Inchworms © Melinda Hurst Frye

Melinda Hurst Frye makes pictures in the dirt. In her latest series, Underneath, worms, caterpillars, beetles, snails and anonymous animal skeletons intermingle with stringy roots and soil that are simultaneously mysterious and hyper real. They at once resemble homages to narrative painting and large scale Natural History museum dioramas, giving a private view into the world beneath our feet. The Seattle-based photographer creates these images in her yard - not with a camera, but with a flatbed scanner, rigging it to a power supply inside her house, and letting its slow, ultra-high resolution scan a landscape rarely explored with such intimacy. In her own words, “The surface is not a border, but an entrance to homes, nurseries, highways and graveyards.” In time for her solo exhibition, up through August at Seattle’s CORE Gallery, we spoke with Hurst Frye about the ideas and process behind this new work.

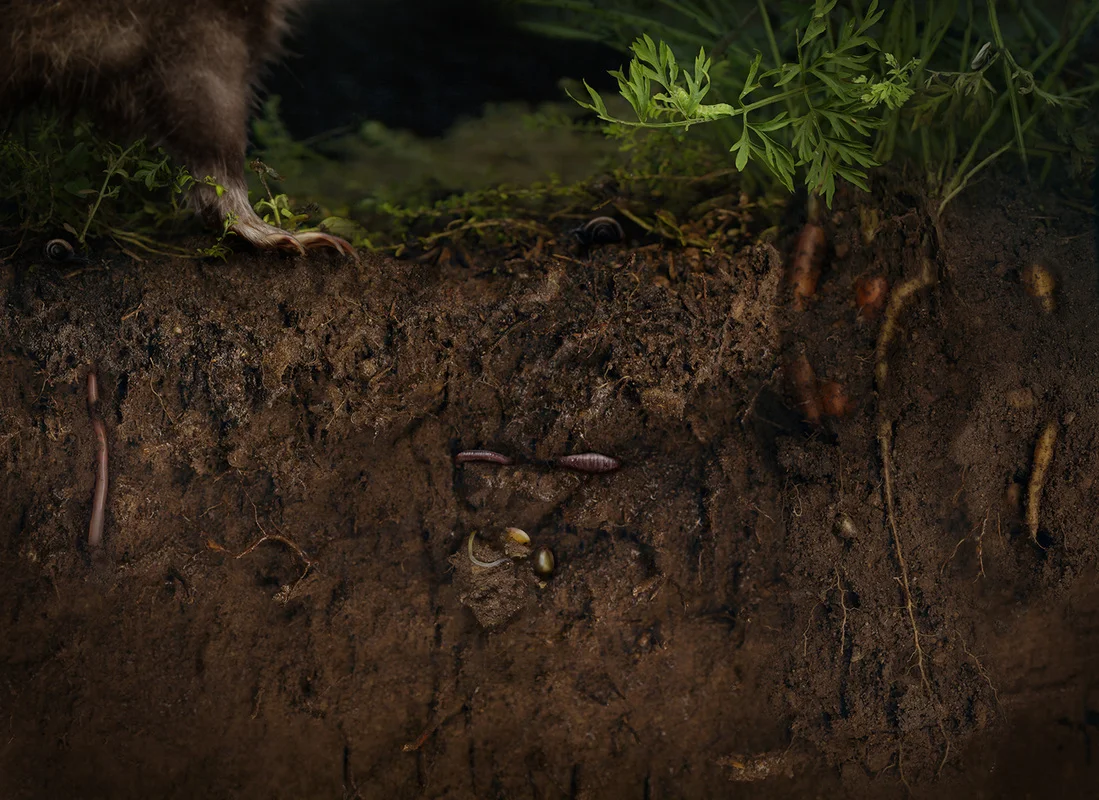

Underneath The Carrots © Melinda Hurst Frye

Jon Feinstein: What was the first image you made for Underneath? How did it all start?

Melinda Hurst Frye: The first image that I formally made for Underneath was Under the Carrots. That was the first image where I intentionally started to make work under this idea of subterranean spaces. Though that image has evolved since I first created it, it has been parted for the elements that I liked, like scrapping scenes in editing a film.

Before that image I had started hunting for bugs and natural elements above ground. I would turn the scanner upside down, but scanners don’t like that (they break), and soon I found that it still only showed me the surface, and I was (and still am) interested in the hidden life. After digging up several of our carrots from our garden and running into worms, and beetles and other critters that I had no idea existed, I thought specifically about the lives and motivations of what's underground. I started to discover the changes in my yard through the day and the seasons, who was present when, what attracted whom, and I wanted to build that narrative.

Underneath The Prunella © Melinda Hurst Frye

JF: Why is the scanner particularly important?

MHF: Process has always been important to my work and practice. I came up as a printmaker, and the process of making something is as important as the final thing that was made. The experimentation and technique influences the final product, and the process is also where the ideas also start popping up. I include the sketching and reading as part of the process, and what materials we choose clearly also influence process.

I used the scanner for several reasons. I felt like it invited play at first, allowing experimentation - which are the roots anyway with the work. Digging in the dirt is a huge pastime in our family, finding worms, planting seeds, burying toys/treasure, so I needed a tool that would let me stay in that playful headspace. The enormous resolution provided detail that I just can’t get with a lens. Aesthetically, there is a lot of mystery that goes with the super shallow depth of field that is unique to the scanner. I didn’t want the work ever to answer any questions about what is happening underground, however to underscore that much is happening underground. The high resolution in the areas that are in focus has always felt surreal and bizarre to me, then it quickly goes out of focus due to the scanner’s shallow depth of field. I wanted that heightened information coupled with the soft hints of what was happening to push the mysterious narrative of tableau. The aesthetics of the scanned image emphasized the idea that I wanted to come across.

Cycycal, Roly Poly © Melinda Hurst Frye

JF: What's the setup look like? How long does it take to make a picture?

MHF: The process is ridiculous, which might be why I am attracted to it. I sketch, I look at what lives in my space, what I want the composition to look like. Then I scan the ground and I populate it with insects or critters based on what the scene is of. Some of the backgrounds are created based on what animal or insect I want to bring in. After I decide where I want to dig (based on which plant has interesting roots, the leaves on the ground or the creatures who are attracted to a specific spot), I dig a hole that’s roughly 5” by 30” and maybe 8-10” deep. Then I bring out the scanner, cards, lights, any insects that I want to scan in the scene rather than bring them in post and maybe sprinkle them in. I use what’s around me, my son’s radio flyer wagon as a table or a plastic beach shovel, or a stick to hold the scanner in place. The scanner needs to stay super still during the 4+ minute scan, otherwise there will be weird artifacts that just don’t retouch out without losing hours of my life. I usually make between 15-30 big scans of each scene. There’s lots of waiting which reminds me of printmaking when the plate is etching in the acid, or even the slow progress of developing film.

After choosing the scan I either photograph who I have found in and around or go through my many photographs of critters. These images come from my collection of finding bugs and beasts, photographing them when I am out, as well as working with collections, such as the Burke Museum, to photograph and scan their specimens. I composite, it is an act of illustration and narrative, not deceit. While they are fabricated, they are also realistic as I try to emphasize the act of looking and discovery. The point of view is distinct and people tend to want to look and find who/what is there, so I was to play with relationships either realistic, or not. Since there are so many species that are still being discovered, we are missing so much information on insects and behaviors that I want some oddity in the narrative of the ecosystem.

Then there is all of the post work, days of postwork, spotting (a scanner in the dirt makes for a terribly dirty file), compositing and some light painting. From start to finish, from sketch to final file, it is usually about 20 to 30 hours. It helps that I like process, I like to work with a scene, and tweak the details for the whole, so this obsessive method works for me.

JF: Were these all made in your own backyard?

MHF: Front yard, specifically. All of the elements had to be from our small Pacific NorthWest area. But it didn’t matter until about halfway through it. At first it was a matter of logistically where I could dig a hole and access power. But location became more important as the idea became more solid. I wanted the mystery of at/below the surface to feel tangible in an urban or suburban space, that life isn’t just us, that these creatures are unseen, communicating and reproducing, and have little need for us. But we have a big need for them. The work is still so new, these ideas are somewhat cloudy still, thanks for following along.

JF: Would you consider venturing elsewhere?

MHF: I do think this work will absolutely continue, and outside of my front yard. There is direct interest for me in what is happening underground and in our environment, however there is metaphor that can be scratched at as well. I am making work about what is not often seen or assumed to in nature, but what about happenings or moments that are unseen? Like in the Duane Michaels of the bar - ‘there are things seen here not in this photograph’. Eventually, I would like to look at the places of events, the idea being that places hold ghosts of us and our happenings. My front yard became my studio, and was at times a little treacherous with shallow holes here and there. I want to continue the series, though I am ready to leave my front yard space. I would love to create scenes from various eco habitats in Washington State from rainforest to desert and through the seasons. Though my next focus is going to be on overwintering and where/how these species spend their time, if they go dormant, or if they lay eggs in the fall, die and let their young carry on. So much of the natural world’s story is about reproduction and survival, I would like to hone in on that. I am not sure what, if any, location rubric I will have for that.

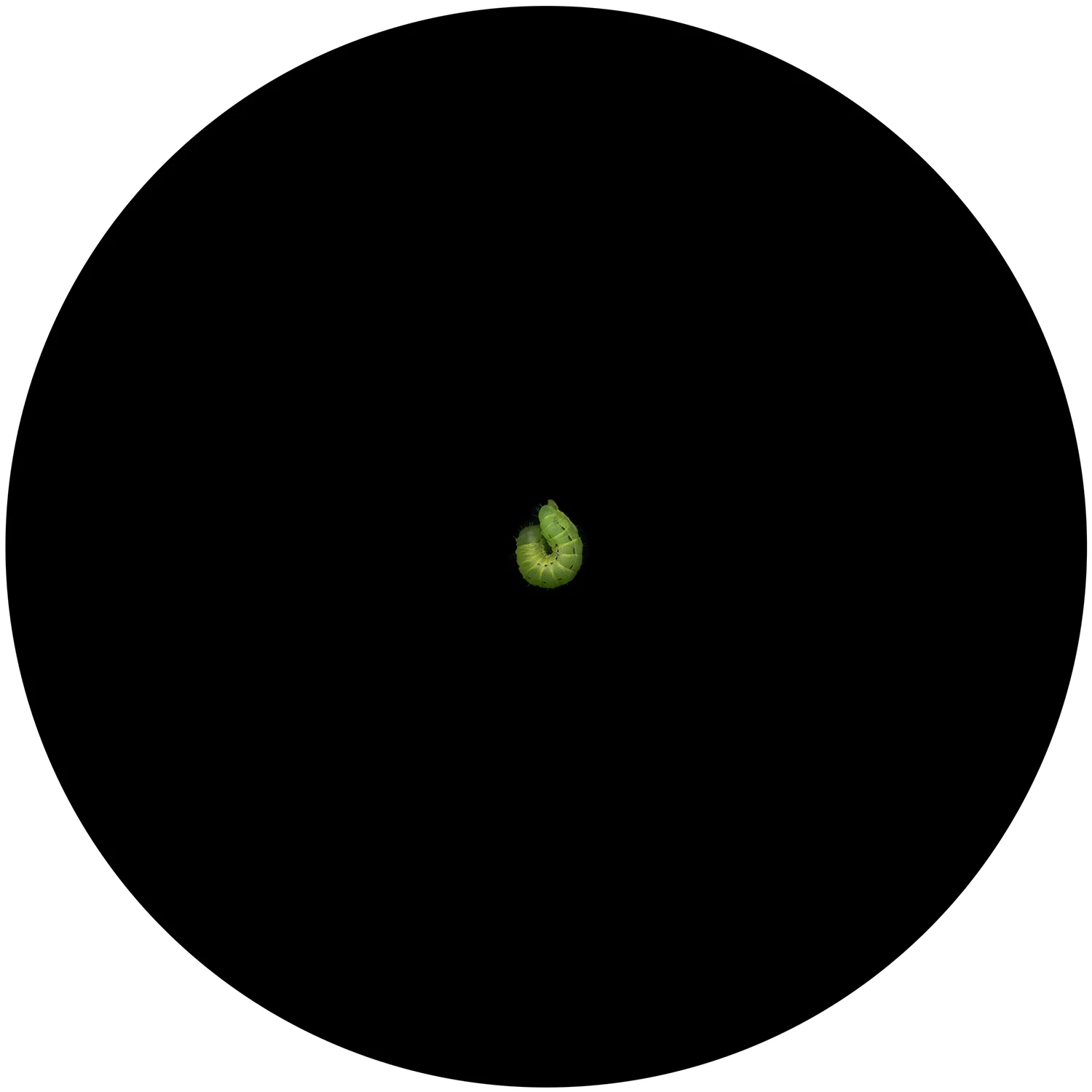

Cyclical, Caterpillar © Melinda Hurst Frye

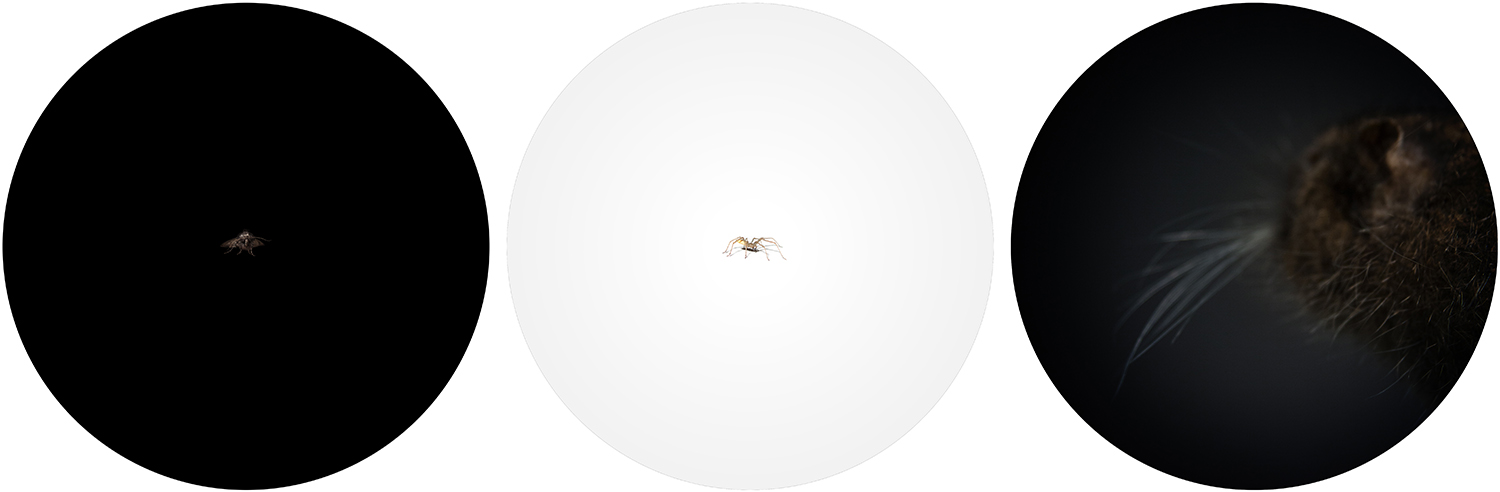

JF: Can you tell me a bit about the distinction between the "landscape" images and the round ones? Do you see the round images as portraits of sorts?

MHF: It started out that I simply wanted to focus in on one element that I was using. The landscapes became to feel too overwhelming and I wanted to compliment the busyness of those scenes (which are very big), with small, more precious objects or portraits. I like that you call them portraits -- that feels right. They are a chance to just observe the small life without the context of the environment. They are a visual break from the bigger images.

JF: I love the caterpillar GIF. have you explored motion further?

MHF: I want to keep working with this story, and I have made some rudimentary gifs. What I would like to do is more intentionally use motion. I think the static scene that just slightly moves can create the sense of surprise (Like Gillian Wearing’s police portrait or what Susie Lee did in her video portraits Also, I would like to use the frame rate to slow the scene way down, I attached just a slow motion night scene of a leaf that I am in love with right now. More of that.

JF: This is one of my favorite questions to ask artists – it’s a recurring curiosity for me: If there was one song soundtrack to this work, what would it be?

MHF: Music doesn’t come to mind - but the sound of crunching does. Like the children’s book about the hungry caterpillar who just ate through everything in front of it. Crunch, crunch, crunch.

Underneath the Hydrangea - right side detail of diptych © Melinda Hurst Frye

Bio: Melinda Hurst Frye is an exhibiting photographic artist working in themes of implied environments and shared experiences within the still life aesthetic. Her current work illustrates the mystery and activity of subterranean ecosystems. Melinda holds an MFA from the Savannah College of Art and Design and is a dedicated member of the Society for Photographic Education. Melinda Hurst Frye teaches photography at the Art Institute of Seattle, holds occasional workshops and is an artist member of CORE gallery in Seattle, Washington

Interview by Jon Feinstein