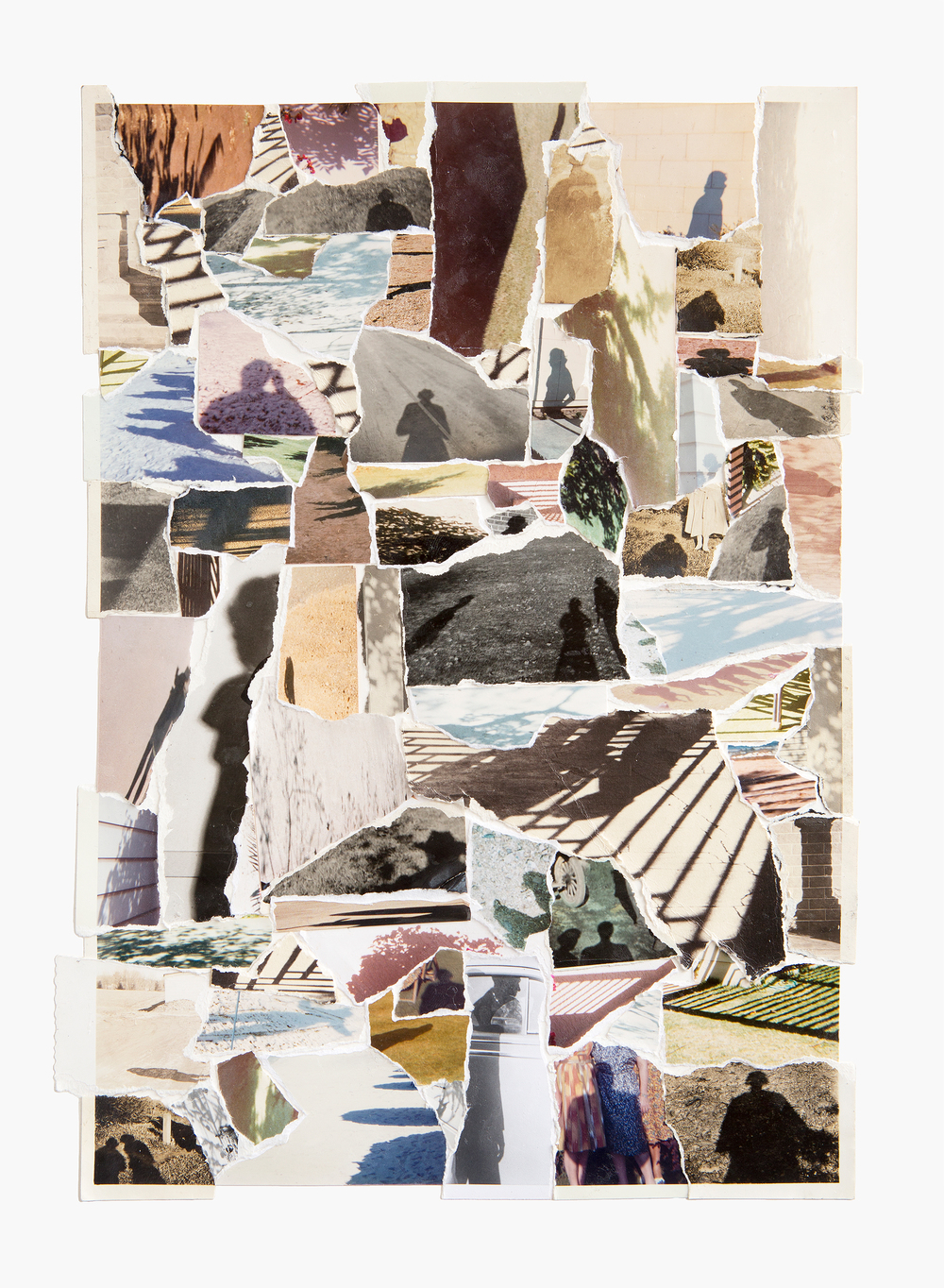

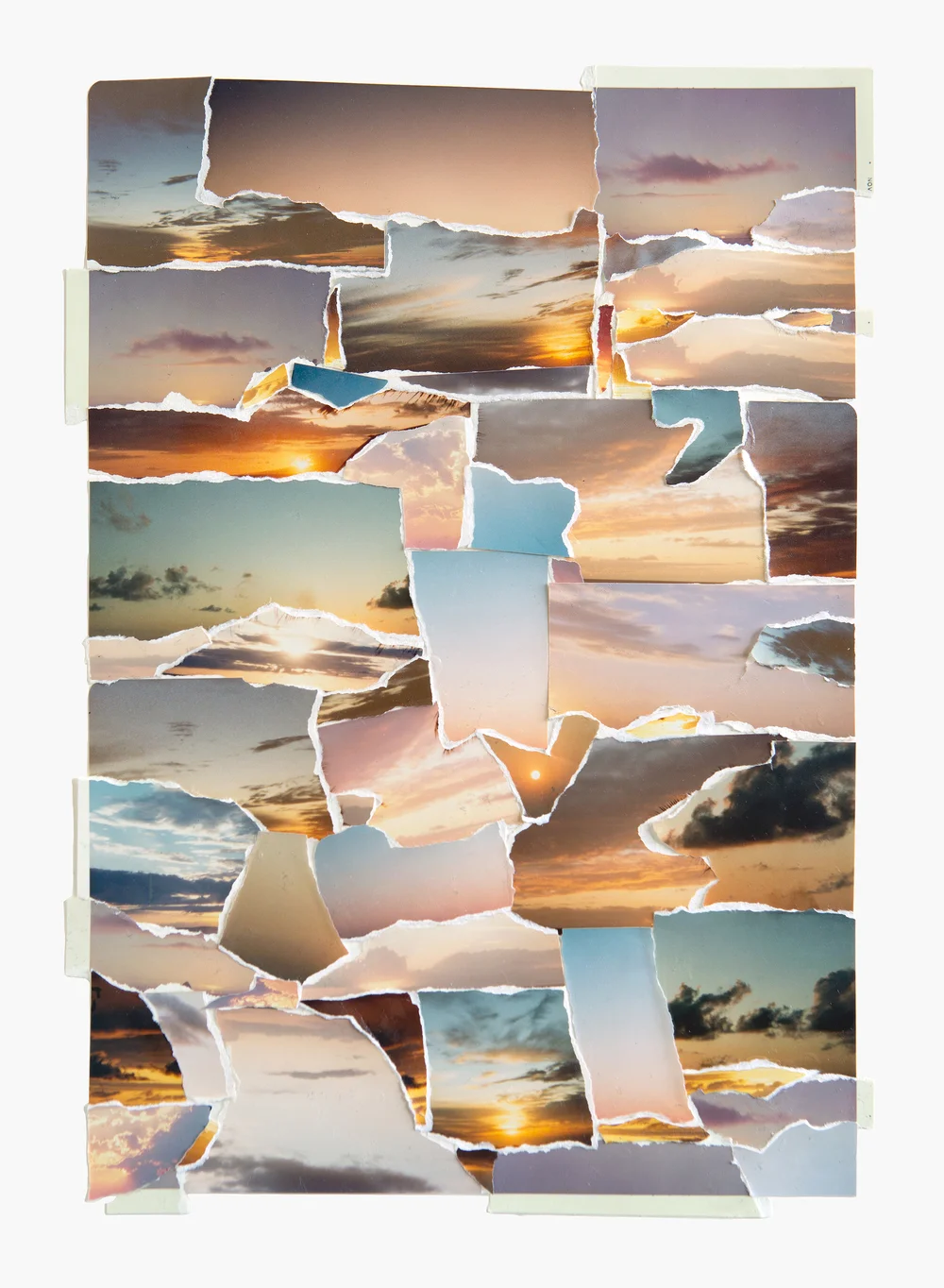

Shadows, 2016. © Joe Rudko

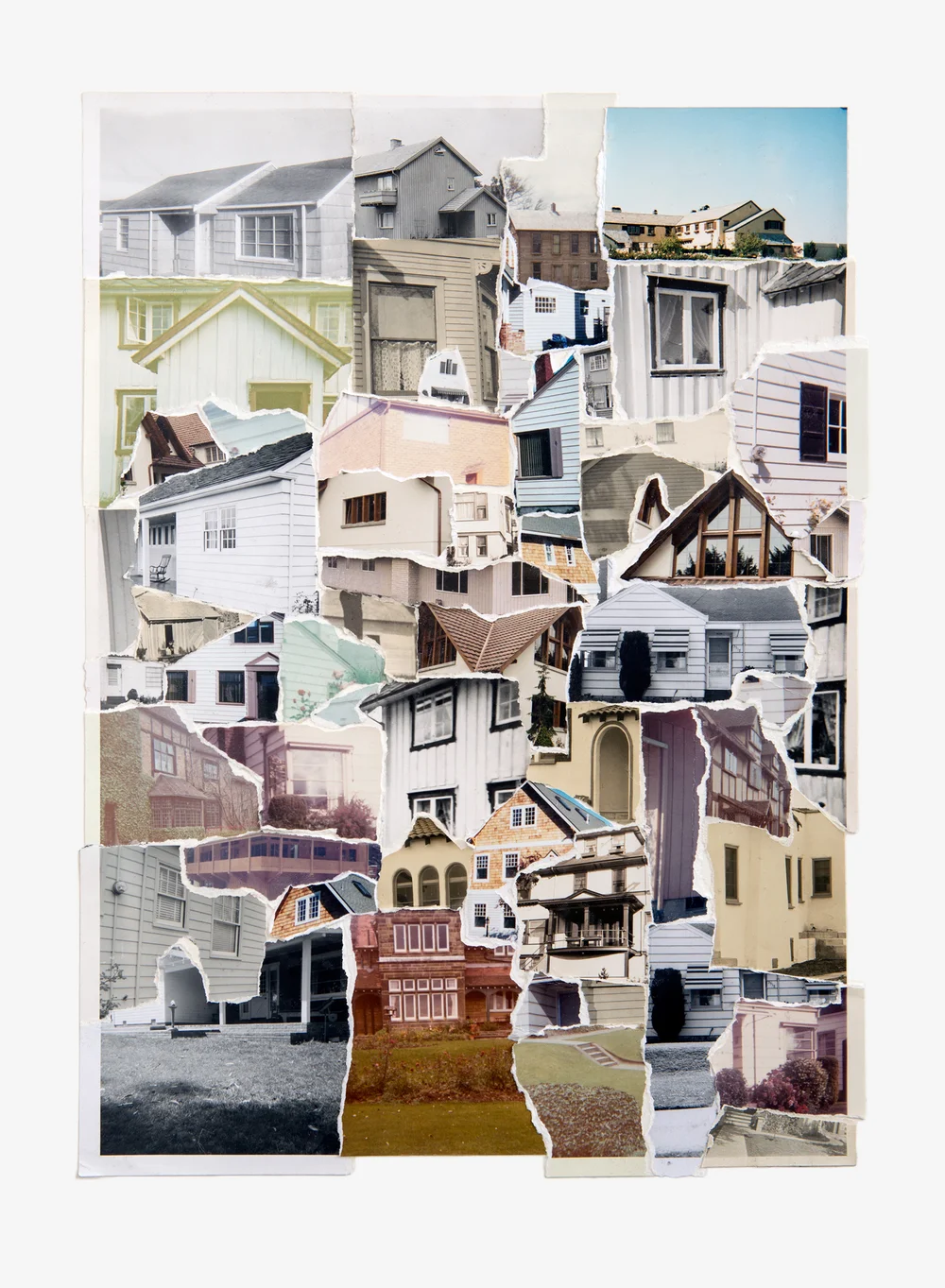

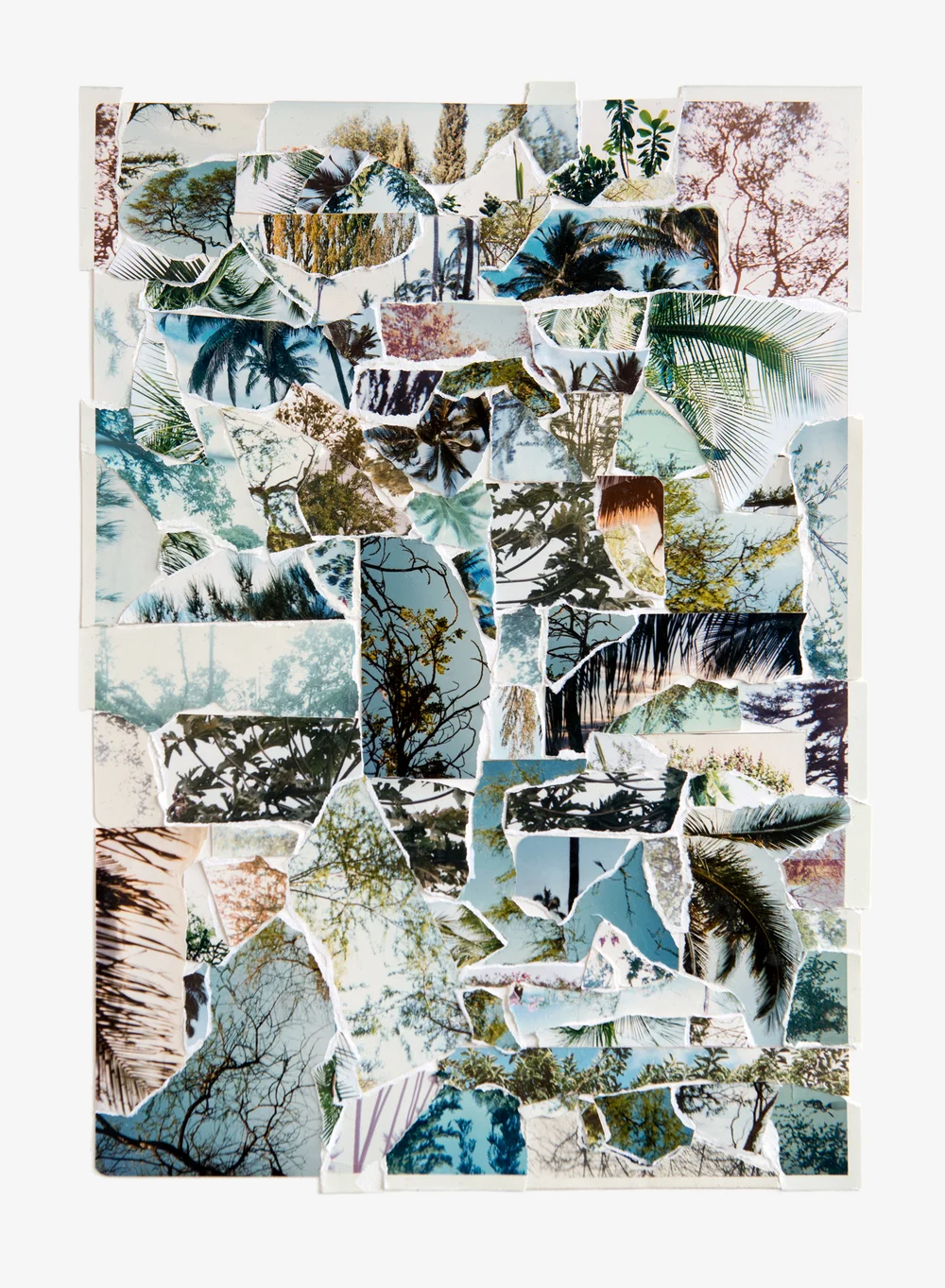

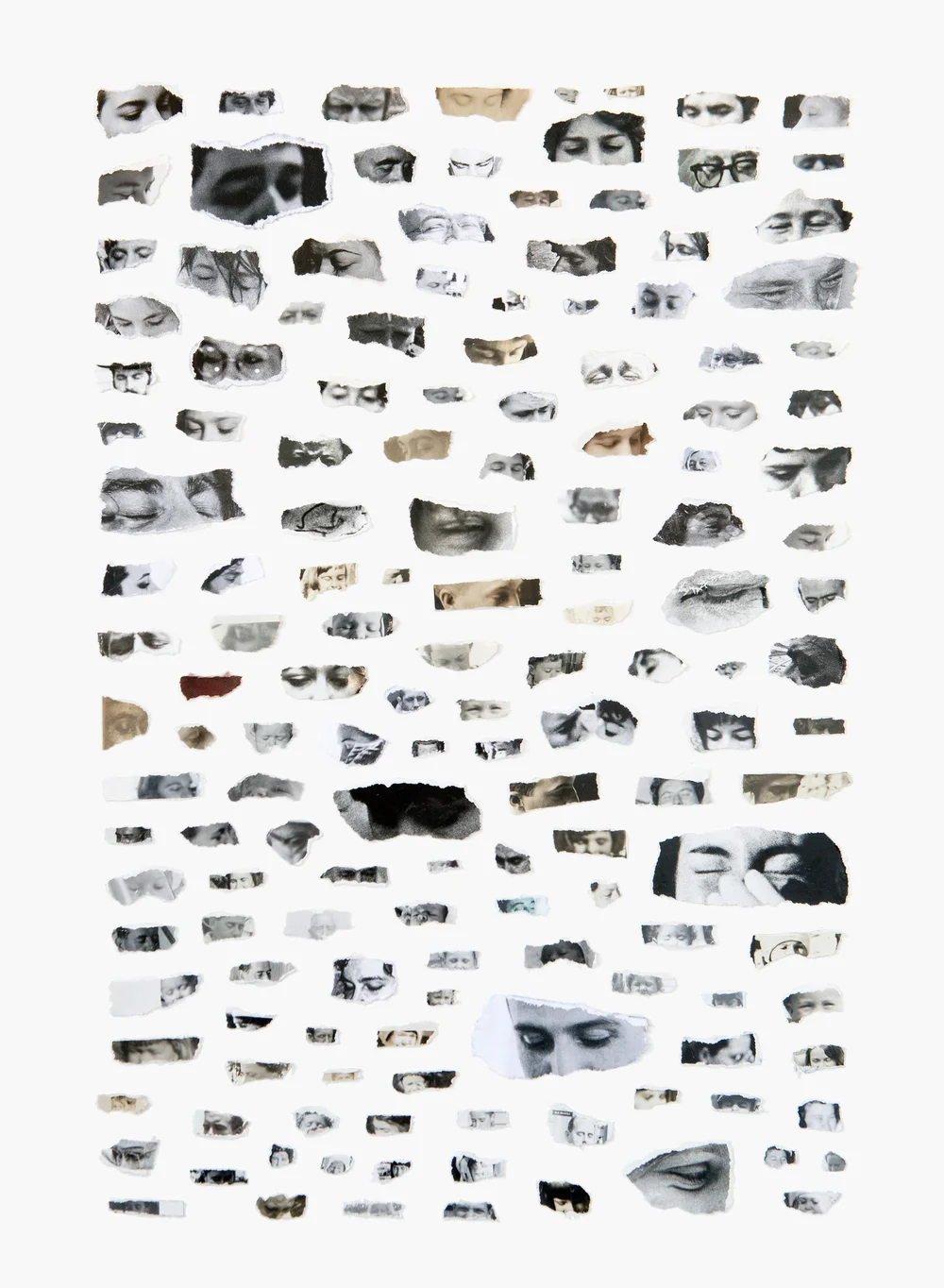

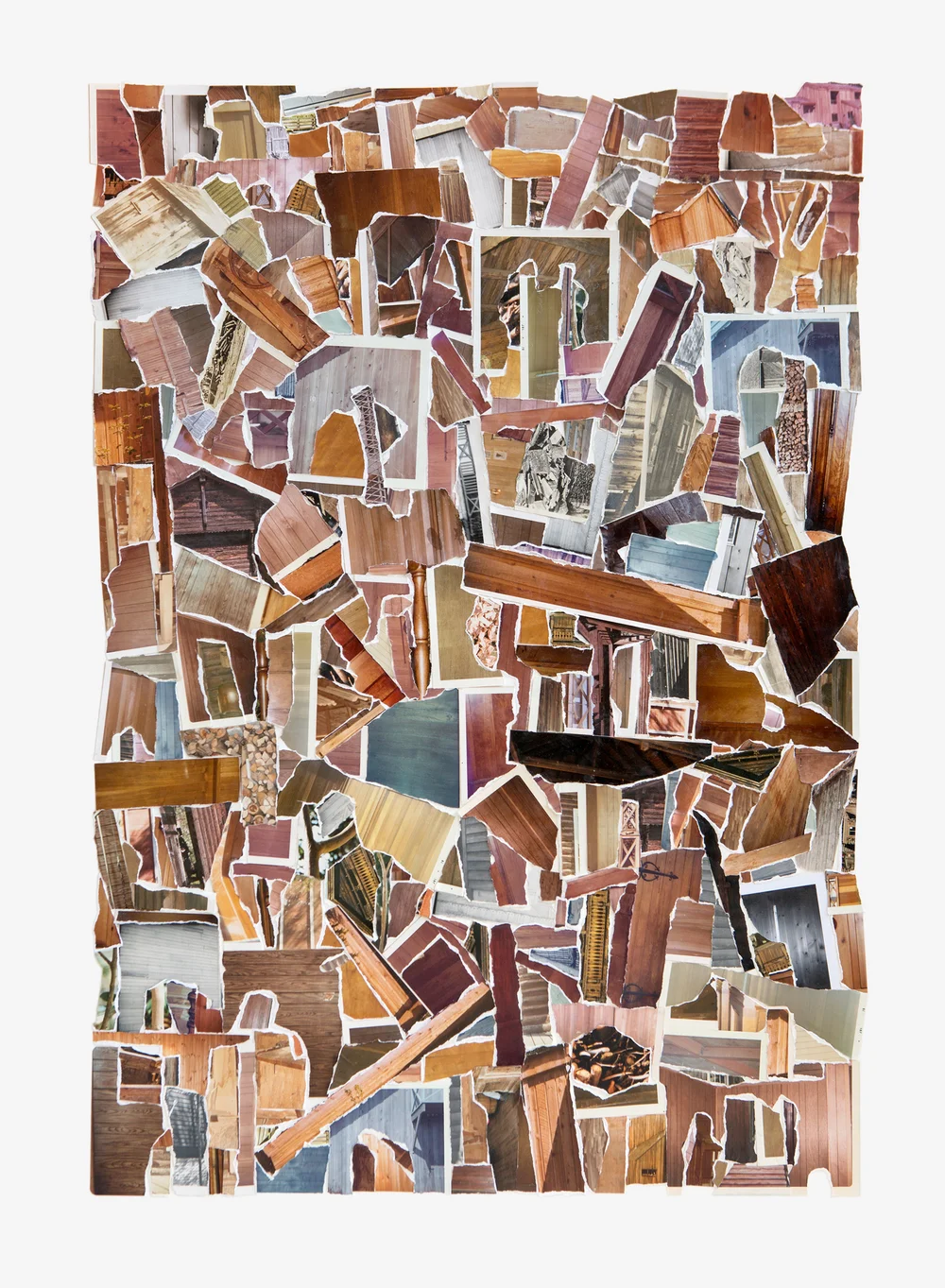

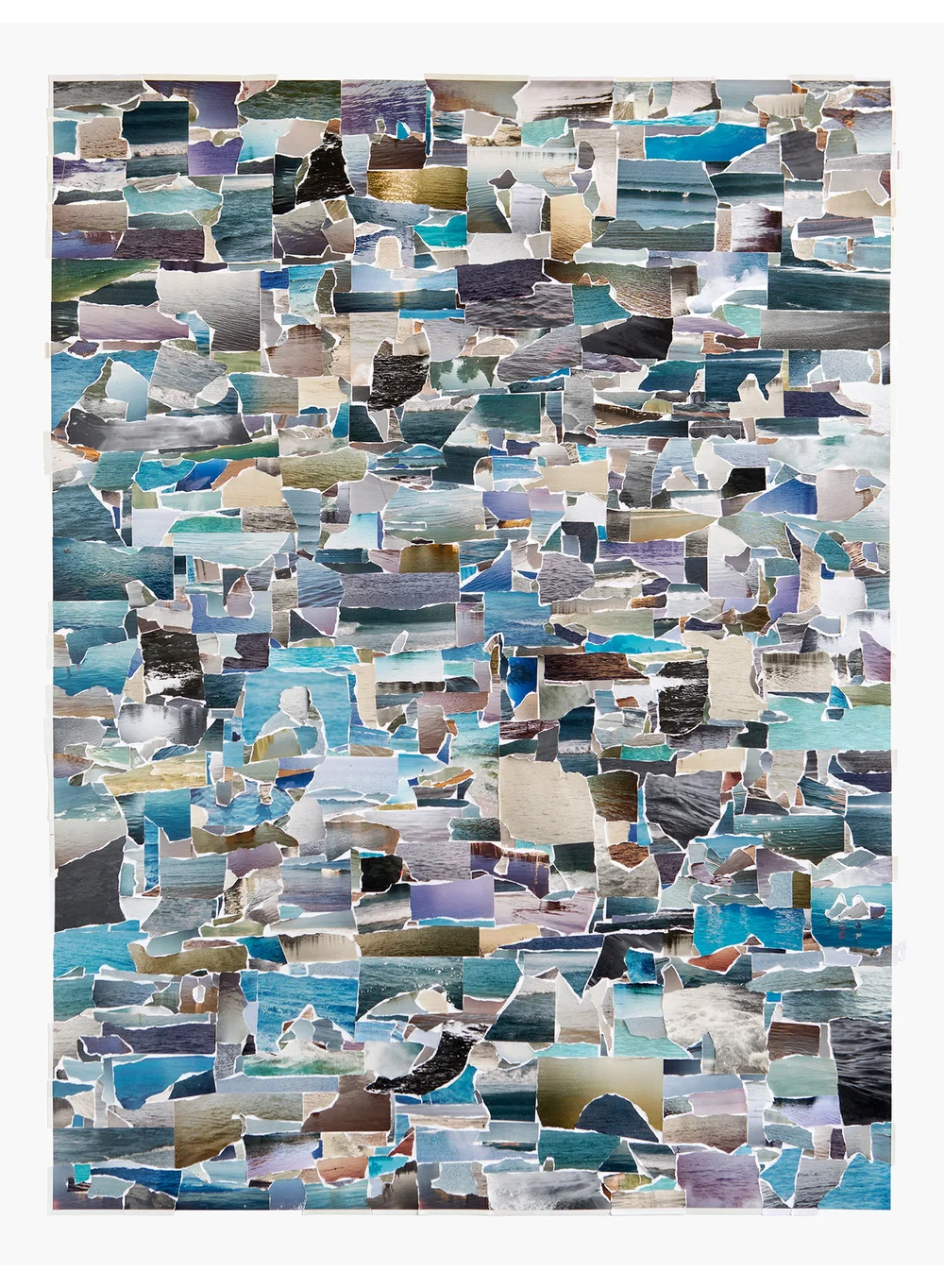

Joe Rudko is quickly becoming one of the most pivotal figures within the Pacific Northwest emerging art and photography community. His collages of found vernacular photographs, sourced from thrift stores, antique shops, snapshot collectors and, most recently, from a family archive discovered in abandoned shed in Washington State, turn anonymous, expired histories into sculptural monuments. Building on traditions ranging from the Dadaists of the early 20th century to the 1970's and early 1980's Pictures Generation, and even the recent work of Penelope Umbrico, Rudko's work makes appropriation exciting again. Like Umbrico, Rudko goes beyond simply re-contextualizing of found imagery. He tears up recurring tropes in family snapshots - clouds, water, sunsets and shadows - and reframes them to unveil a collective experience of viewing and valuing the world. We spoke with Rudko on the occasion of his solo exhibition, Album, on view through July 2nd at PDX Contemporary in Portland, Oregon.

Housing Development, 2016. © Joe Rudko

Jon Feinstein: How long have you been working with found photographs?

Joe Rudko: I think the first time I used them in a composition was probably 2010. But I started collecting them when I was a teenager.

How did you get into collecting them as a teen?

I found a small pile of photographs in an antique store. I think what initially hooked me was that a few of the people in the images looked like they could of been relatives of mine. I think a lot of personal snapshots look like they could belong to anyone because of the limited printing processes and trends in photography at the time, so they end up being relatable at least on that level. There's something magical about feeling a personal relationship with a photograph when rationally you know you have no physical connection to it.

You're two years younger than Photoshop -- as "digitally native" as it gets: yet your process is entirely analog. Does it matter?

I think that it does matter. I grew up between the two worlds, and that’s where there's tension in my studio. I’m often taking pictures of a work as it progresses, so that I can touch base and see how it works as an image. Even though my process is very hands on, I see certain digital language creeping in. There’s an overwhelming amount of fragments in some of the newer works, and that seems very parallel to my experience looking at photographs online.

Cloud Formation, 2016. © Joe Rudko

Blue Sky Through Trees, 2016. © Joe Rudko

The press release for your exhibition at PDX Contemporary refers to your work as a "point of departure." "Departure" from what?

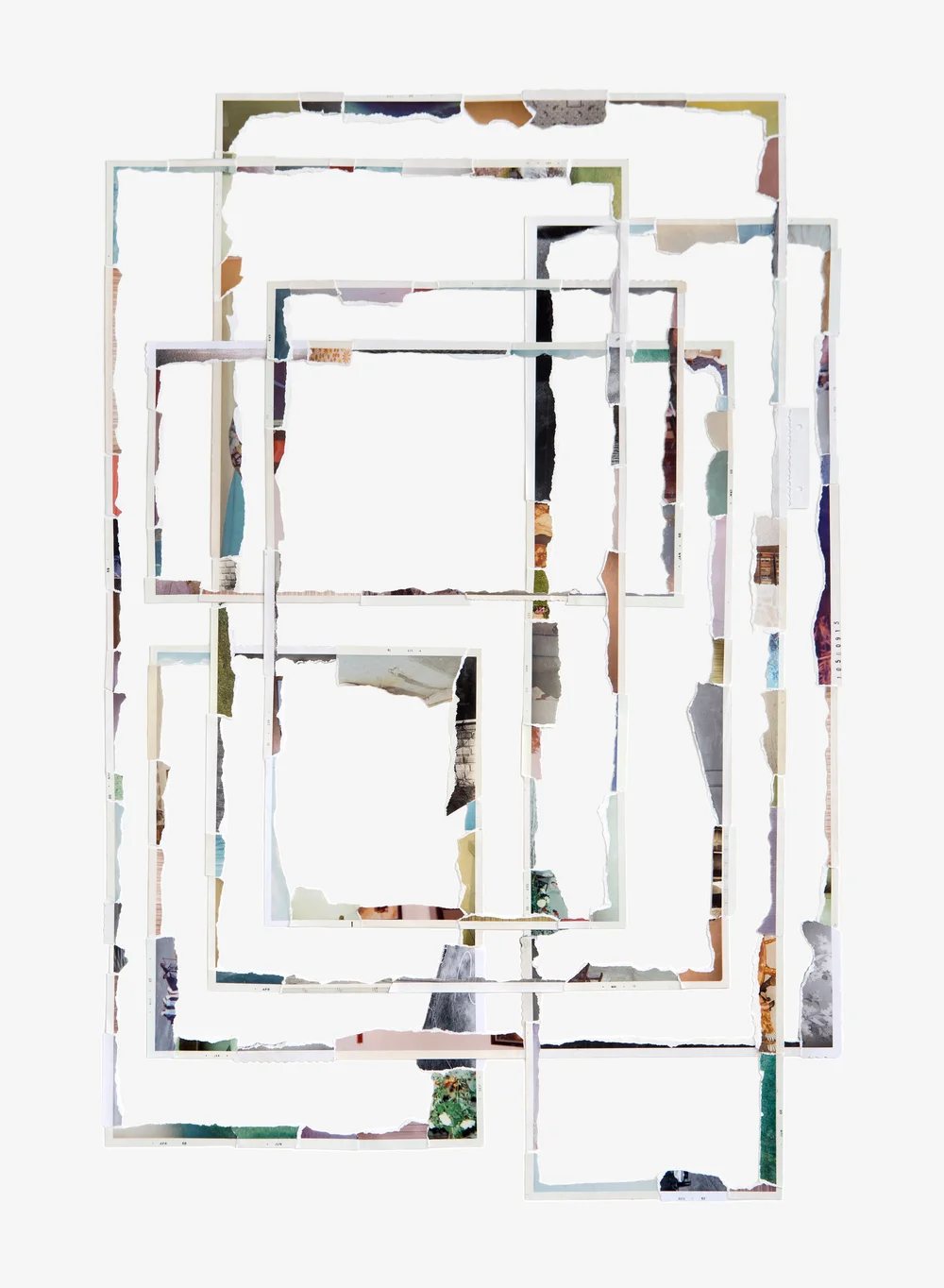

If I'm departing from anything it would be the traditions that make up the medium of fine art photography. There's a certain reverence for the pristine photograph that I'm pushing away from. Rather than wearing white gloves I'm getting in there and tearing the pictures apart to see what happens when you engage the medium in a more physical way.

Your earlier collage work involved drawing lines extending from photographs and other collaged materials, but you've shifted to working in straight collage. What triggered the shift?

The sheer number of photographs I had to work with prompted the shift. It allowed me to engage with them in a very material fashion. Some of the work still feels like a drawing, while some of it feels more like pointillism or cubism. Without the drawn lines, the photographs speak more for themselves, opening them up to a wider array of interpretations.

Eyes Closed, 2016. © Joe Rudko

Building, 2016. © Joe Rudko

Rainbow Lasso, 2016. © Joe Rudko

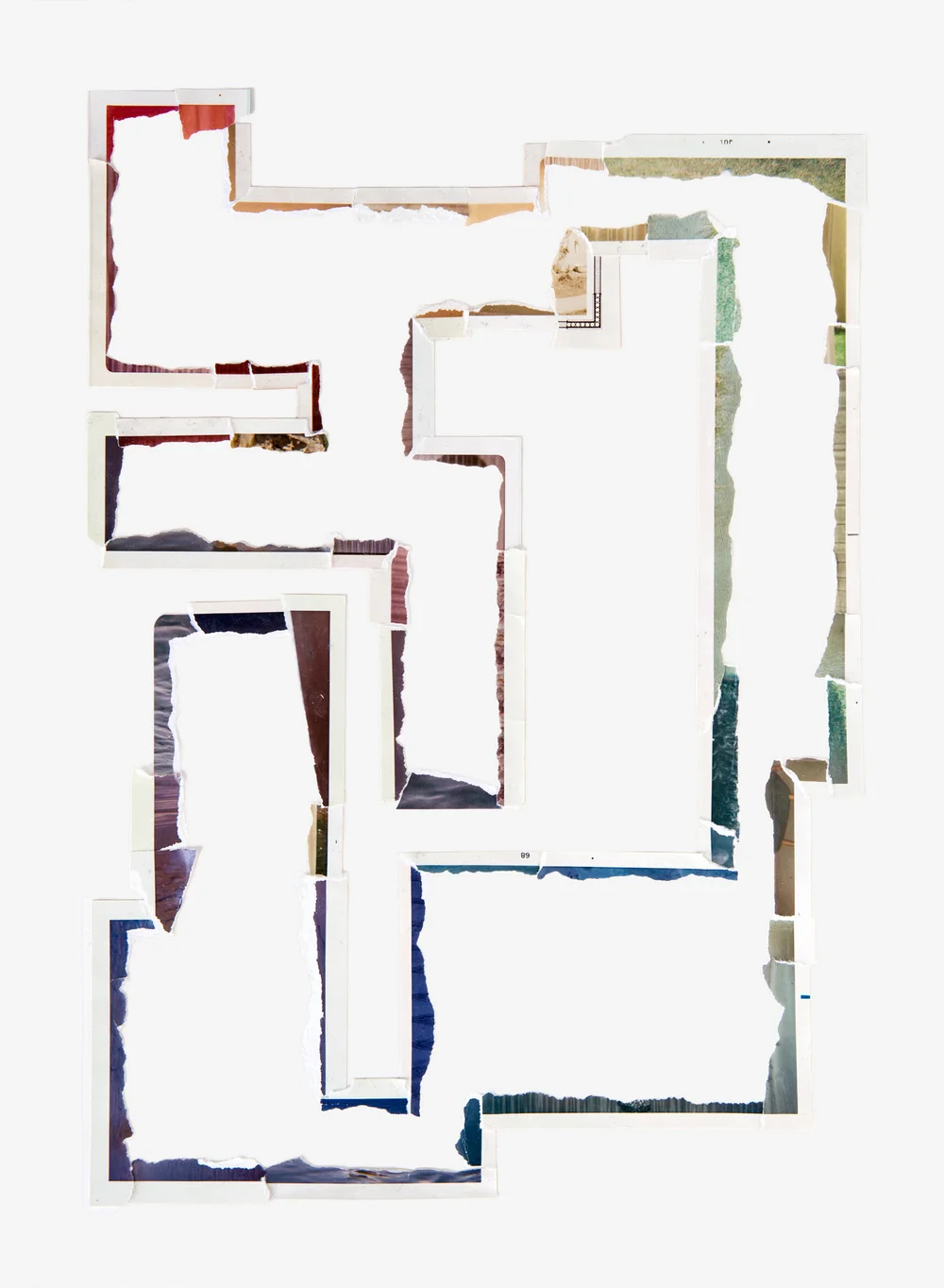

I'm drawn to the recurring absence and removal of subjects and objects in many of your pictures: you're literally ripping the content from the photos and using the lack as new material. What's going on here?

I removed large portions of the photographs as a way to isolate the subjects that appear most often: water, sky, curtains, wood grain, etc. I was using that process as a way to think about the singular perspective of a photograph. By combining all of these single perspectives together, you get a collective viewpoint or an averaging of a particular subject. It's about recognizing how the camera can lie, and trying to bring it closer to the experience of really looking.

Ripping a photograph into a non-rectangular shape draws attention to the fact that something is missing, which is really the case of every photograph ever. There is always something outside of the frame. It's similar to how Basquiat’s crossed out words make you want to read them more. Imagining what isn't in a picture can be a stimulating experience that can add to what is right there in front of your eyes. The blank space allows you to fill it up with your own meaning.

Curtain, 2016. © Joe Rudko

Framing Device, 2016. © Joe Rudko

What inspired you to start creating sculptures like Flower Vase?

The sculpture is coming from a desire to combine photographs with a sculptural form that is derived from the something seen in the pictures. Making a three-dimensional object out of flat images that have illusionary space is almost a backwards photograph. There's also this idea that if you combine the language of sculpture and physicality into a flat photograph it could give a more holistic view of the subject. Cramming mediums together reveals their similarities and differences.

Flower Vase, 2016. © Joe Rudko

The photos for these collages were all found in an abandoned barn, right? How did that happen?

It's actually more of a shed then a barn. A friend of mine recently bought a house just north of Seattle, and there was a shed in the backyard that had piles of stuff left in it. There were about 100 or so albums of photographs.

How much do you know about the original family?

Many seemed to be from the previous family that lived in the house, but it was hard to tell where they were all from. It was strange to find all these photographs that seemed to be bursting with information, but unknowable at the same time.

Your material is in the past, but I'd hardly call it nostalgic. Do you agree?

Yes, It’s all from the past. But it’s someone else’s past, not my own. I think there’s a tension between preserving these artifacts and destroying them in a lot of the work. On one hand I’ve rescued a lot of the images from obscurity, but I tore them up in order to do so.

White Walls, 2016. © Joe Rudko

Body of Water, 2016. © Joe Rudko

Sunset, 2016. © Joe Rudko

Bio

Joe Rudko has rapidly become one of the emerging artists to watch in the Northwest, exhibiting at a remarkable pace and to consistent, frequent praise. He has been in nearly thirty group shows and nine solo shows in Portland, Seattle and New York, prominently featured in the Seattle Art Fair and PULSE Miami Beach, selected as one of eleven artists and innovators on City Arts’ 2016 Future List, created the cover art for Death Cab for Cutie’s latest album, and been published in print, online and in journals. His work is in the collection of the Portland Art Museum as well as in private collections throughout the United States. Rudko graduated from Western Washington University in 2013 with a BFA. He recently completed a residency at the prestigious Vermont Studio Center.

Author: Jon Feinstein