© Andrew Waits

Andrew Waits photographs Seattle's evolving landscape as dark, uncomfortable footnotes.

Aporia – a term attributed to the early dialogues of Socrates – is often tied to feelings of doubt, confusion or impasse, and has been associated with meandering, unsuccessful attempts to process trauma. It's also the title of Seattle-born photographer Andrew Waits' recent series and limited edition photobook, which he uses to address the emotional gravity of his native city's rapid economic and architectural boom.

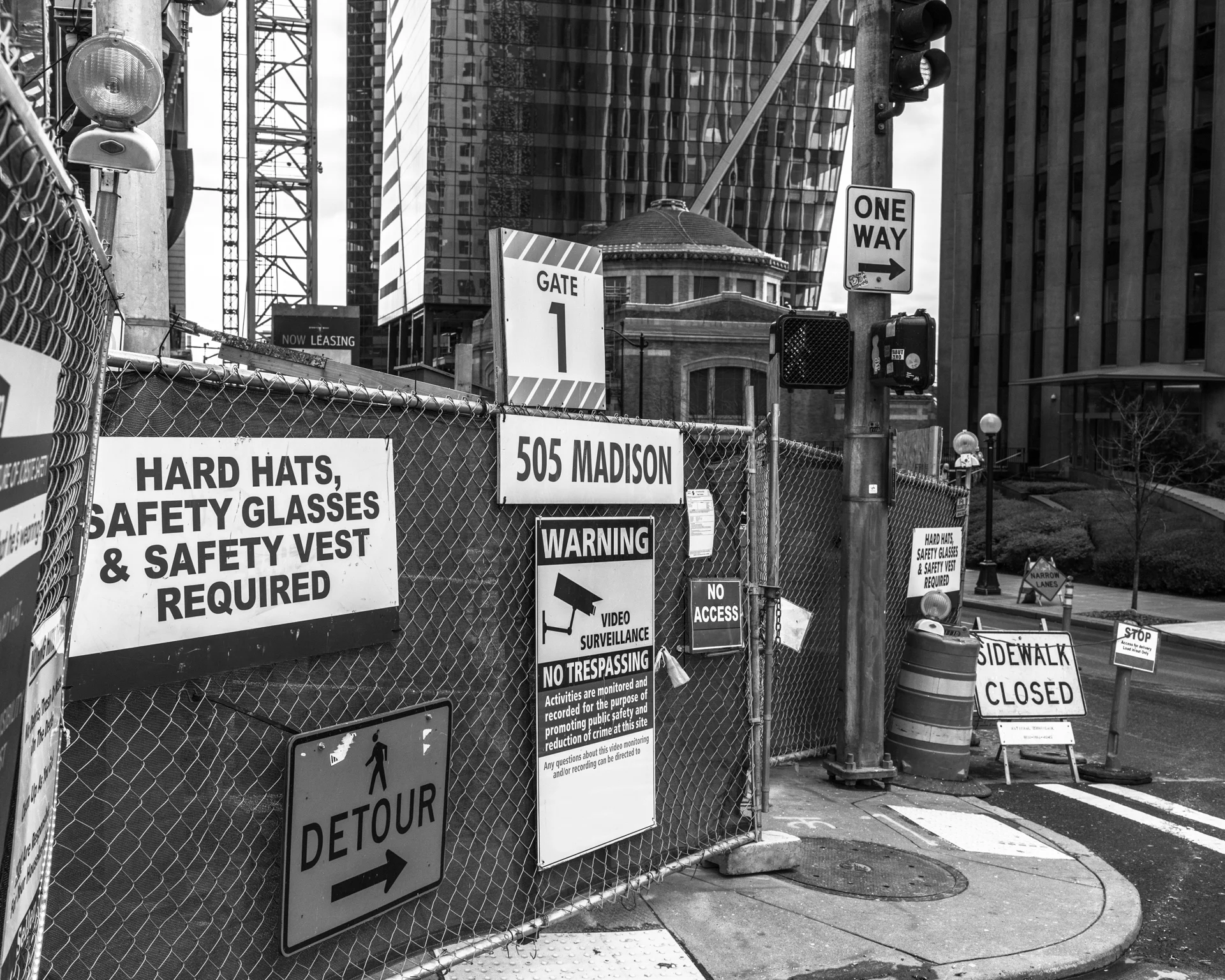

Waits' black and white photographs look at the city's shifting skeleton and its impact on the human psyche. In contrast to his earlier, more traditionally documentary style and day job as a freelance editorial photographer, Waits approaches urban development and gentrification with a brooding, poetic gaze. Buildings battle with light and shadow, foliage juts in where it can, and people, when sparsely represented, bend like branches under increasing weight.

I corresponded with Waits to learn more about the metaphors and new directions in his work.

Interview by Jon Feinstein

© Andrew Waits

Jon Feinstein: How did you start working on this project?

Andrew Waits: I started making this work on the heels of another project based about 8 hours away in Southern Oregon. My initial goal was simply to make something local. I grew up just north of Seattle and have lived in the city my entire adult life. Perhaps due to the relative youth of the city, I always felt a level of intimacy and ownership with it. For as long I can remember, I’ve identified with its temperament and landscape.

However, the past several years, the pace of change in the city has accelerated. People have been priced out, the population has exploded, and landmarks have been torn down and replaced with expensive restaurants and condominiums.

© Andrew Waits

© Andrew Waits

Feinstein: In your statement, you mention an interest in the "man-altered" landscape. My first thought was 'oh, the New Topographics,' but your images don't, at least on the surface, resemble those at all. They're cruder, darker, apocalyptic.

Waits: While there is some overlap in our concerns regarding the man-altered landscape, our treatment of the topic is quite different as you mentioned. The photographers in the New Topographics show used ambiguity and a lack of style as a statement and methodology to evoke. They were interested in fostering an ambiguity around the pictures' attachment to the world, and the maker's attachment to a particular subject.

My photographs, on the other hand, are not entirely stripped to the point of sterilization. Lewis Baltz once said that he used photography to distance himself from the world he loathed and was powerless to improve. While I share his sense of powerlessness and loathing to a certain degree, I would not go so far as to say this work is driven by the latter.

There is an undeniable fascination with chaos and a fundamental pleasure in seeing in many of the photographs. I intentionally include details within the environment which allow the viewer the capability to read into the meaning of the photograph and the intention of the photographer.

© Andrew Waits

Feinstein: There's an image of two beams shooting up into the sky. I can't help but see a nod to September 11th, especially with the other images of pillars, columns, etc. Am I off base?

Waits: Not entirely. I can see the similarities, however, it wasn’t meant to be a direct reference. What I’m more concerned with is what these things symbolize in relation to past history, erased history, and anticipated history. The Chinese photographer Sze Tsung Leong deals with this juncture specifically in his series, History Images, in which he photographs new and old China. He suggests that the smashing of the old world led to the erasure of history and left a new world populated by emptiness.

While I’m not specifically nostalgic for the past, I am troubled by the artificiality and temporality of what we build. The pillars and columns to me symbolize not just the past, but longevity and an appreciation for culture. Also, in reference to your question about the two beams of light, I actually see them as shooting down rather than up, as if something divine is touching the construction site, blessing it.

© Andrew Waits

Feinstein: Did you feel this way when you first took the photo or did that feeling emerge later in the project’s conception?

Waits: I think I started to see them this way after reading Daniel M. Abramson’s book, Obsolescence, in which he investigates the logic behind architectural expendability. He argues that the act of replacing the old with the new, regardless of its actual obsolescence, helps people assign meaning to the unsettling, fast-paced change of capitalism. So these two divine beams of light represent a false justification for the constant destruction and construction.

© Andrew Waits

© Andrew Waits

Feinstein: Tell me more about your interest in The Situationists and their backdrop to this work.

Waits: I came across the work of The Situationists and specifically the French artist and philosopher, Guy Debord at some point during the process. I was not at all interested in directly documenting gentrification and urbanization in a specific city for a variety of reasons. The primary question I was compelled to address was the effect of rampant urban dynamism on the psychology of the individual and the populace. This question relates closely Debord’s 1955 term psychogeography.

Essentially, psychogeography is the study of the laws and effects of the geographical environment on the emotions and behavior of individuals. Debord found some architecture to be physically and ideologically restrictive, creating an undertow that forced a certain system of interaction with the environment. To break from this undertow and properly observe and study it, he developed the act of "dérive, or drifting.

These unplanned dérives required that participants drop their everyday relationship to an environment and let themselves be drawn by the attractions of the terrain. In an effort to avoid making something didactic, I really tried to divorce myself from time and from any sort of predetermined purpose or concept. Essentially, I allowed myself to become lost in my own city in an attempt to react on a deeper level of instinct and begin to chart a psychological landscape.

© Andrew Waits

© Andrew Waits

Feinstein: People play a curious role in this work. They're sparse, architectural figures – shrouded by shadows, covering their faces or looking off with eyes closed.

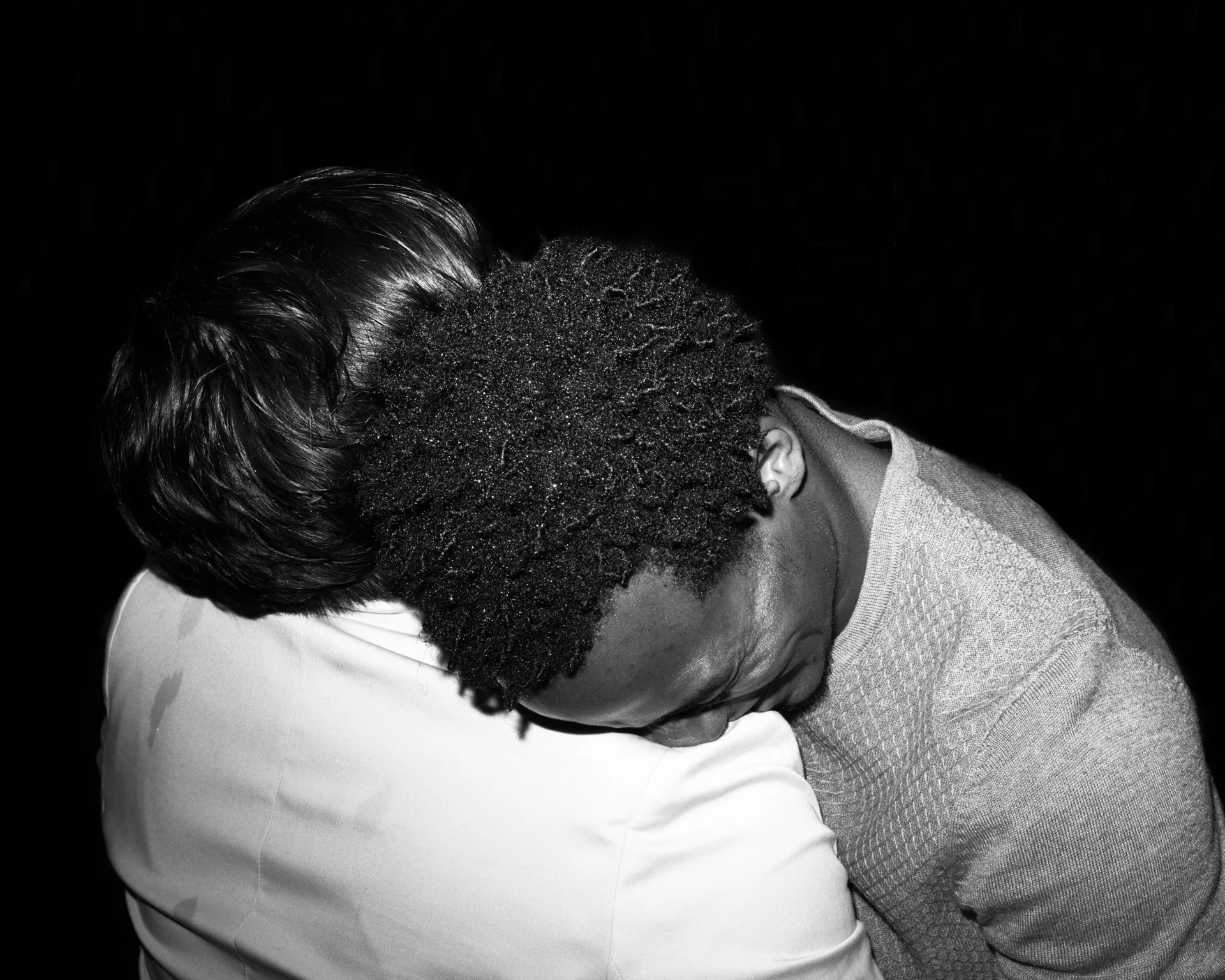

Waits: There are not many people in this work, but the ones that are included are essential to me. I can put them in two general categories, which also makes much more sense in the context of the book. There are the people seen within the urban environment and those surrounded by darkness.

The figures within the urban environment are restricted in one way or another. Their identities are consumed and dominated by the environment leaving them either faceless or robotic. To me, they reflect the abstraction of the urban environment and essentially the loss of the city’s soul.

The figures photographed in darkness are quite different. They are expressive and emotive in their gestures. These photographs are mixed throughout the series and serve as a sort of release. They are also strongly connected to the idea behind the title of the work, Aporia.

© Andrew Waits

© Andrew Waits

© Andrew Waits

Feinstein: Stylistically, this breaks from your earlier work which was more straightforward, documentary and typological in nature. What do you think prompted, triggered, etc your shift in "seeing"?

Waits: The work I was doing before was much more straightforward. I felt it was enough to simply show the viewer what something was, superficially – primarily because at the time I was far more concerned with telling the stories of my subjects than the photographs themselves. Therefore text and audio played a significant part. While I am proud of some of this work, there was always a creative desire which was not being fed.

© Andrew Waits

Feinstein: Where do you, personally, fit into all of this?

Waits: Intellectually, I understood this was taking place and very much opposed the way the city and corporate interests were handling it. However, I don’t think I realized the emotional toll it was taking until I started to photograph. I would walk for hours and hours without any specific plan or goal. Over time, I began to realize that what I was feeling as I took these journeys was coming through in the photographs. This idea of mapping how the physical geography of a city manifests itself internally was a huge jumping off point for me.

© Andrew Waits