Marcel Duchamp with Shaving Lather by Man Ray

An exhibition of rare photographs at the Philadelphia Museum of Art shows how photographers helped shape artists' public personas.

Face to Face: Portraits of Artists, up through October 14th, is a curious exhibition in terms of what it reveals about the way its curator and the other exhibition planners think about their audience. What do they assume the viewers already know before they walk in the door? What do they expect the audience will want to learn from the show?

I always prefer curators to give an audience as much information as they think they can handle. In my mind, if you’re coming to a show of largely black-and-white photographs (versus an attention-grabbing headliner like Van Gogh or Monet), you’re probably already a little interested in art, and thus interested in learning about the artists responsible for the photographs. Unfortunately, the gaps and lacunae in the display of Face to Face come together to present a rather muddled, unsure portrait of who the anticipated audience for this show is, and leads to some frustration and, ultimately, a sense of unfinished business for this avid museum visitor.

Exhibition Review by Deborah Krieger

Paul Robeson and Eslanda Goode Robeson - June 1, 1933 by Carl Van Vechten.

Gelatin silver print Courtesy of Philadelphia Museum of Art, Gift of the artist, 1949, 1949-20-2

The label text in Face to Face, for example, is much more heavily weighted in favor of the famous subjects of the images – such as Frida Kahlo and Marcel Duchamp – and doesn’t tell us much about who the photographers are, or what their connections were to their subjects (with the exception of Julien Levy’s Kahlo portraits, because their intimacy can be explained by the fact that they were lovers or the portraits Alfred Stieglitz took of Georgia O’Keeffe, who was his wife). How did Edward Steichen come to create such a magnificent Rembrandt-esque image of Alphonse Mucha, its shadowy depths and soft, blurred edges so different from the Czech painter’s decorative flair? Face to Face assumes viewers don’t want to know.

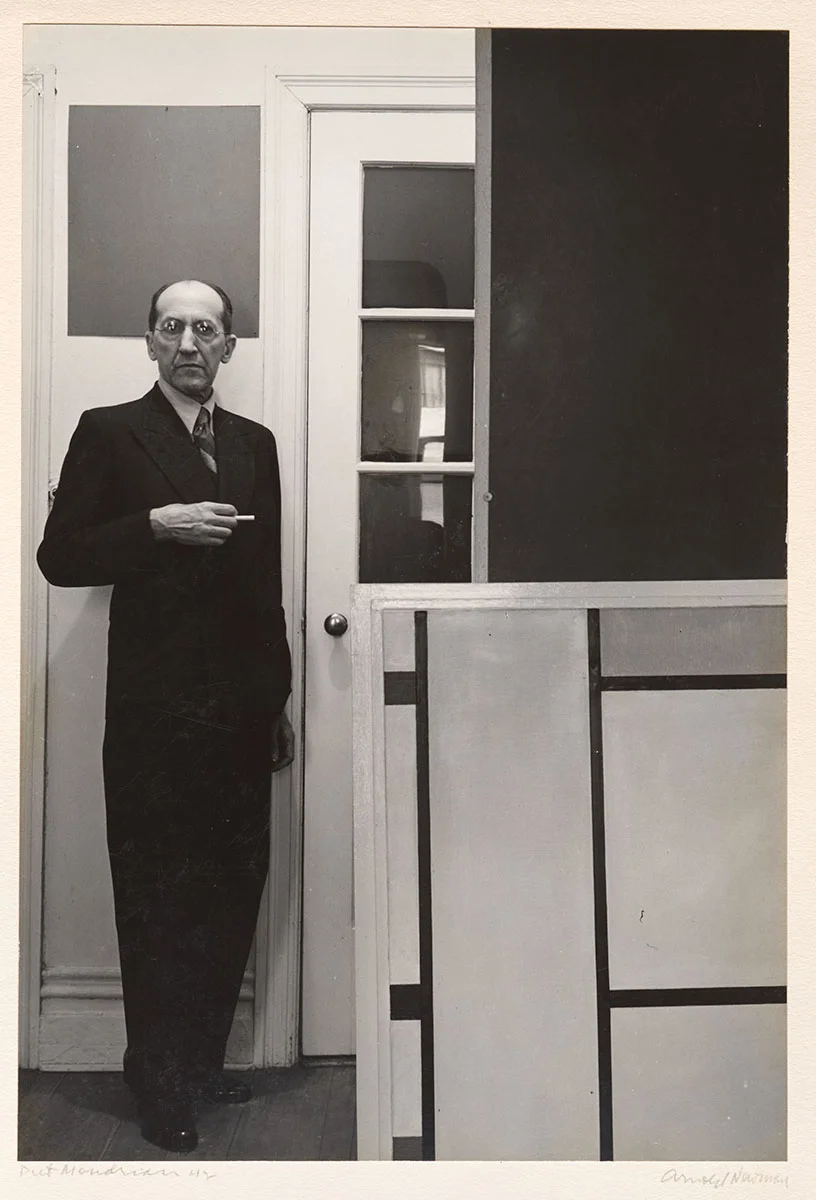

Piet Mondrian by Arnold Newman, 1942. Gelatin silver print

Courtesy of Philadelphia Museum of Art, Gift of R. Sturgis and Marion B. F. Ingersoll.

There are still many positive elements to be found in Face to Face, although they’re more due to the brilliance of the works on display – all part of the Philadelphia Museum of Art’s permanent collection – rather than how they’ve been exhibited. The first significant cluster of photographs in Face to Face presents various stars of the 1940s art scene – Leger, Mondrian, Yasuo Kuniyoshi, Hopper, Calder, et cetera –in a salon-style hanging. Presented in this dense crush of images, Newman’s genius in the treatment of his subject matter is clear: in many cases, he’s taken a cue from the artist’s own style in constructing his image of them, the final photograph works as a synecdoche in approaching the oeuvre of the subject. The portrait of Mondrian shows the man himself standing in front of a series of windows and doorways whose strict geometric linearity is an obvious nod to de Stijl.

Likewise, Hopper is viewed through an open doorway, pushed far into the background of his own composition, mimicking the emotional distance and remove of Hopper’s own figures and compositions. The double portrait of Moses and Raphael Soyer depicts them almost as broken mirror images of one another, symbolizing their closeness and affinity, but also their adjacent places in the art world and similar Social Realist painting styles.

Edward Hopper by Arnold Newman, 1941. Gelatin silver print

Courtesy of Philadelphia Museum of Art. Gift of R. Sturgis and Marion B. F. Ingersoll,

Eudora Welty by Jill Krementz

There are individually-installed works that shine wonderfully as discrete objects. Jill Krementz’s portrait of Eudora Welty, placed in a corner of the gallery space, is beautiful and haunting. The writer is presented in profile at her desk, almost in silhouette, in front of blindingly bright open windows. While the lack of detail given to Eudora herself might make this image seem remote, a peek at the lower foreground of the photo reveals what appears to be a bed frame and rumpled, pale sheets, as if Krementz is sitting on Welty’s bed with her camera.

Of course, the lack of information given in Face to Face about Krementz, and how she would have the opportunity to photograph Welty, means that interpreting the positioning of Krementz as the viewer sitting in Welty’s bed is pure speculation. Edward Steichen’s photograph of Alphonse Mucha, as I mentioned before, is brilliantly rendered and sensitive, while Thomas Carabasi abstracts and refracts Lamont Steptoe in a truly thrilling way.

Lamont Steptoe, Poet, 1987. by Thomas Carabasi

Gelatin silver print, toned

Courtesy of Philadelphia Museum of Art, Purchased with the Alice Newton Osborn Fund, 1989

Muriel Streeter in Frida Kahlo’s Clothes by Julien Levy, 1938

Gelatin silver print. Courtesy of Philadelphia Museum of Art, Gift of Sally Jane Kuhn, 2015, 2015-38-1

Julien Levy’s portraits of Frida Kahlo are stunningly relaxed, providing another view of the artist who is so associated with pain and anguish; more curious still is the single recently-uncovered portrait Levy created of his future wife Muriel Streeter wearing the clothes Kahlo has cast off over the course of the session. It’s as if this image of Streeter predicts how Kahlo’s look would be later commodified as the artist herself became an icon--more the braids, eyebrow, and dresses than a real, breathing person.

Another large cluster at the back of the gallery space depicts Carl van Vechten’s portraits of various Harlem Renaissance figures such as Zora Neale Hurston and James Baldwin, along with entertainers Marian Anderson, Bill Robinson, and Ella Fitzgerald and writer Truman Capote. The images range from formal and reserved, as in the portraits of Hurston and poet LeRoi Jones, to playful, as in Fitzgerald, to meditative, as in Langston Hughes and Beauford Delaney.

This display, however, is one of the biggest barriers to entry (and pure enjoyment) of Face to Face: namely, the decision to give biographical details of some but not all of van Vechten’s subjects led me to wonder in bafflement who the audience was for this show? What audience member knows about fashion photographer Cecil Beaton, pictured near the center of this cluster, but not Zora Neale Hurston or painter Aaron Douglas, both of whom receive short biographical blurbs? Indeed, I only learned who Beaton was earlier in 2018 when I watched the recent documentary about his life, and he’s certainly as well-known (or not) as Hurston or Douglas.

Muhammad Ali by Sonia Katchian

The most provocative statement in the show comes in the form of a single photograph: beneath a Paul Strand portrait of poet Ernie O’Malley is Sonia Katchian’s intense, low-angle view of Muhammad Ali, the famous athlete, and activist. The wall text argues that Ali lived a “creative” life; while the sentiment is certainly much bolder than I’d have expected from such a traditional show, I think it could have used a little more elaboration. Was Ali, in this sense, a sort of performance artist? Are all “great athletes” who “inspire” others the same as “great artists”? I’d almost have liked to read an essay about this topic, although my curiosity was certainly piqued by the inclusion of the Katchian work alone.

Lastly, the cluster of works closest to the end of the exhibition space linked past and present in a way I found satisfying and effective: adjacent to a lineup of photos of Marcel Duchamp in various poses, settings, and guises by artists like Man Ray is a portrait of drag queen Mario Montez by Conrad Ventur, connecting the more contemporary image of Montez to Duchamp to the latter’s female “Rrose Celavy” persona. While I would have preferred to place the Ventur image closer to the terminus of the gallery to better mimic the flow of chronology, it was a charming reference that was like a bonus for viewers to make on their own, without an explicit parallel drawn in the label text.