to the peril of climate change. He photographs biologically diverse landscapes on analog film and subjects the negatives to industrial chemicals that make them morph, bleed and drip. The final prints retain varying degrees of the original nature scenes. In some, leafless trees battle the magenta and cyan-hued skies caused by Fogelson’s chemical burns. In others, abstraction takes over and no signs of the original scene remain. Fogelson asks viewers to do more than just marvel at technical tricks but to think carefully about their relationship to a quickly burning earth. While beautiful and inviting, they parallel the violence of human impact on the natural world and the Trump Administration’s erasure of policies that might help slow it down.

After his recent exhibition at Brooklyn, New York’s KlompChing Gallery, I spoke with Fogelson to learn more about his process and ideas.

Jon Feinstein in conversation with Doug Fogelson

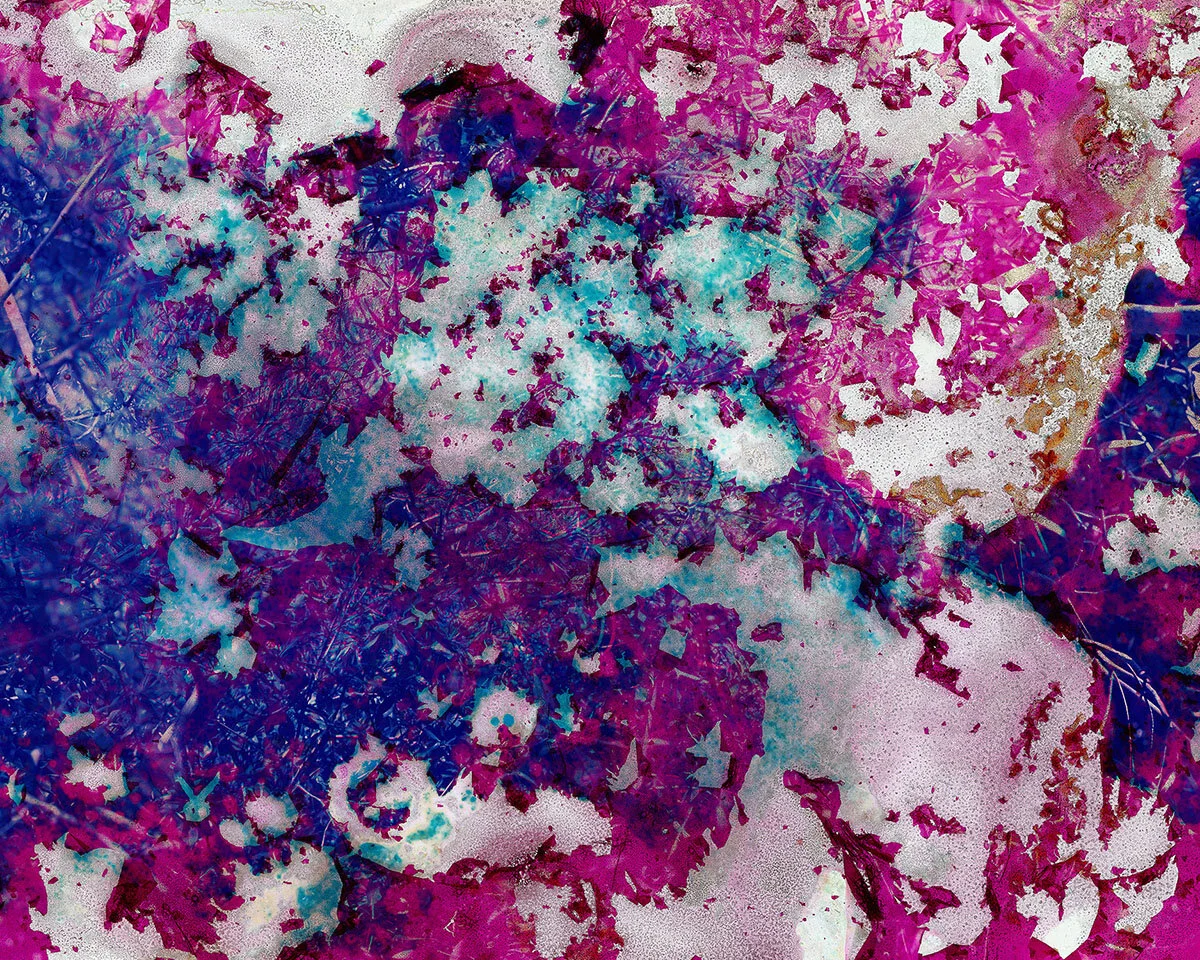

Anthem Number 13 © Doug Fogelson

Jon Feinstein: I started getting into your work when we included an image of yours in Humble's New Psychedelics online show in 2018. Specifically your ability to take process, experimentation and give it a kind of spiritual magic eye and tackle ideas deeper than the wow-y physicality of the image.

Doug Fogelson: In this time of extreme change and extinction it is important to find some ways to connect with forces larger than ourselves. The abstraction that comes out of my alteration of landscape images can signify concepts like the void, temporality, loss, and death.

So I marinate on that a lot as the full-color images disappear and re-create themselves anew. These processes also point to things very large and very small, for instance a photograph of a mountain is altered on the piece of film so that tiny micro "events" happen on the material’s surface, which gets high resolution scanned and I can zoom-in to inspect all the physical bits onscreen, it can feel like a connection with something cosmic. A Powers of 10 kind of thing.

Anthem Number 6. © Doug Fogelson

Feinstein: How does spirituality play into it for you specifically?

Fogelson: In short, I’m usually feeling very spiritual and simultaneously not religious at all.

There is a level of spirituality in my work mostly because I use or collaborate with the element of chance (over various projects). What is this force called Chance anyway? Is it truly random? In the chemically altered process photo materials actually grow into crystals, fractals, or stains as things dry/evaporate. That weirdly gives me some converse feelings of hope when the image falls apart and then regenerates in ways beyond an artist’s control. The final images speak to me about levels of natural resilience over spans of geologic time (think lichens hanging on to exposed rocks, which evolve to become lush jungles, that then become the base formation for a layer of crude oil– which is just originally compressed ancient organic matter underground for eons, that becomes the plastic of today).

In the process of making multiple exposure color photograms or other multiple exposure images, I do not know what the outcome will be until my analog film is processed. Exposures happen in the total darkness of the camera or darkroom. So the source materials used to make a photogram will either express themselves (their inherent qualities) more when multiplied or they can transmogrify/insinuate/refer to something else entirely even as flattened out forms. Less so with the in-camera multiple exposures but this leads me to consider how we see, what the brain does to make sense of stereo images, and how our lizard brains can relate to a jumble of overlapping scenes. Such abstraction feels closer to Cubism or Futurism, both of which I relate to as prismatically spiritual in nature.

Anthem Number 9. © Doug Fogelson

Feinstein: Tell me about the title “Anthem.”

Fogelson: The title is directly related to my disgust with the United States of America on the issues around Climate Change. I have been focused in this area for years, trying to make sense of the insane scale of the problem while living in the ass-backward land of climate deniers. I recently asked a Republican how he felt about it and got the answer, "ice melts"... Sure some of our citizens are well-versed on what matters or even helping to solve problems but many people still don't really care or even see the situation. We are just failing ourselves. This is happening while other countries manage to close coal power plants, ban single-use plastics, plant millions of trees, etc., etc, in real attempts at staving off the inevitable.

I won't even mention the extinction/murder of non-human life forms supercharged by the current administration (or is it de-administration?) and all those of the past who have sold our collective souls to the fossil fuel and related industries. Degradation is our actual anthem, our inheritance and legacy, this is the stupid song "we" all really sing through tacit participation and business as usual–so we should see it and own it (and stop it). My works aim to visually reflect that huge shift and also the multifarious legacy of our besieged and degraded global landscape is experiencing today. Americans still use and discard more resources than most of the planet combined, so to me this is an anthem for the earth that we know today. Tomorrow’s earth will reconstitute itself and life will go on regardless.

Installation photos from Fogelson’s recent exhibition at KlompChing Gallery

Feinstein: Building on that and your ideas about the environment, and your process of using chemicals to burn alter, etc images, Can you tell me a bit about your balance of process vs. concept? The sense of "burning" threaded through these images is so poignant right now...

Fogelson: My initial desire was to reflect human impacts occurring across various landscapes. Chemical Alterations came out of a whole range of experiments to affect the medium in physical ways over time. Sometimes I would leave images outside on the ground (face up and face down) for months, or drill holes in cameras and run film through them, soak images in various liquids, and the like. It turns out I’m not really that "into" the straight photographic moment as tableaux unless it is truly an image that resonates– most photographs just don't hold me captive long enough. Great works stimulate both the senses and the mind; straight photography can be quite a psychological adventure and less sensorial. I suppose sentimentality and attraction comes to each of us through different channels.

Feinstein: A little off-topic, but I learned recently that Andrew Bird played your wedding. I’m always thinking about how music ties into visual artists’ work and wonder if you see any parallels - clearly he’s influential to you personally.

Fogelson: Parallels could be drawn between some of the Bird music and my work I suppose, but only because of feelings of longing perhaps and because his brainy poetry and melancholy sounds bode well for any apocalyptic matters

Anthem Number 1 © Doug Fogelson

Feinstein: And the burning parallels?

Fogelson: Yes. Back to the apocalypse! Burning or drowning can be associated with the altered imagery from the Chemical Alterations, as can exploding, decaying, melting, boiling, scabbing... the colors come from the layers in the film emulsion cyan, magenta, and yellow (I use positive film). The cyan is a sort of underwater hue, maybe you can associate flooding, acidification or sea-level rise with this? The magenta can look like fire especially when it is degrading and flaking apart. These colors are even more vivid when wet during the alteration and then dry down to a slightly muted and rather crusty topography on top of the film base. The whole thing is toxic as hell to deal with.

Certain viewers see many of the final images only as beautiful landscapes, which is something I enjoy too, there is a kind of Zen in the ephemerality of it all.

Anthem Number 5 © Doug Fogelson

Feinstein: Where did you shoot the "raw material" of these images / the locations/ how does that tie into this work?

Fogelson: A big part of the fun here is to go out and do "bucket list" trips to amazing places. I relish in chances to leave my hometown of Chicago, where I work in an industrial warehouse zone, and visit locations with oceans, mountains, deserts, and other topographies. When heading out there like any typical tourist or traveler I see the usual attractions, but I always try to go a few steps off the beaten path and find my own way into a landscape or culture. It is important to bear witness and experience the life forms we have here today.

And despite what I said earlier about straight photography I have studied it and participated in various forms of photography starting in the late 1980s, so there is an accumulated visual literacy that I use to inform the images I make in the field. The language of historical landscape imagery mixes in my mind with more contemporary modes as I see a space and then view it through the rectangle of the viewfinder. But more importantly what I am listening to are subtle inner and outer forces, such as my mindset or emotions, the conditions of light and weather, and the non-human elements themselves (plant, land or water features), in the brief moments when visiting a place.

ANthem Number 8 © Doug Fogelson

Fogelson (continued): As I travel to these spaces I am so aware of the cliché' of all the tourists photographing the exact same thing on their phones or whatever. The spectacle is interesting sometimes, even as I always try to avoid having humans in the images and find a little piece of that same over documented subject to bring back on the film. The carbon footprint and societal impact of tourism is something I own as part of the process here in our Anthropocene or Capitalocene epoch. Flights will happen if I choose to go or not, the hotels will operate, etc...

Some of the places I go are part of my day job business or art residencies, some family travels, or simply to go out and make photographs of a specific region. I've been to Asia, Europe, Latin/Central America, Jamaica, Iceland, Norway, Hawaii, etc... over the years. Recent works are culled from lands with volcanic upheavals, mountains, and interesting water features. I'm drawn to dramatic landscapes but then sometimes make quiet pictures when actually there. Guess it just depends. Sometimes it feels I am making the same basic types of images no matter where I go.

Anthem Number 4 © Doug Fogelson

Feinstein: The Brooklyn Rail made a great point/ connection between your work and early landscape photographers. Do you see a parallel to today's generation of photographers riffing on/ deconstructing the classics? I'm thinking specifically of photographers like Cody Cobb, Teri Loewenthal, Christopher Rodriguez, and others...

Fogelson: Yes and no. I feel some connection with Loewenthall on multiplicity and color, other connections with Cobb or Rodriguez in the first stage of shooting out in the landscape before the alteration stage back in the studio. However, I find a bunch of contemporary landscape to be redundant in the age of digital ubiquity. Maybe it's because I am in midlife but I think an image should help you get "someplace" each time you look at it. It's a strange time when images are really fluid, functioning as reminders of things IRL but not quite documents and not quite conceptual art either.

The contemporary photographers I feel the most kinship with are Klea McKenna, Jeremy Bolen, Meghann Ripenhoff, John Chiara, Matthew Brandt, Susan Derges, Sam Falls, Mariah Robertson, Bryan Graf, Doug and Mike Starn, and lot's of others whose names don't quickly come to mind. Any of those who touch the medium in interesting ways (Welling! Jaar! The Institute of Design!) past or present are my faves. It's all good to deconstruct or riff on the classics so long as you're pushing the cannon forward, and hopefully, it becomes relevant to those living and working today.