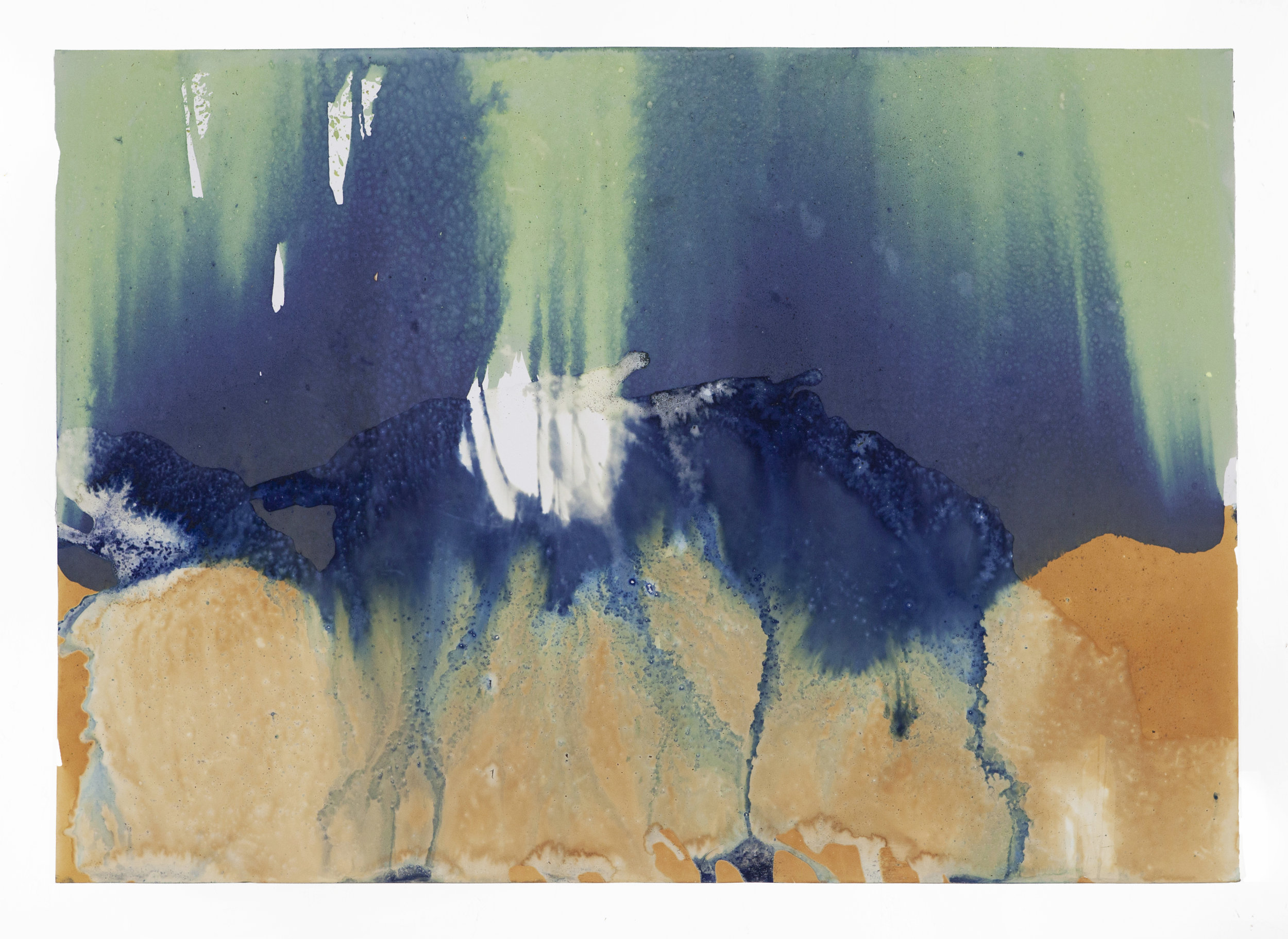

Photo © Meghann Riepenhoff

Rebecca Solnit has become one of the most influential writers, historians, and activists of the past decade. Her 2014 collection of essays Men Explain Things To Me undoubtedly influenced the popular use of the term "mansplaining," and A Field Guide to Getting Lost and numerous other writings have received ongoing acclaim and feel increasingly relevant in today's tense political climate.

Beyond her literary and political influence, Solnit's writings have made a mark in the photography community, with photographers, educators, curators, and critics alike citing her influence. On the heels of Solnit's recent publication, The Mother of All Questions, we contacted some of our favorite photographers and other pillars of the photography community to learn how Solnit has impacted their work and ideas about the nature of "seeing." Many have included some of their favorite Solnit quotes as well.

Photo © Meghann Riepenhoff

Meghann Riepenhoff Photographer/ Artist:

"The strange resonant word 'instar' describes the stage between two successive molts, for as it grows, a caterpillar...splits its skin again and again, each stage an instar. It remains a caterpillar as it goes through these molts, but no longer one in the same skin...Instar implies something both celestial and ingrown, something heavenly and disastrous, and perhaps change is commonly like that, a buried star, oscillating between near and far." - Rebecca Solnit

A Field Guide to Getting Lost was a revelation for me. When I read this passage, I knew the title for my series was Instar. Solnit’s description of this biological process felt like poetry, and it so elegantly wove together the beauty, chaos, truth, and pain of transformation. Her use of language, the ability to integrate such a complex palette of ideas, and the encompassing nature of her inquiry imprinted on me.

For many years, I have been moved by the blue at the far edge of what can be seen, that color of horizons, of remote mountain ranges, of anything far away. The color of that distance is the color of an emotion, the color of solitude and desire, the color of there seen from here, the color of where you are not.

Some of my earliest memories include the color blue: a blue satin blanket, the deep luminous blue of stained glass windows, the blurry blue kaleidoscope of eyes open underwater, the way the entire world around me looked blue just before darkness. Solnit’s The Blue of Distance encapsulated and evoked so many of the ways the color impacted me personally, and also pointed to the more universal mystery of the color that is our sky, our deep seas, our unknown.

The truth is that these two passages revealed something to me that shifted my soul, and then embedded in my work. The poignant experience of reading these words taught me about how I wanted my work to operate, to feel, to provoke, and to last.

Photo: Delaney Allen

Delaney Allen Photographer

As I began the untitled project (later titled Getting Lost), my mental space, as well as the desire to further my editing process when creating, led me to expand beyond personal writings and include those ideas from outside sources. With that, I remembered Solnit’s A Field Guide To Getting Lost and went back to it rereading the work in a handful of sittings. It had previously spoken to me but now was now what I was desiring both mentally and creatively. Eventually, I allowed for further investigation of my series and loosely based some around passages from her writing. That particular book allowed me to work through issues at hand and translate said concerns into imagery.

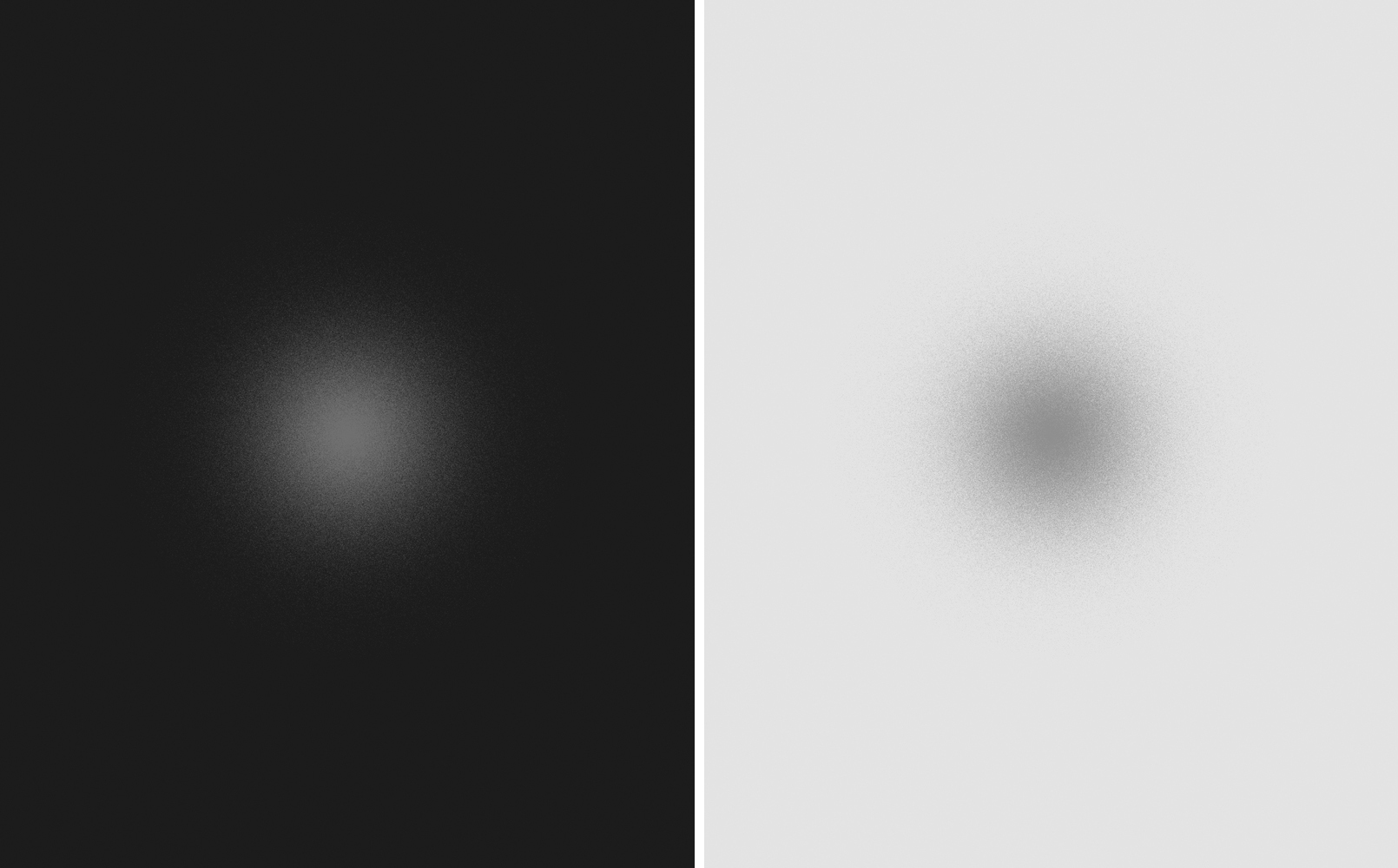

Photo © Brea Souders

Brea Souders Photographer.

Rebecca Solnit’s A Field Guide to Getting Lost is a book that I’ve held close for years. “The Blue of Distance” chapters must have inspired my work Royal Blue even if I wasn’t consciously aware of it at the time. Royal Blue was built out of the same kind of longing that she describes in these chapters. She writes:

“If you can look across the distance without wanting to close it up, if you can own your longing in the same way that you own the beauty of that blue that can never be possessed? For something of this longing will, like the blue of distance, only be relocated, not assuaged, by the acquisition and arrival, just as the mountains cease to be blue when you arrive among them and the blue instead tints the next beyond.”

Photograph of Sarah Lewis © Stephanie B. Mitchell

Sarah Lewis Assistant Professor. Departments of History of Art and Architecture and African and African American Studies, Harvard University

Rebecca Solnit has a visionary intellect. She is at once both a seeker and a scholar. The same mind and heart that could write A Field Guide to Getting Lost — a book that offers invaluable sustenance for creative journeys — could also write River of Shadows — an irreplaceable text for understanding the history of photography and the intersection of art and technology among other themes. What’s more is that Rebecca is also, it seems, indefatigable, constantly producing, constantly writing, and always reminding us that the work is journey, one requires that we all, joyfully, and with all of facets of ourselves, rigorously do our part. I could not admire her more.

Photo © Orestes Gonzalez

Orestes Gonzalez, Photographer.

I read Rebecca Solnit's memoir The Faraway Nearby in 2013. It influenced my storytelling style of showing what is meaningful to me based on my own personal history.

Being a Baby Boomer, I've embraced chronicling faded institutions that I grew up believing were infallible. Among them: The Decline of American Industry, The Destruction of Landmarks/Landscapes in our culture,the Faded Cuban Revolution.These are three subjects that keep me motivated and that I personally identify with.

Here’s a one of my favorite quotes from her book:

“Stories are compasses and architecture; we navigate by them, we build our sanctuaries and our prisons out of them, and to be without a story is to be lost in the vastness of a world that spreads in all directions like arctic tundra or sea ice.”

She reinforced my identity.

Photo © Yael Eban

Yael Eban Photographer

Each time I read Solnit’s essay, The Blue of Distance, I think about my unrelenting desire to capture the most paradoxical of colors in the landscape. I am reminded of Roland Barthes’ assertion that it is not painting but photography that signifies the human “having-been-there.” The constraint of physical presence is unique to photography, for a painter can paint a landscape without seeing it in real life. We are in the golden era of the screen, each of us navigating the other’s photographed experiences from the comfort of our hand-held devices. Social media capitalizes on our unwavering belief in photography’s indexical relationship with reality. Our innate desire for what we can’t have - the faraway - manifests itself as a fear of missing out. Perhaps we can divorce the superimposition of desire and reality and do as Solnit suggests in the passage below – cherish the blues of longing while attempting to be truly present.

Solnit: “We treat desire as a problem to be solved, address what desire is for and focus on that something and how to acquire it rather than on the nature and the sensation of desire, though often it is the distance between us and the object of desire that fills the space in between with the blue of longing. I wonder sometimes whether with a slight adjustment of perspective it could be cherished as a sensation on its own terms, since it is as inherent to the human condition as blue is to distance? If you can look across the distance without wanting to close it up, if you can own your longing in the same way that you own the beauty of that blue that can never be possessed? For something of this longing will, like the blue of distance, only be relocated, not assuaged, by acquisition and arrival, just as the mountains cease to be blue when you arrive among them and the blue instead tints the next beyond.”

Photo © Danielle Ezzo

Danielle Ezzo Photographer

Rebecca Solnit doesn't just influence my art practice. To say that would be a disservice, as she's inspired me to really tap into how I see and process the world at large; it's a personal philosophy. It started with A Field Guide to Getting Lost six years ago, but continues today with everything she writes because she has the unique power to articulate that which is unarticulated, to focus in through the lens of what it means to be human.

Roula Seikaly

Roula Seikaly Independent curator and writer

"In the spring of 1872 a man photographed a horse. The resulting photograph does not survive, but from this first encounter of a camera-bearing man with a fast-moving horse sprang a series of increasingly successful experiments that produced thousands of extant images. The photographs are well known, but they are most significant as the bridge to a new art that would transform the world." RS

Opening sentences are, without exception, the hardest to craft. Anyone who has ever written anything knows this as truth. When I revisited Rebecca Solnit's River of Shadows: Eadweard Muybridge and the Technological Wild West for this project, I marveled at how economically the introductory passage (technically three sentences) summarizes the wide-ranging issues she connects in this volume. Solnit could and does write about anything, as her breadth of publications suggest. As a reader and writer, I feel so fortunate that she regularly turns her incisive mind to photography. She broadens the critical dialogue, and encourages all of us to look closer and think harder about image culture.

Rafael Soldi Photographer, Curator, co-founder: Strange Fire Collective

When I started working on Life Stand Still Here, I had begun reading Virginia Wolf and I knew there was a connection there. I was captured by the way Woolf dwelled in darkness, and how she led us to discover her characters' inner, deepest selves. I struggled for a long while to put this into words, I could only feel it in a visceral way. Then I stumbled upon a brilliant essay by Rebecca Solnit on The New Yorker, Woolf's Darkness: Embracing the Inexplicable. Solnit's words described in vivid color all that I had been feeling in regards to Woolf's 'language of nuance and ambiguity and speculation,' as Solnit puts it. Solnit was incredibly helpful in studying and understanding Virginia Woolf's mysterious psyche and bringing darkness into words. A few months later, The New Yorker posted a second essay, this time by Joshua Rothman, which was also excellent and addressed Virginia Woolf's idea of darkness and privacy. Both analysis of Woolf were extremely influential to me.

Matthew Gamber Photographer

I was drawn to Solnit's writing in an essay written for the New Yorker in 2014, Woolf's Darkness: Embracing the Inexplicable, an adaptation of a chapter from Men Explain Things to Me, where she had written on Virginia Woolf using words as a way to explore ambiguity as liberty:

“There is a kind of counter-criticism that seeks to expand the work of art, by connecting it, opening up its meanings, inviting in the possibilities. A great work of criticism can liberate a work of art, to be seen fully, to remain alive, to engage in a conversation that will not ever end but will instead keep feeding the imagination. Not against interpretation, but against confinement, against the killing of the spirit. Such criticism is itself great art.”

In reflecting on the confining peculiarities of art criticism, Solnit reflects on Woolf’s descriptive capacities as a way to enhance the spirit of another’s work. Criticism can become narrowly restrictive for the sake of categorization, only creating a sense of accomplishment for the categorizer. In writing critically of another's work, the critic risks falling into the terrible trap of mistaking monologue for revelation, or worse, connoisseurship for appreciation. On another level, I found that by following Solnit's example of counter-criticism to illuminate the work of our colleagues, we foster a more meaningful connection with the collective audiences we share. As we search for precision through our words, we have the license to seek the companionship of the thoughts we admire in our own contemporaries.

Photo © Magali Duzant

Magali Duzant Photographer

In many aspects Rebecca Solnit’s writing has taken on something so natural as to seem inherently there in my world view. My recent work, In Waiting, The Sea, is a series of long duration cyanotypes of the ocean exposed ( from days to weeks ) via slide projection within gallery or studio spaces creating a translation rather than a reproduction of the original image. In The Blue of Distance from A Field Guide to Getting Lost, Solnit writes of the blue at the horizon and the light that gets lost and on into desire as a sensation worth as much if not more than the longed for object. I have read nearly everything she has written and had marked this particular section up years ago, underlining and connecting thoughts and yet it wasn’t until an artist couple sent a PDF of this exact section to me recently that I realized just how much it had permeated my thoughts, my working practice. In writing of the cyanotypes previously I had referenced blue as a sensation, time as an experience, Iris Murdoch and Paul Valery, the death of an image for the birth of a new one, and yet on reflection the piece was really a direct response to this blue distance, this sensation that desiring that far off vista or coming image can be an answer in and of itself.

Photo © Dawoud Bey

Dawoud Bey Photographer

Rebecca Solnit's writings compel us to a deeper appreciation of place. Her writings reveal place as both a complex personal experience that is also an ever evolving and deliberate social construct. Her writings on the ways in which gentrification is reshaping the social landscape and experience of San Francisco informs my own visualization--in my Harlem Redux photographs--of the ways that the Harlem, NY community is also being reshaped through these forces.

- Dawoud Bey Photographer.

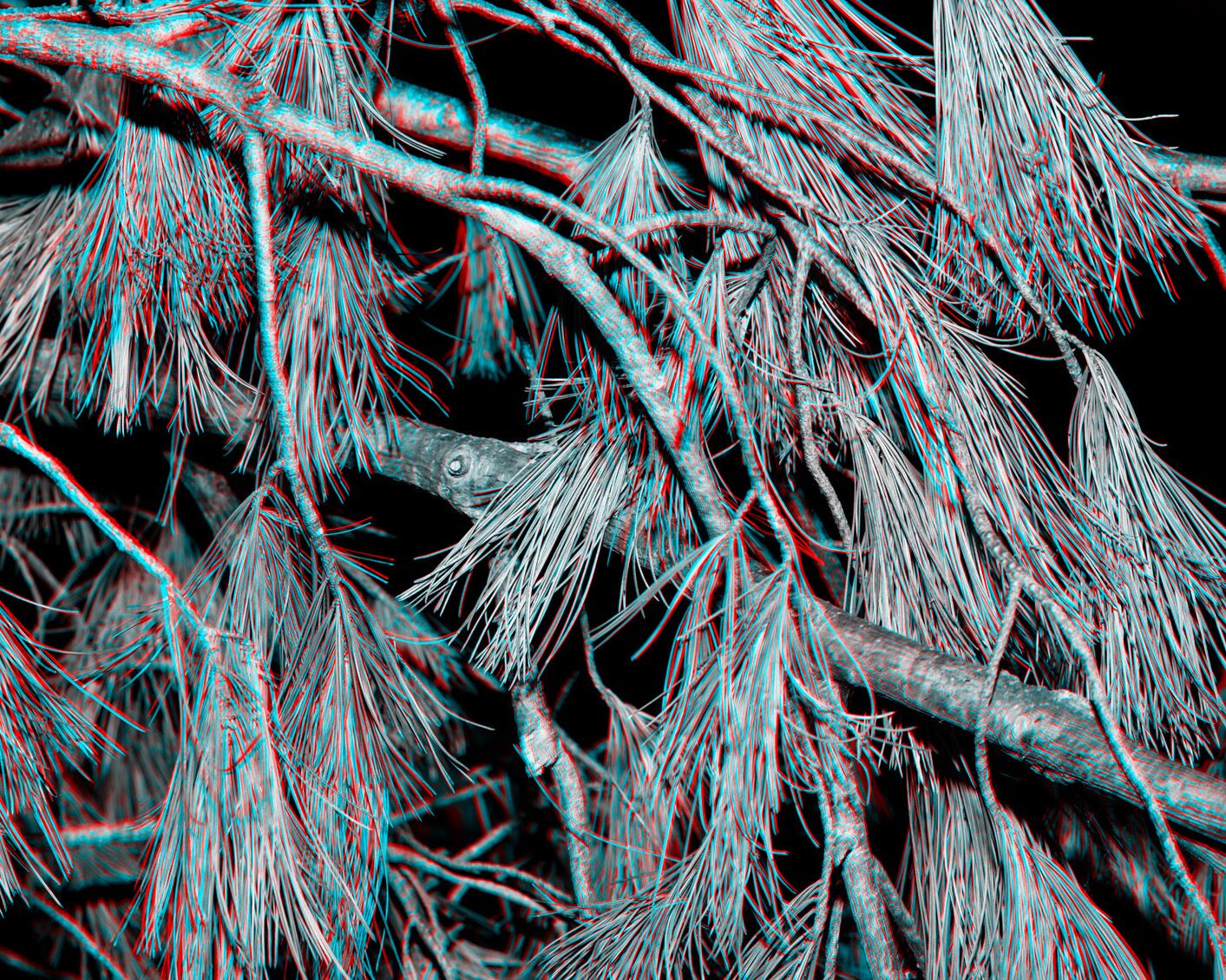

Photos © Serrah Russell

Serrah Russell Photographer, Curator @ Vignettes. Art Director @ Prints.ly

Reading Rebecca Solnit touches me the same way as encountering a work of art by another artist that I wish I had created myself. That moment does not come from jealousy or envy but instead, it is the breath of relief, the satisfaction internally of being understood, of remembering that you are not alone.

Her writings have given a voice and a language to what I am working towards in my visual art practice. To me, she has always been the voice of artists. We need these voices so badly. To have someone writing about art, for art.

Her book of essays As Eve Said To The Serpent: On Landscape, Gender and Art revealed to me how my work was inherently feminist and arose from a history of women who have been considering and contemplating the body within the landscape, the subject as influenced by its surrounding. A line of hers from Men Explain Things To Me says - 'A woman both exists and is obliterated.' and has become a touch point for my ongoing photographic series A Woman Is Always An Island.

My current work in the group exhibition Future Potential of Dreams is opening April 29th in Los Angeles at Gallery Clu and certainly gains inspiration from Solnit's writing. We are three female photographers, using art as a means of investigating our experience in the surrounding landscape, both wild and term.

We all connect strongly to this quote from A Field Guide To Getting Lost -

"The places are what remain, are what you can possess, are what is immortal. They become the tangible landscape of memory, the places that made you, and in some way you too become them. They are what you can possess and what in the end possesses you."

Image of Andy Adams © Brunna Borges

Andy Adams. Founder, FlakPhoto

The best writers are fun to read and make you think. If you’re lucky, they challenge your worldview and show you something new about the way things are. Rebecca Solnit does all of this in spades. And she does it every time. One of my hobbies is reading books aloud to my wife. Sure, it’s nerdy but it’s also extremely pleasurable and, in this case, necessary to really appreciate the breadth and depth of the writer’s vision. The best part about reading together is discussing what we’ve just experienced. Solnit’s books are dense with ideas and passion and insight. Her essays are so eloquently spun—so expertly crafted—they benefit from a verbal expression and a post-read conversation. I’m glad we can share these experiences together. And I’m grateful that someone is out there in the world advocating for justice and beauty and understanding. Rebecca Solnit reminds me there’s hope even when things feel dark and impossible. She’s a beacon of brilliance, progressive thinking, and optimism. She’s a national treasure and she’s showing us all the way forward.

Photo © Shane Lavalette

Shane Lavalette Photographer, Director - Light Work

Solnit's writing has always resonated with me, for her lovely use of words and the potency of the ideas she sheds light on. Reading Wanderlust as a student undoubtedly informed my approach to photographing, at a time in which I was really learning to think through pictures. I recall trying very hard to find ways to become more present while making images out in the world and I think the simple practice of walking and careful looking (without a camera) was an important step to being more sensitive to my surroundings. One of my favorite quotes is below:

“Walkers are 'practitioners of the city,' for the city is made to be walked. A city is a language, a repository of possibilities, and walking is the act of speaking that language, of selecting from those possibilities. Just as language limits what can be said, architecture limits where one can walk, but the walker invents other ways to go.” - Rebecca Solnit, from Wanderlust: A History of Walking

Photo © Jill Greenberg

Jill Greenberg Photographer + Filmmaker

I love Solnit's Men Explain Things To Me, and I think much of my own work has connections to many of Solnit's ideas. When I was in school, my thesis project, The Female Object, 1989, which was a multi-track recording which I sound engineered, voiced, photographed, along with mural images installed in a black box gallery, was about the internalized panoptical male gaze which had (has) taken root within the consciousness of the modern woman. I tend to get inspired by nonfiction, big ideas, and they just percolate until something grabs me, since it can be very hard to engineer and image with such a didactic message. It is especially hard to make images critiquing the objectification of women, even taking into account the leeway I might have as a female photographer.

For the past 8 or so years, since I began my Glass Ceiling series in 2009, I have returned to my feminist foundations. That series was done before it became au courant to be a feminist, but it has been both positive and negative to have these issues become so relevant again. As a young artist in the 80s, I was learning about feminist theory and the semiotics of image making at RISD, classes such as "Discourse on Pornography" and by way of one class I took at Brown, with the illustrious Mary Anne Doane. It is great that we are all discussing the male gaze and female objectification (again) but I wonder if there is any hope of moving the needle towards parity. Maybe in 100 years?

Photo © Rebecca Najdowski

Rebecca Najdowski Photographer

Rebecca Solnit’s lucid meanderings through the material, philosophical, social, and political dimensions of land (particularly the southwest and California) have provided a way to think through ideas around nature and our relationship to it. Her writing is deeply perceptive and reveals landscape to be a multifaceted environment of human and non-human making. Attuning to this has inspired me to think and make critically in my own practice that deals with landscape photography. Solnit’s writing has prompted me to examine what it means to make photographs about nature by considering how myth direct experience, and the matter of landscape itself are entangled.