Photo © Antone Dolezal

Photographer Antone Dolezal combines his own photographs with found materials to uncover Southwest mythologies. Stay tuned to the end of this interview for some cosmic NASA field recordings.

Nevada and California's deserts are thick with folklore and a history of photographic exploration. While playing host for the "manifestly destined" work of late nineteenth and early twentieth-century photographers like Ansel Adams, Laura Gilpin, and Timothy O' Sullivan, the regions were also home to passing transients and utopian communities. Likely because of their magical topography, these areas are often mythologized as a "gateway to the cosmos."

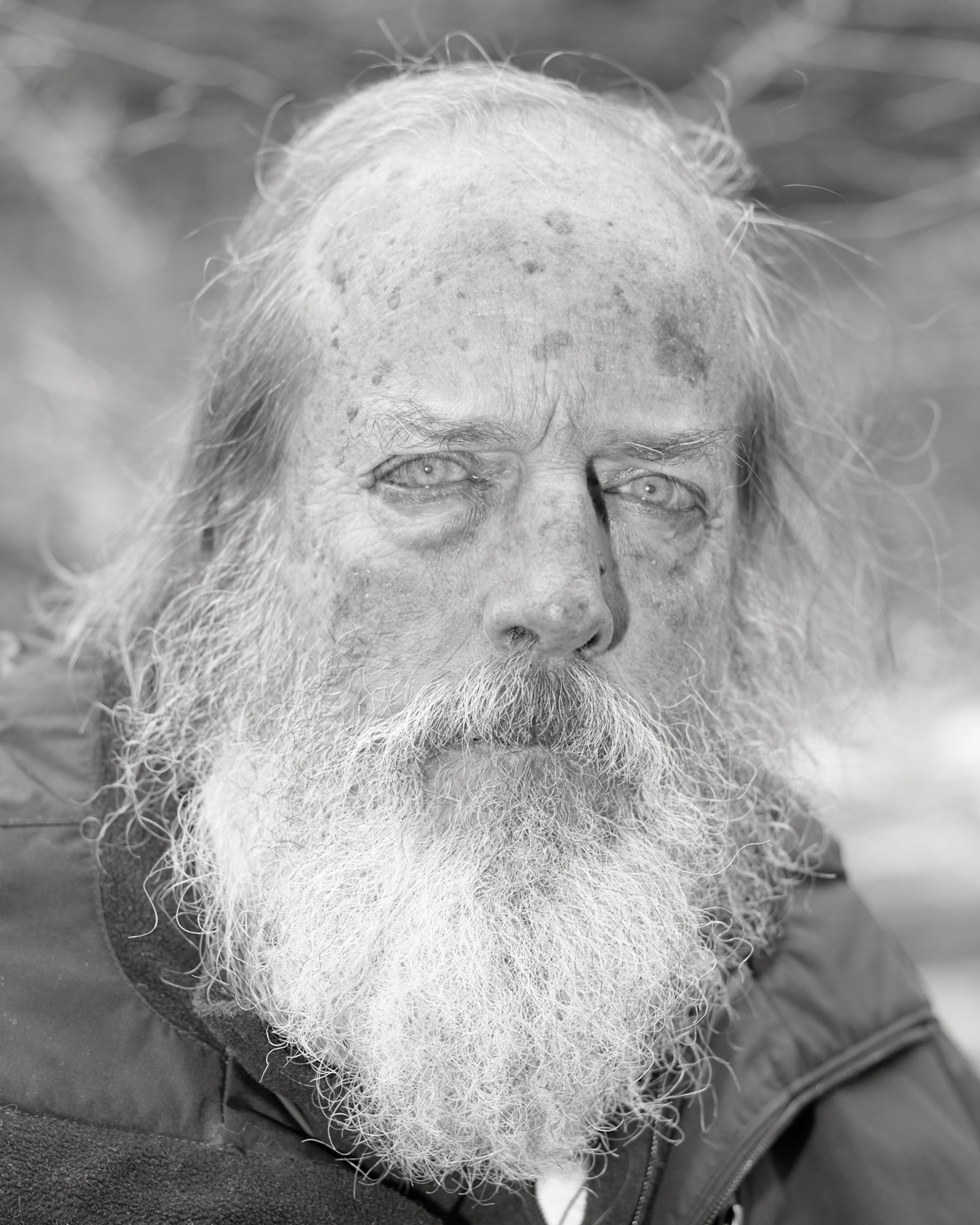

For the past few years, this has inspired Antone Dolezal's Part of Fortune and Part of Spirit, a series of photographs, texts and found images that play stories from these regions off classic science fiction tropes and contemporary religious tales. Unsettling black and white portraits volley against lush color landscapes and sci-fi movie-stills, and viewing them creates hybrid pangs of disorientation and nostalgia. Itching with confusion, I emailed Dolezal for some clarity.

Interview by Jon Feinstein

Photo © Antone Dolezal

Jon Feinstein: What prompted your investigation into the mysteries of the cosmos?

Antone Dolezal: A common thread in my work is how mythologies are formed and evolve and what the stories we create say about contemporary society. The most exciting mysteries are the ones that will never be solved and with this project, I was drawing links between both scientific and divine understandings of the cosmos… two modes of perception that draw influence from one another and are inherently linked.

My research into modern esoteric religious movements is fairly extensive and included a lot of reading and study alongside personal interactions and at times being invited to observe ceremonial practices with several of these groups. As I was deconstructing the mythologies I encountered, I found specific myths and storylines to be influenced by the folklore of the American West, science fiction writing, and cinema, as well as government conspiracy theories that linked together many of the movements I was researching.

It has been a multi-layered investigation into the many components of social and environmental situations that compose modern mythologies, my goal is to interpret my findings in a manner that provides the viewer with a different means of understanding how myths emerge and grow.

Photo © Antone Dolezal

Feinstein: This work focuses on landscapes in California and Nevada for their spiritual mythologies. Were there any specific stories that drew you to them/ to make this work?

Dolezal: I lived in Santa Fe, New Mexico for 10 years prior to moving to Syracuse, New York and the time I spent in the Southwest dramatically changed my perception of how one’s connection to the land can alter one’s own personal beliefs and sense of self.

That said, photography that romanticizes the American West makes me uncomfortable. In fact, it makes me so uncomfortable that I felt compelled to tackle my own issues with it through this work. Ultimately, I settled on operating within the dialogue of magical realism and explored the deserts of California and Nevada as a means to create an imagined landscape that could tap into the psychology of the people and stories I was researching.

Photo © Antone Dolezal

Feinstein: Was there a specific rhyme or reason to when and where you photographed?

Dolezal: Early on in the project, I found a map in Sedona, Arizona detailing all of the energetic vortexes in the Southwest and this helped guide me from one place to the next. Another tactic I used was to photograph just outside of Las Vegas and Los Angeles… places that symbolize the extremes of modern civilization, yet once I would leave these cities, I found myself on the periphery of the unfamiliar and unknown.

Photo © Antone Dolezal

Photo © Antone Dolezal

Feinstein: Your portraits add another layer of mystery. I know they are pictures of spiritual practitioners but have few clues about their deeper identities or psychology. In my mind, each person is a mystical stand-in for a larger idea. What was your mindset in making these portraits?

Dolezal: I think you’re right on point to interpret the portraits as a mystical stand-in for some deeper message. When piecing together this narrative, I’m thinking about the potential abilities of the photograph to sustain and challenge its foundation of punctuating metaphor. What follows are the ingredients omnipresent in magic realism: where the distant past is present in every moment and the future has already happened.

I’ve created an imagined world reflecting a reality that is presented outside of time. This accounts for the same character being played by different actors of different ages, archival photographs that have been composited with my own contemporary images, etc. Here, time is not linear and the magical and ordinary are one and the same.

Feinstein: Does your relationship with these people matter?

Dolezal: I operate in the traditional way of going out into the world, wandering around the desert for a month or so and making portraits through the process of meeting people. If I begin to build a strong photographic relationship with someone, I try my hardest to convince them to sit for me multiple times and for hours on end until the photograph is realized. There is an investment from both parties, and these relationships are incredibly important.

Photo © Antone Dolezal

Photo © Antone Dolezal

Feinstein: Where does spiritualism fit into your own life?

Dolezal: All of my projects center on the ways humans find meaning in life. I consider my work to be a reflection of how I orient myself in the world and as I evolve as an individual and find challenge in life, it will be present in the work I am producing. I do think there is a certain level of mindfulness required to register the gifts the universe gives out, so take that for what it’s worth, but ultimately I prefer not having fully formed opinions when it comes to my own personal spiritual beliefs.

Photo © Antone Dolezal

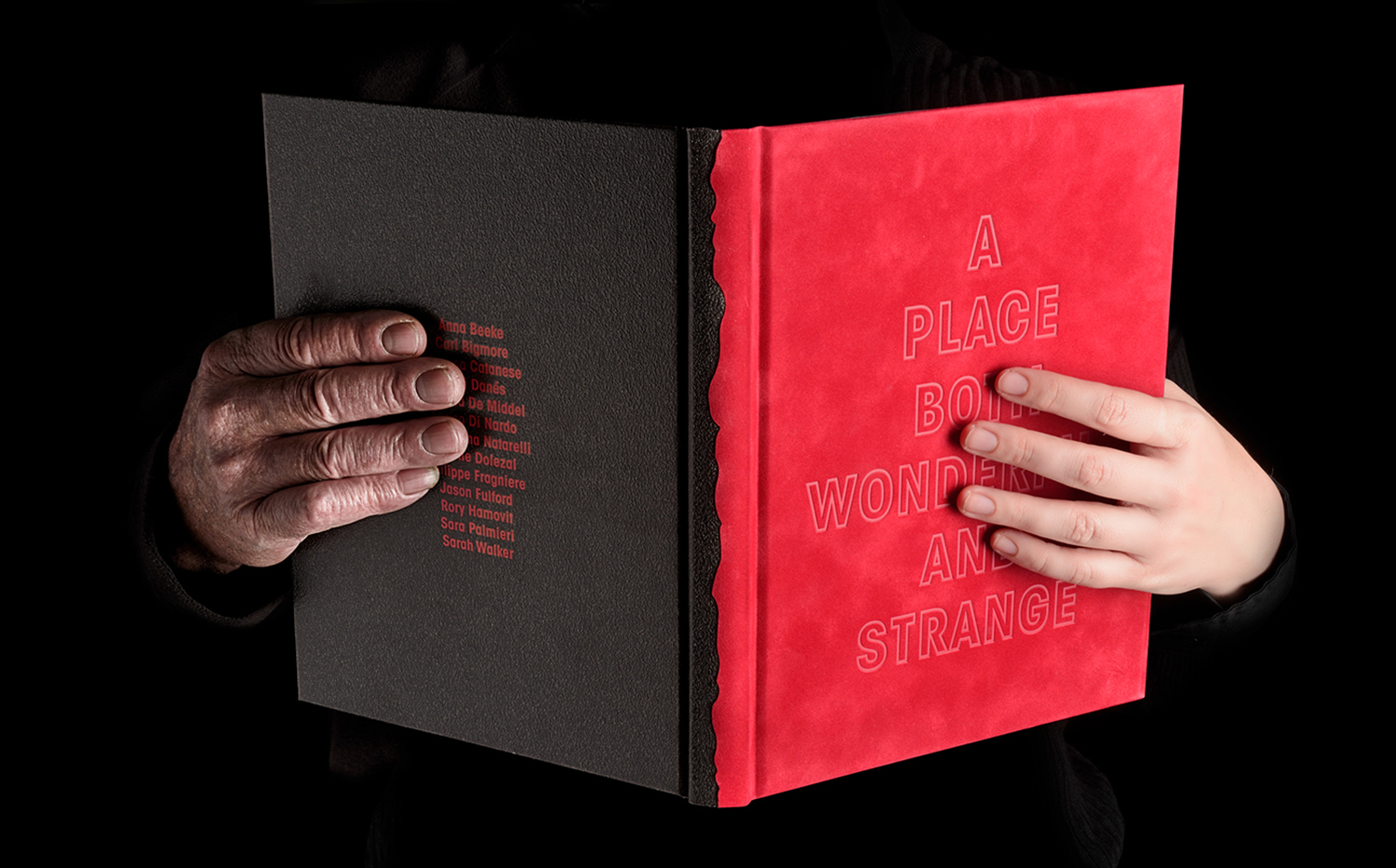

Feinstein: Congrats on your inclusion in the Twin Peaks book: A Place Both Wonderful and Strange. It was one of my favorite photobooks of 2017. How did your participation come about?

Dolezal: Gustavo Alemán from Fuego Books had seen my collaboration with Lara Shipley, Devil’s Promenade, and reached out to see if I would send a proposal of new work for consideration. At this point, I had been working on Part of Fortune and Part of Spirit for a few years and decided to propose a side narrative to the bigger body of work. I titled it A Void and Cloudless Sky – a reference to the Buddhist passage Agent Cooper recites aloud to comfort Leland Palmer as he lay dying on the floor of his jail cell – hoping the title would evoke the cycle of life, death, and rebirth present in the accompanying story I wrote.

I approached the sequence in a manner that never directly references Twin Peaks, yet draws influence from the psychology and overwrought symbolism apparent in much of David Lynch’s work.

A Place Both Wonderful and Strange © 2017 Fuego Books

Dolezal's photographs in A Place Both Wonderful and Strange © 2017 Fuego Books

Feinstein: There's been a resurgence in photographers playing their own pictures off of found materials. When it works (in your case), it's hard-hitting and poignant, but I've also seen it fall flat. I think Joerg Colberg coined the term "The [Christian] Patterson Effect." What draws you to working in this way?

Dolezol: Within the context of my work, I often excavate a historical record of evidence that gives me a grounding to begin to make my own photographs. So I generally start with the archive as a means to comprehend how my subject matter has been represented in the past and then I use that material to re-imagine and re-interpret that history within my own work.

There is a lecture I occasionally give centered on artists who use archival materials that trace the influence of historical events and globalism with important movements from the Dadaists to the present. I have found it to be successful in helping students understand that important movements – or trends – in art don’t appear out of thin air, but rise from a pre-existing and interconnected dialogue.

What I personally find most exciting about the lecture is when we deconstruct the work of contemporary artists because there is such a rich potential for archival materials to provide an alternative understanding of how we interpret history and contemporary social issues. A few of the artists we look at are Broomberg & Chanarin, Mariken Wessels, Fred Wilson, David Campany’s A Handful of Dust and of course Christian Patterson’s Redheaded Peckerwood… the lecture is actually followed by a screening of Terrence Malick’s film Badlands!

© Antone Dolezal

Feinstein: As an educator, do you have any advice for photographers who are intrigued by this, but terrified of the critics?

Dolezol: If I have a student who wants to explore how archival materials can function within their work, I’m always on board, but I reiterate the importance of serious research and consideration because they will be competing with some really smart and significant works. Another piece of advice I often give is that the archive can be a source of inspiration to gain insight on what is missing from a project… sometimes it’s just a matter of looking at found materials and then going out into the world to make your own photographs.

© Antone Dolezal

Feinstein: Has making this work given you clarity or confusion on the mysteries of the cosmos?

Dolezal: The research involved in this work has certainly given me a better understanding of why we look for meaning in what seems to be an increasingly meaningless and violent world. I’m fascinated by the stories and beliefs that can bring us together, yet also separate us from each other. One reason I work within the dialogue of magic realism is to abstractly convey the possible realities experienced by those who hold beliefs often viewed to be on the periphery of contemporary society.

I think it’s fairly obvious that we don’t all live in the same reality, and with this work, I tried to tap into the psychology of those who hold a numinous perspective about the world and view supernatural events to be just as ordinary as the sun rising in the morning. I’m completely fascinated that there are realities present where both the mystical and mundane intertwine to make a world that can still be seen as enchanted and mysterious.

Photo © Antone Dolezal

Feinstein: One final question, I promise! If you could make a playlist to complement this work, what would be the opening song, and what would be the closing song?

Dolezal: I’ll have to go with the sound recordings from space that NASA released. I’m working on some strange sound pieces that are very similar to go along with the installation of this work, but they aren’t perfect quite yet! (Editors note: the actual sounds start at 33 seconds in -- sit through the initial text, it's worth it!)