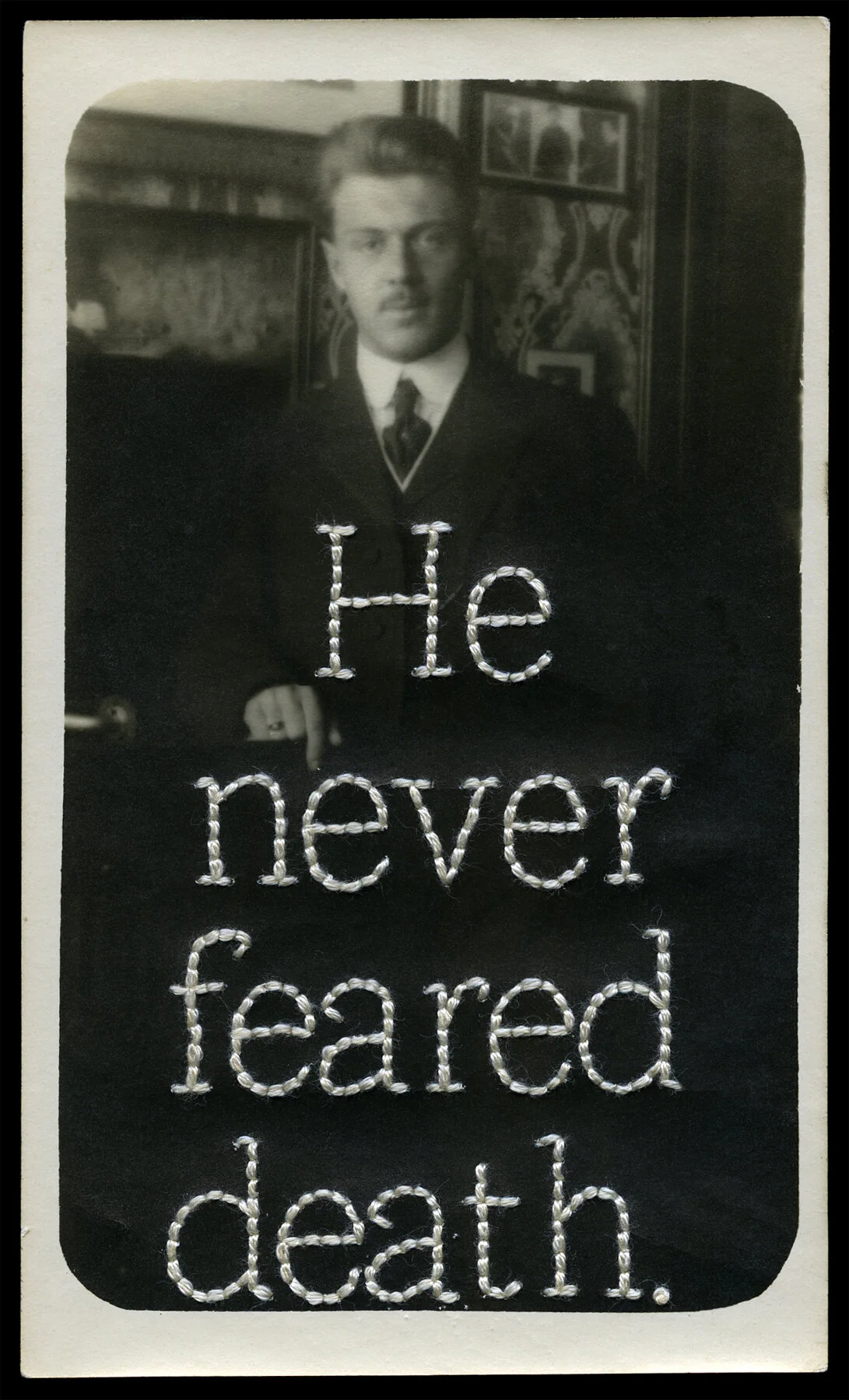

© Jane Deschner. From the series Remember Me.

For nearly twenty years, Jane Waggoner Deschner has been accumulating found vernacular photographic snapshots and studio portraits – her archive now exceeds 65,000 – and manipulating them to change how we understand their meaning and imagined histories.

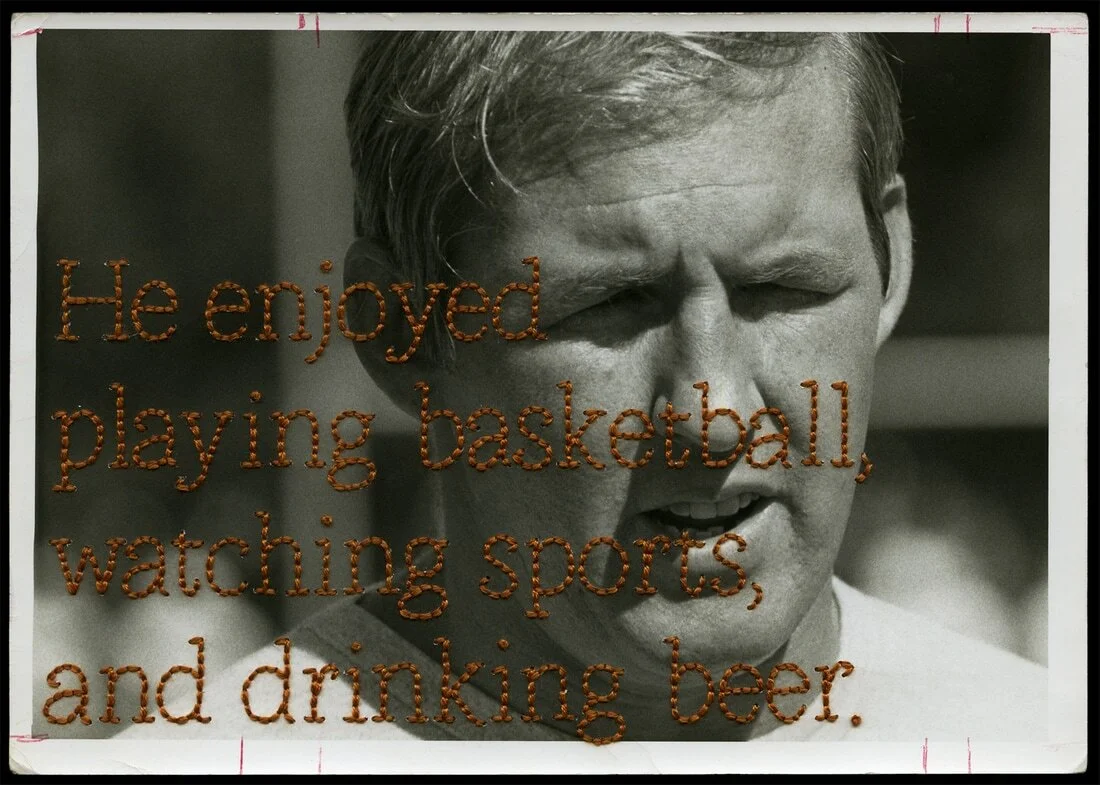

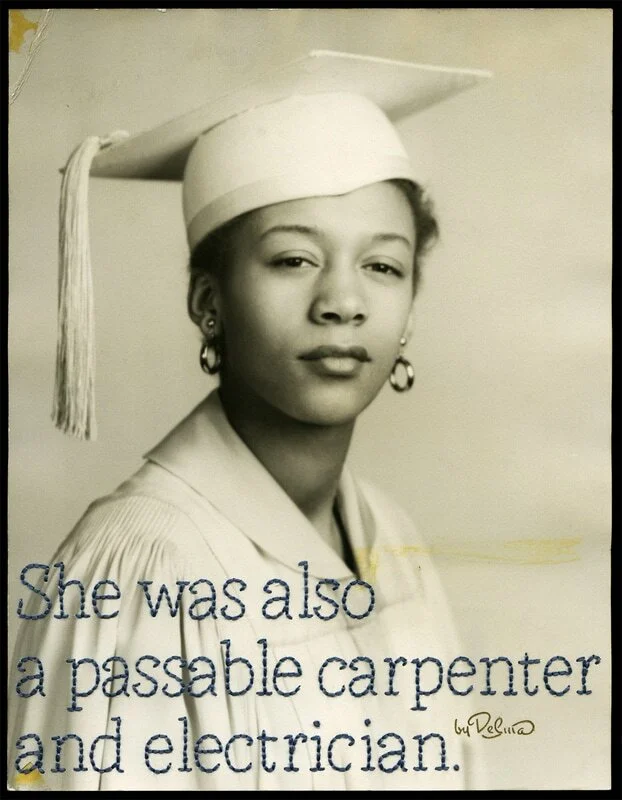

Deschner’s techniques range from digital manipulation to painstaking hand embroidery, often stitching famous, dry or ironic quotes to create what she describes as a “satisfying, meditative intimacy with mechanically captured moments of unknown people’s lives.” Her collages and embroidery range from personal explorations and existential ruminations on death to political commentary and discussions of gender.

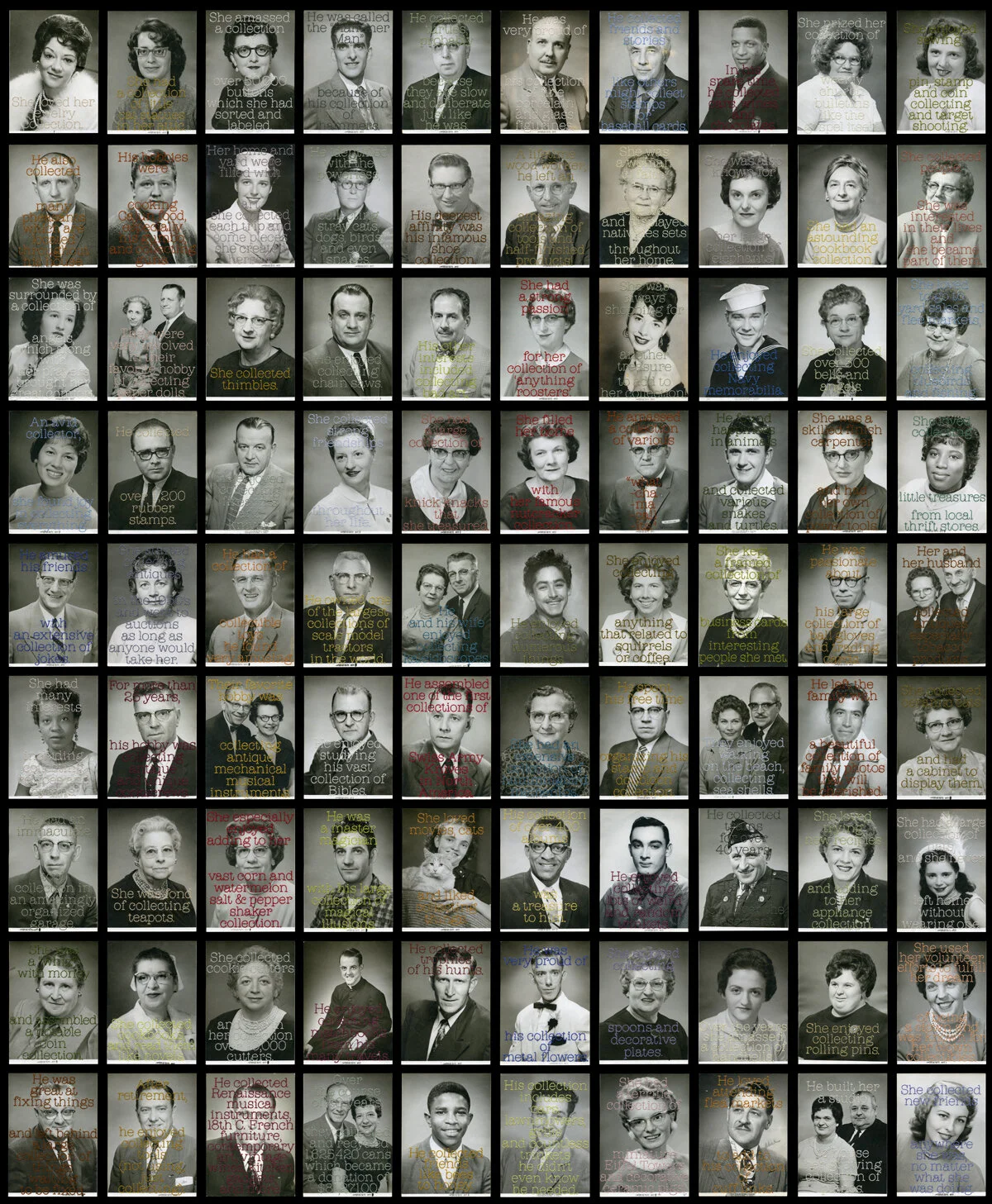

Her latest series, Remember me: a Collective Narrative in Found Words and Photographs, includes 700 found photographs embroidered with anecdotes culled from family and friend-written obituaries. For Deschner, this process illustrates a collective narrative that reminds us of how we are all connected.

Longtime fans of her work, we invited snapshot-collector-extraordinaire Robert E. Jackson to speak with Deschner about her process and ideas.

Robert E. Jackson in conversation with Jane Waggoner Deschner

Editors note: One of Deschner’s images is also included in Humble’s latest book: On Death, co-published with Kris Graves Projects, which you can get HERE.

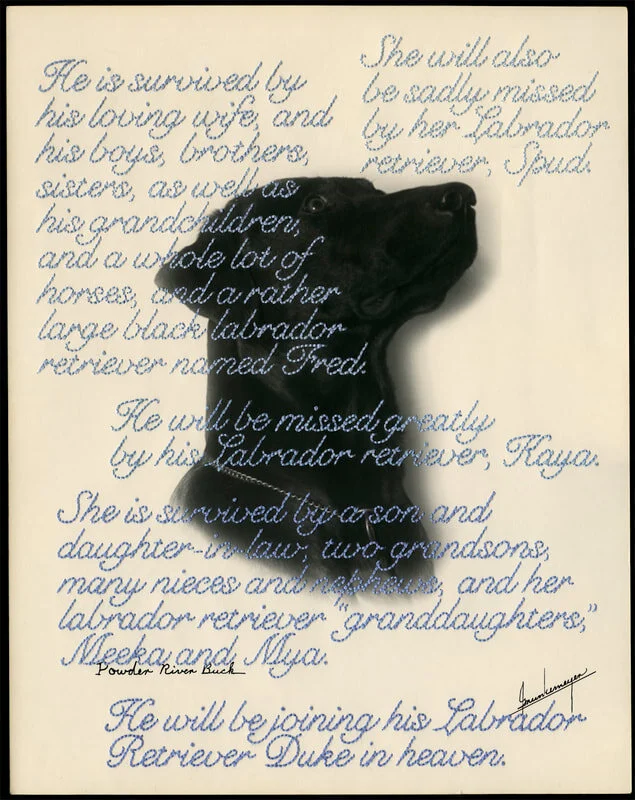

© Jane Waggoner Deschner. From the series Remember Me.

Robert E. Jackson: You have had a long and varied career in the arts. Tell us about what you did artistically before you became involved with photographs and embroidering on them.

Deschner: I’ve always made things with my hands; I sewed and knitted. In my thirties, I decided to try making art and enrolled at the local college to pursue art, earning a second bachelor’s degree. My preferred medium became photomontage using photographs from slick fashion and art magazines. In my early fifties, I wanted “to make better art” so I began an MFA program. I emerged from that experience still using found photographs, but now my focus was on snapshots and other kinds of everyday photos.

My last semester of grad school began in August 2001. And then the tragedy of 9/11 hit. My thesis exhibition was “The Anchor Project” in which I asked colleagues, friends, family members, fellow students, and teachers to send me a snapshot of someone/something/someplace that “anchored” them during this bewildering time. I received over 200 photos which I scanned and then returned to the sender. I determined from the content of the images and the explanations provided by the contributors that there were eight groupings.

People felt anchored by children (continuation); special places (orientation); a combination of special person/special place (interface); by being a member of a group (linkage); in how they relate to one other special person (accompaniment); in how another depends on them (interconnection); by pets (constancy); and through action(s) (occupation). I photoshopped the photos from each onto snapshots of my refrigerator and printed out the final pieces as large posters. The project was an absolute joy to create and I fell in love with the personal photograph.

The brochure from The Anchor Project - Jane Waggoner Deschner’s 2002 MFA thesis exhibition responding to September 11. Friends, family, and colleagues were invited to bring a snapshot of something that “anchored” them.

Jackson: What individuals in the art world have been an influence on how you see the world and your approach to creating something tangible from that?

Deschner: I always return to the guidance I received in grad school from the interdisciplinary artist, Ernesto Pujol. He counseled, “When you know why you choose the images you choose, you can choose more and better.” The first artists I was asked to study were Hannah Höch and John Heartfield. From there, I discovered John Baldessari. Christian Boltanski and Annette Messager. I enjoy looking at art that has a strong basis in craft: Liza Lou, El Anatsui, Gee’s Bend quiltmakers. And, of course, the Pictures Generation artists for using appropriation and montage, working in an area between high art and everyday imagery. These days I rely on thoughts/insights/support from artist colleagues as well as friends I’ve made in the community of collectors and dealers of everyday photos.

Alley, automobile, 2008. © Jane Wagoner Deschner. From the Underneath series.

Jackson: What made you make the connection between photography and needlework such that you wanted to make art from the combination of the two mediums? Does this hybrid art form limit or free you?

Deschner: After I fell in love with the found snapshot, I began buying large lots on eBay. I wanted all the mundane ones that collectors rejected. Scanning in high resolution and then processing in Photoshop allowed me to identify and focus on the wealth of information captured within each. For instance, in my “Underneath” series, I scanned a snapshot, cleaned up distracting scratches and dust, then obscured one element with a distinctly-colored geometric shape. This processing involved tiresome hours at the keyboard.

My hands needed to always be busy, so evenings while I watched television, I’d knit child-size sweaters. In 2008 I remembered how children’s lacing cards utilized stitching, and the thought occurred to embroider a photo (a scary move…poking holes in this one-and-only artifact). My hand was back in my art. By stitching quotes made by famous people, I could moralize in addition to emphasizing how fascinating an everyday photo was.

I’m not a photographer or a skilled needleworker—which in some ways is both freeing and limiting. But I’ve found a way of artmaking that works well for me. On an application form when I am asked to check what medium I work in, the only one that isn’t misleading is “Mixed Media,” but it’s also not particularly descriptive.

© Jane Waggoner Deschner. From the series Remember Me.

Jackson: For several years you’ve been focused on one project, Remember Me. What’s the story behind this work?

Deschner: I grew up with Unitarians and their principle of “the inherent worth and dignity of every person.” In 2015 the world/our country was becoming increasingly polarized. As with “The Anchor Project,” I wanted a way to process the situation and find hope. “Remember me: a collective narrative in found words and photographs” depicts our collective narrative, reminding us that we are more alike than we are different.

I hand-embroider anecdotes from family/friend-written obituaries into found studio portraits or snapshots. I create empathetic connections, demonstrate our common humanity. I’ve made over 750 pieces so far. Daily it brings me joy; unfortunately, the need to be reminded of its thesis shows no signs of abating. I see myself continuing this project well into the future.

© Jane Waggoner Deschner. From the series Remember Me.

Jackson: In reading more obituaries than probably 99% of the people in the world, what did you discover about them which you hadn’t thought about or realized and how did that affect your approach to using them in your work?

Deschner: While there are professional obituary writers, most obits we read in our local papers and online are written by the family or friends of the deceased, sometimes with the assistance of the funeral home. The goal is to memorialize the person in a thoughtful, loving way. In all the ones I’ve read, I’ve only seen two that contained bitter comments. After a life’s details are given, insightful, often delightful, anecdotes are shared.

“He had a great mechanical aptitude and could fix (or break) nearly anything.” “She had a very busy nature about herself and could hardly stand to sit still.” Sometimes the writer reflects: “We wish we could know the man he would have become.” I want viewers who engage with my work to experience a range of reactions as they move from piece to piece—amusement, recognition, sadness, sympathy—while realizing that all of these sentences were taken verbatim from published obituaries.

© Jane Waggoner Deschner. From the series Remember Me.

© Jane Waggoner Deschner. From the series Remember Me.

Jackson: Death can be a depressing and painful subject for an artist to confront.

Deschner: I chose other people’s photographs as my art medium in 2001 and I know why. My mother died when I was thirteen after being diagnosed with breast cancer three and a half years earlier. In the early 1960s, no one spoke about cancer, dying or death. I’ve tried, through my life, to “make friends with death.” To engage, ponder, acknowledge, accept. Susan Sontag wrote, “All photographs are memento mori.” Roland Barthes stated, “Every photograph is a certificate of presence.” Obituaries by definition describe an individual’s life because of the circumstance of it having recently ended. This project is about lived lives…within our shared specter of death.

© Jane Waggoner Deschner. From the series Remember Me.

Jackson: You have recently been fascinated with doilies as a subject in your work. Tell us a little about how that happened and how you wish to incorporate that object within your art.

Deschner: I started going to thrift stores to find affordable frames in which to present this project. I paint them with black gesso and mount the stitched photos on black mat board. While looking around, I noticed the discarded doilies and afghans that were for sale for less than the cost of the yarn or thread and were most probably made by women. Because of my years of knitting, I knew the time, skill, expense and love that went into making them so I started buying them.

I decided to stop buying afghans when such purchases totaled $100—that was over 50 pieces! But doilies I can’t resist. There is a tactility in their intricately crocheted rounds and rectangles. I “feel” the hands that made them and want to honor that energy and skill. I’m rescuing something made with love that was discarded by loved ones and examining it/them in a contemporary context—paralleling my work with found photographs.

So far, I’ve presented doilies in two non-traditional ways: as curated stacks or mounds (of up to 100 or more) and in frames behind hand-colored photographs with quotes about handwork. For example, one of my pieces uses this obituary quote: “Each of her children has a snowflake she crocheted.” I bought thread and crochet hooks and am trying to teach myself to crochet a doily via YouTube. It’s really not easy and has led me to an even greater appreciation of the skill needed for this type of needlework.

© Jane Waggoner Deschner. From the series Remember Me.

Jackson: As an artist who has been working for many years, what advice would you give younger artists about their journey in the pursuit of making art and having their work acknowledged and shown?

Deschner: Here is what I tell young artists (when asked): I believe that everyone should make the best art they can—art that truly expresses what they want to learn about themselves and share with the world. That work will be authentic and better than making something you think people will like—and eventually will generate acknowledgment and exhibitions. Start building a network with the people around you and work to a wider audience both in numbers and geography.

No one will come and find the glorious work you make; you have to put yourself out there over and over, time after time, place after place. Maintain old contacts and keep making new ones. Support fellow artists. Always show up and work. Make some sort of art every day. Get a day job if you have to, so you can make your work.

© Jane Waggoner Deschner. From the series Remember Me.

Jackson: A generation ago, you were asked to think about “why you choose the images you choose.” Today, how would you answer?

Deschner: I want my work to affect change in viewers’ hearts and minds. To answer my “why” question, substitute “create” for “write” and “art” for “literature” in this quote from James Baldwin. ”You write in order to change the world, knowing perfectly well that you probably can't, but also knowing that literature is indispensable to the world. The world changes according to the way people see it, and if you alter, even but a millimeter, the way people look at reality, then you can change it."

© Jane Waggoner Deschner. From the series Remember Me (Labrador Retriever)

Jackson: Where do you go from here? Where do you see your artwork and vision taking you next?

Deschner: I entered my seventies a couple of years ago. I feel the horizon coming closer and closer. I hope to make art for many more years (artists are fortunate because we never have to retire), but the reality of having limited time left is increasingly “real” as my body and brain age. In two years, I will have lived beyond the life spans of both my parents and a younger sister. I feel an urgency about making art now that I didn’t have even five or ten years ago.

I’d never thought of myself as a feminist until receiving this comment from Ernesto Pujol during grad school: “She is a person in a small city, who is a woman, a mother, a former wife, a partner, who is making art about life…processing the domestic—what feminism was and is at its core. It’s the hardest art to make—to take daily life that is so dismissed, unappreciated, under-appreciated in popular culture, and put it into a new spin.” It is our interaction with the ups and downs experienced in daily life that I will continue to explore with photographs, quotations, and thread.