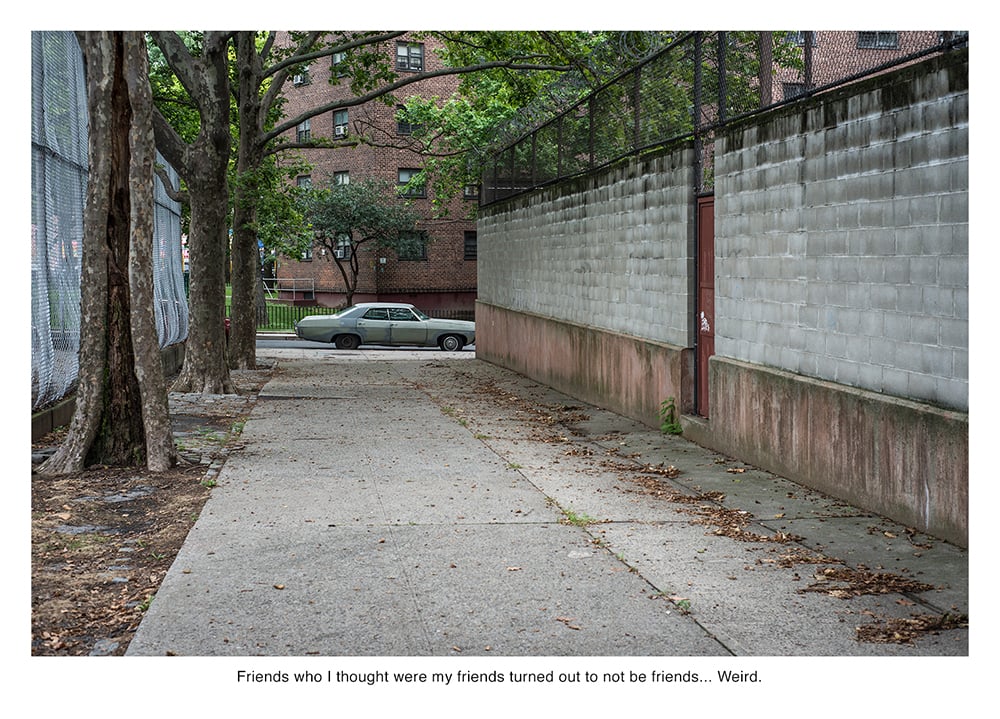

In 2007, photographers Nate Larson and Marni Shindelman began Geolocation, a nationwide project, tracking the locations of hundreds of tweets from around the United States, Canada and the UK and making photographs to mark their location in the real world. Working long distance, the photographers' collaborative process explores the massive, rapid collection of often incredibly personal data, grounding it in physical form. The images, ranging from roadside slices of America not unlike Sternfeld's America Prospects, to lonely, unspecific landscapes, give a heartbreaking window into contemporary isolation and the need to connect in a time in which everyone is at our fingertips. The culmination of their work was recently pared down to a wonderful publication of more than 70 photos published by Jennifer Schwartz and David Bram's Flash Powder Projects, and includes essays by Julia Dolan, Kate Palmer Albers, Jamie Allen, Chad Alligood, Mark Alice Durant, Paul Soulellis, Michael Wolf and Natalie Zelt. We spent some time (virtually, of course) with Marni and Nate over email to learn more about their work and its implications.

Jon Feinstein / Humble: What prompted you to start this project?

Marni Shindelman: Nate and I had worked on projects about distance for a few years before starting Geolocation. We were photographing a project where we were translating text messages via semaphore flags across small distances, when we came upon a small Yahoo! mashup that gave us tweets and coordinates of where they were sent. We were in the center of the financial district in Chicago holding this printout with this tweet and made a photograph where the tweet was send. We both realized this was important, and thankfully technology caught up with us very quickly after that and we discovered more and more tweets that were geolocated.

Have you collaborated before? How did you come to making work together?

MS: Nate and I met multiple times at various SPE (Society for Photographic Education) conference. In 2007, after a late evening in Miami, we casually agreed to collaborate on something. In 2008 we exhibited Witness, our first project together, where we photographically tested our psychic abilities.

Nate Larson: In summer 2007, I did a residency at Visual Studies Workshop in Rochester, where Marni was living at the time. We had been talking about making something together and sending a bunch of mail art back and forth, so being in the same city for a month helped it all come together. We made a trip to Lilly Dale, a community of psychics in western NY and took a class in how to have an out of body experience. It was pretty absurd but it gave us a jumping off place and more than eight years later, we’re still making things together.

Can you tell me a bit about your collaboration process?

MS: For years my father would tell me that Nate and I were “just like McCartney & Lennon”, and I’d shrug it off as just my dad’s attempts at trying to understand what I do. Then the Atlantc did a whole issue on genius and creativity (hilarious that this was an issue on genius. . . ) and they had an article “The Power of Two” about John Lennon and Paul McCartney’s process for writing. And it was exactly how Nate and I work. Most people think collaboration is about sitting right next to each other working, for us being behind the camera together, or sharing a desk. This couldn’t be farther from how we work. We work in a ping pong fashion, where we send ideas back and forth between each other. We utilize every digital platform– Dropbox, GoogleDocs, Facetime, Slack.

When we are on residency, I wake up around 7:30 am to find my night owl collaborator has filled a board with articles and post it notes. I rearrange the notes, write more post its, then go out and photograph and go back to sleep around noon. Nate thinks best starting around 8:30 pm. I am best from 8:30 am - 3:30. But what works so well is this healthy competition and game we play where we are completely open about ideas. Collaborating for me is like whispering your most embarrassing secrets or habits or obsessions to your friend. It’s the things I pick up on while reading and stew on for weeks and then share with Nate and then he takes those ideas and runs with them. Then sends them back to me. Our work is driven by a methodology that we both work on in this fashion. Then we go out as if we are on assignment and make images, sometimes together, but often apart.

Why Twitter over Instagram or another app that allows for geolocation?

MS: Simply, Twitter is inherently public. Twitter is being archived by the Library of Congress, as a historical timeline. Instagram started a year after we began this project, and it took even longer for the GPS tagging of images to become a trend. We’ve toyed with ideas of Instagram, but that project would become more about recreating a view project than memorializing a text or a thought.

NL: The public timeline has been really important for us, which doesn’t work in quite the same public way on Instagram and Facebook. However, a good number of tweets that we have worked with have been aggregated from other platforms, for instance reposting from a user’s Instagram to their Twitter.

In final form, these are anonymous to the original tweets' authors. Why this decision?

MS: The main reason for this decision is that the username change the entire tone of a tweet. A tragically sad tweet may come from the most flip or vulgar Twitter handle. They aren’t anonymous, just obfuscated. If you type in the exact text of the tweet, the user and all information will appear.

NL: As Marni mentioned, the information can be found, but it felt like it shouldn’t be on us to call someone out. It felt too close to doxing, which is something that we’re not interested in. By omitting the user name, it can focus on the emotion or thought, rather than the person themselves.

Are any of the original authors of the tweets familiar with the work?

NL: We have not had any of the original users get in touch directly, which surprised us a bit. Especially after some of the public art iterations that had a much bigger audience than a gallery would. The closest that we’ve come is talking to neighbors and even family members, which is usually quite nice. In England, a neighbor invited us in for tea after we chatted about the project, and we had a lovely conversation about photography and photography in public spaces. When we were photographing at the Indianapolis International Airport, the gate attendants got used to seeing us with our cameras and would always ask if we were getting good images. I ended up showing them some of the photographs, which was really nice for them to see their workspace in a different way.

Do you see Geolocation being in dialog with Doug Rickard's Google-Street-View work?

NL: We like Doug’s work a lot and Marni spoke about our work on a panel with Doug at a conference. I’ve always thought about Doug’s work as a portrait of a city / community at a very particular time of post-industrialization. We see our work as being more directly reflective of individuals in the singular, but when we do a site-specific project in a city, I think that it brings us closer together in the notion of mapping a community and looking at everyday life in public spaces.

With regard to GSV and mapping, we’re also very influenced by Mishka Henner, and were fortunate to do a two-person show with him at Blue Sky a few years back. We thought it was a great pairing, our Geolocation with his No Man’s Land. I also like his newer Feedlots and Oil Fields a lot.

Other influences include Trevor Paglen, Jill Magid, LOCA, Hasan Elahi, Mark Klett & Byron Wolfe, Joel Sternfeld, Penelope Umbrico, Michael Wolf, Kate Palmer Albers, and James Brindle, among others.

Where do you both fit personally into all of this?

MS: I think Twitter is inherently sad, not just the tragic tweets about death or #RIP, but the sheer volume of people longing to be heard is what crushes me. When we’re working on a set of images, I’m reading Twitter from a hyperlocal perspective for a few weeks. While only a few tweets actually break my heart, the chatter of individuals is overwhelming. I do tend to ignore the tweets obviously from bots, but they are getting louder and harder to ignore. I personally use Twitter like a newspaper. I keep my feed very curated and only read it to find out things like what my favorite author is reading, or small bits of information like that.

In some of your writing about the project, you've used the term "ephemeral online data." What's this all about?

NL: We frequently use the metaphor of a river to talk about the timeline on Twitter, like water, it looks similar but is never the same twice. If you see something, you see it, and if you don’t, it washes away in the river of data. The quantity of data on the internet is of a size that is incomprehensible at human scale and things vanish quickly as we post more and more. We see our role as preserving small moments by reconnecting them to place, plucking tiny data points out of the river and bearing witness to them.

How do you decide that a tweet is worthy of inclusion/ visual pursuit?

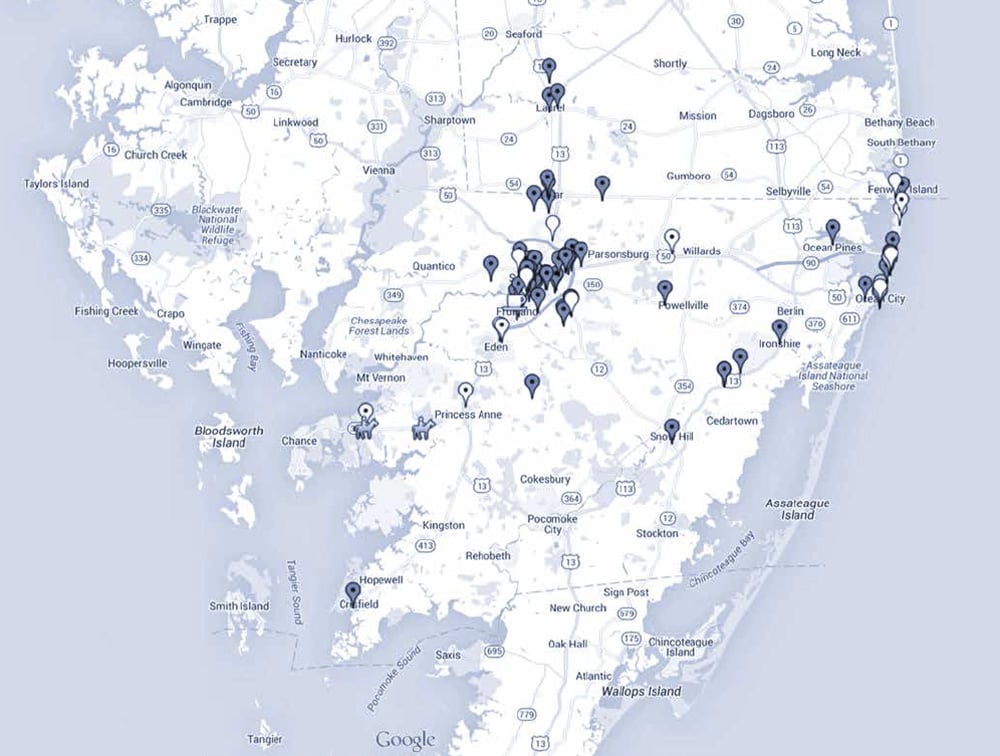

NL: Frequently, we don’t know until we shoot it. When we do a site-specific project, we usually mark around 100 tweets in our working map, and then choose ones to photograph. Sometimes the tweet seems dumb but the location enhances it. And sometimes the opposite happens. We usually photograph around 30 locations culled from the 100 tweets.

In total, over the last 7 years, we’ve shot about 850 photographs for the project, which get edited down depending on the context. 78 of them are included in the book.

If there were a soundtrack to Geolocation, who would be on it?

MS: I must first confess that I just made a 1998 Darkroom Playlist, so my mind is there these days. But I’d have to go with 2 songs. First is Radiohead– Fake Plastic Trees. The second would be Songs: Ohia – RIding With a Ghost. This is one of the best questions we’ve ever been asked, and I’m curious to see what Nate picks.

NL: For me, the soundtrack is all the music we listen to while traveling to make the work. We have a game we play where we try to stick earwigs in the other person’s ear. The top song would have to be the Proclaimers 500 Miles, closely followed by Stevie Nicks White Wing Dove and Europe’s The Final Countdown. And The Blow’s Parenthesis.

I think that Neutral Milk Hotel's In the Aeroplane Over the Sea is the semi-official album of the collaboration, as it’s about the only thing that jointly lifts our spirits on long road trips.

(Editors Note: you can listen to that playlist HERE. Yes. We did.)

Did any of the original tweets include photos?

NL: Yep, sometimes through Twitter and sometimes by aggregation from Instagram to Twitter. We’ve experimented with including them but never really found a way that felt like it worked.

After Ferguson, there were the trending hashtags #IfTheyGunnedMeDown and #IfTheyShotMeDown, where users posted two photographs of themselves in response to the media victim blaming. This moved us quite a lot and we have been thinking about this a lot - perhaps there will be future work that explores this idea.

Bio: Nate Larson and Marni Shindelman began collaborating in summer 2007, working over distance and through site-specific projects. Their solo exhibitions include Pictura Gallery in Indiana, the Orlando Museum of Art in Florida, Light House in Wolverhampton, Blue Sky in Portland, United Photo Industries in Brooklyn, and the Contemporary Arts Center Las Vegas. Selections from their projects have been shown in prestigious museums and art centers in the US and abroad, and they have also received commissions to create site-specific projects all over the world. They were recently artists-in-residence at Light Work and the Robert Rauschenberg Foundation.