© Jay Turner Frey Seawell from National Trust

Jay Turner Frey Seawell's National Trust Investigates Media and Political Power in the United States

In 2011, Washington DC-based photojournalist-turned-art-photographer Jay Turner Frey Seawell began photographing political architecture in the United States as a metaphor for the structures and relationships of power they represent. As 2012 approached, he expanded his focus to capture the media surrounding the United States presidential election, a larger series he titled National Trust. Using various locations around the country as his backdrop, Seawell approached this landscape with images ranging from news reporters, to the somber historical architecture and its looming facades. Anchormen appear silhouetted on stage curtains, reporters seem disfigured behind LED lights that cast them as strange mechanical robots. Smart phones and dictaphones swarm candidates, grabbing for a sound byte.

Pulling apart the seams of contemporary news production, National Trust, published at the end of 2016 by Skylark Editions, humorously explores the spectacle of politics, power, and the stories that report on them. In some ways, Seawell's work calls to mind the playwright Bertholt Brecht, who famously made stage cues and other mechanics transparent to his audience, revealing their alienating intents. While initially shot an election-cycle ago, Seawell's work feels increasingly current, especially in light of today's tumultuous relationship between the media, public, and those in positions of power.

I corresponded with Seawell to learn more about his work and ideas.

Interview by Jon Feinstein

© Jay Turner Frey Seawell from National Trust

Jon Feinstein: What inspired National Trust?

Jay Turner Frey Seawall: National Trust came into being during my first visit to Washington, DC. I had never been to DC until early 2011. I went there to visit a friend and I photographed around the city without initially having a particular project in mind. What struck me as I walked around the downtown and National Mall areas was the prevalence of classical style architecture. This type of architecture can be found in numerous U.S. cities, but it’s such a dominant architectural form in the heart of the capital. The project was initially a series of photographs about Greco-Roman style architecture because I was interested in these heavy associations between this country and ancient Western empires. As the project grew, I began to photograph other subject matter, such as political rallies during the 2012 presidential campaign.

© Jay Turner Frey Seawelll from National Trust

© Jay Turner Frey Seawell from National Trust

Feinstein: The bulk of this work was made during the 2012 election. Has today's shifting political climate impact how you think about this work?

Seawall: Even though I photographed different subjects and settings throughout this project, ranging from institutional architecture to political campaign events, I always thought that the connective thread in this work is this attention to surface appearances and the heavy influence that they hold over us when we try to understand power and politics. Many conversations that I had with people centered around the power of surface appearances in our culture, and that was on my mind for awhile. Even so, I still had no clue how powerful appearances truly are until this most recent election. What I mean is that our country elected a celebrity and a reality TV star with no prior political experience. What we get is a bunch of showiness and braggadocio and insults instead of substance or understanding of critical issues. Our country has enabled Trump for awhile now, and his election is celebrity worship taken to the extreme, not to mention worship of wealth and materialism. The pictures in National Trust can be seen as the buildup to this awful culmination.

© Jay Turner Frey Seawell from The Mall

Feinstein: I know the series is complete, but have you thought about revisiting it given our current state of affairs? Any plans for a followup? Do you see your more recent series, The Mall operating in dialogue with this work?

Seawall: I don’t have any plans to revisit National Trust. Many of the pictures depict political gatherings and spectacles, and I think I’m done with that. I suppose that anything could ultimately be considered political, so if my work is going to continue to be political, then perhaps it will be political in less overt ways.

I do consider The Mall, my more recent work, to be in dialogue with National Trust. It is assumed at times that all the pictures from National Trust were made in DC, and understandably so. However, I made these pictures in various places around the country, and I wanted to work on another project in which I focused on one location. In this case, the location is the National Mall, a space that plays a significant role in shaping our mainstream sense of American identity. The National Mall is the commemorative epicenter of the country, and I see this project as another look at how American patriotism and identity are cultivated. I tackle these same issues in National Trust through depicting institutional architecture, the media, and political campaign events, while in The Mall I take a step away from these noisy, flashy spectacles.

I wanted to make pictures that are understated. Even though the main landmarks on the Mall occasionally appear in the pictures, most of the images are anonymous, depopulated, and dark. At first glance they may not appear as politically charged as the National Trust pictures, but they are still political in nature. Let’s face it: the Mall perpetuates propaganda, and a main objective of this project was resisting this notion of the Mall as a place that holds absolute truths for all people. Sometimes I get tired of all this empty idealism when there is so much that is still blatantly wrong with our country and the world at large. So in many cases I’ve turned my camera away from what we’re supposed to pay attention to and toward things that are damaged and seemingly inconsequential. This work comes from a place of disillusionment, but I also think that the fact that I am willing to live in the capital and to engage with its iconic spaces signals that I do feel attached to the U.S. While things are very bleak right now, of course I hope that things do improve for us and the rest of the world, and not just for the 1% of the 1%.

© Jay Turner Frey Seawell from The Mall

© Jay Turner Frey Seawell from National Trust

Feinstein: You recently received the 2016 Award for Innovation in the Documentary Arts from the Archive of Documentary Arts at Duke University for this work. This, like much of your work, seems to go beyond a traditional understanding of "documentary" -- would you agree?

Seawell: At the end of the day “documentary” is merely a category that doesn’t have a fixed meaning, like the other labels that are imposed on photography. There are so many ways to challenge our understanding of documentary, and I am fascinated by the ways in which photographers expand the conversation of what documentary can be. Some methods can be overt, like Richard Mosse’s use of infrared film to document war in the Congo. He’s very much engaging with the outside world, but the pictures, with their surreal color palettes, depart from older war pictures that we might describe as “traditional.” Then there are more subtle ways. Photography is such an explicit medium. The camera points and says “Look at this!” How do you make pictures that simultaneously point to something but also deal in symbolism and function like figurative language in writing? How can pictures hint at societal and political issues by exploring what’s bubbling beneath the surface? In particular I think of Paul Graham’s photography. I think about these questions and I try to be conscious of how my work fits in with the continuum of documentary photography practices.

© Jay Turner Frey Seawell from National Trust

© Jay Turner Frey Seawell from National Trust

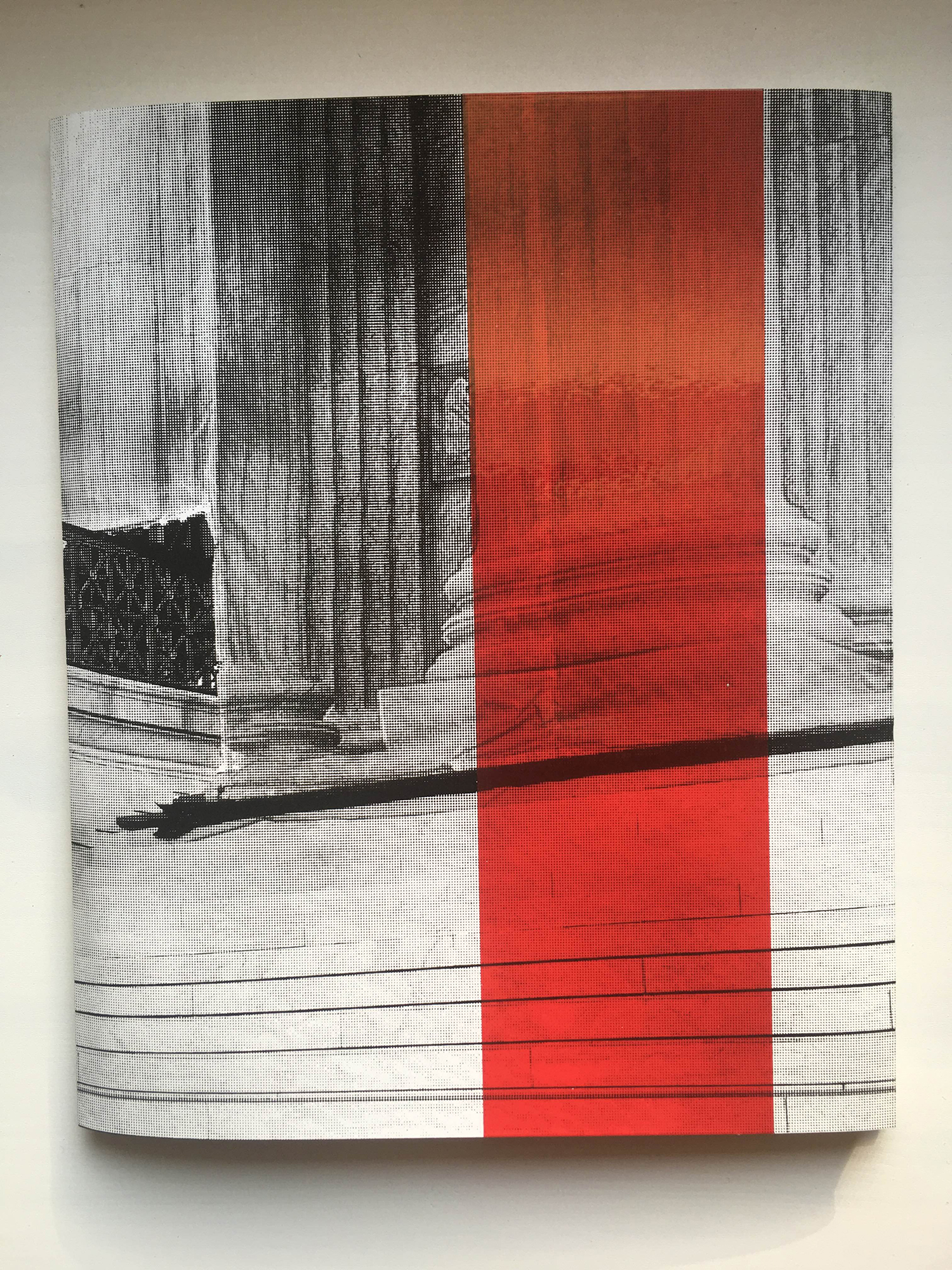

Feinstein: There's an image of the Supreme Court towards the center of the book -- it looks like there's a facade/ fake backdrop hanging above the steps. What's going on here?

Seawell: When I was still in grad school in Chicago I came to DC for Obama’s second inauguration in January 2013. At the time, the Supreme Court building was undergoing renovations and during these renovations there was a gigantic, lifesize image of the façade that had been printed and placed in front of the building. So this picture of the Supreme Court building is an image of a façade - an image of an image. It felt very appropriate given that this project is so much about surface appearances and façades.

Feinstein: The image also appears on the cover, in black and white, with a transparent red bar placed over it. What's behind this, graphically and metaphorically?

Seawell: My editors at Skylark Editions made that decision, and I got the sense that they placed the red bar on the cover mainly for aesthetic reasons. They felt like the cover needed to be energized somehow, and I agree. When I see the red bar, I think about how red can signal alarm.

Feinstein: As many of the images have a 'behind the scenes' feel, were you gaining special/ press access?

Seawell: I used to work as a photojournalist and I did have some experience photographing political events with press access before going to grad school for my MFA. I drew on those experiences while working on “National Trust,” but I was no longer working as a member of the press. It was actually amazing how freely I could roam at political rallies in 2012. All I had to do was go through airport-type security and then once I was in nobody ever questioned me about what I was doing or what I was photographing.

There are two exceptions: I did have to get special access to make the picture of Harry Reid at his press conference, the first picture in the book. A friend of mine had a press pass to the U.S. Capitol building and he generously got me in to photograph for a bit. There’s also a picture of a deep blue curtain with the shadows of media members cast onto the curtain, and that was made at Obama’s 2012 election night rally in Chicago. That was a ticketed event, and I went to McCormick Place without a ticket. While walking there I struck up a conversation with a group of people who had a no-show in their group and they graciously gave me the ticket. Pure luck.

© Jay Turner Frey Seawell from National Trust

Feinstein: How do you see National Trust speaking to your other bodies of work, or your larger artistic practice?

Seawell: A critical word here is “history.” When I was growing up my parents made sure that learning about history was a significant part of my upbringing. As I grew older I became interested in how history is written and reinterpreted. The project that I made before grad school was about British people who re-enact the American Civil War. National Trust stemmed from my interest in classical-style architecture and its references to ancient empires. And although the political events I photographed were about “current events” as I was making them, they inevitably became history. Everything does. The Mall looks at a space where history is written, carved, and presented in a highly selective manner. As citizens, we’re always grappling with the intersection of the past and the present.

Feinstein: This is always a dreaded interview closer, but I know you've got something in the works. 'What's next, Mr. Seawell?'

Seawell: Since National Trust was published, I have continued to work on my project The Mall and I am currently working on translating this work into book form. I am also working on a project that involves photographing in France. For logistical reasons, I can't photograph that often for this project but I did go to France last summer and I'm going again this July. The work explores relationships among me, my father, his death, and his interest in the history of World War II.

© Jay Turner Frey Seawell from National Trust

© Jay Turner Frey Seawell from National Trust

© Jay Turner Frey Seawell from National Trust

© Jay Turner Frey Seawell from National Trust

BIO

Jay Turner Frey Seawell is a photographer based in Washington, DC. He earned his MFA in Photography from Columbia College Chicago in 2013. His photographs have been included in numerous exhibitions in the United States as well as the Pingyao International Photography Festival in China. Seawell is a two-time nominee of The Baum Award for An Emerging American Photographer (2014 and 2016). His work is in the permanent collections of the Museum of Contemporary Photography and the Archive of Documentary Arts at Duke University. His photographs have appeared in various publications including VICE Magazine and Bloomberg Businessweek. Seawell is the 2016 recipient of the Award for Innovation in the Documentary Arts from the Archive of Documentary Arts at Duke University. His first photobook National Trust was published by Skylark Editions in 2016.