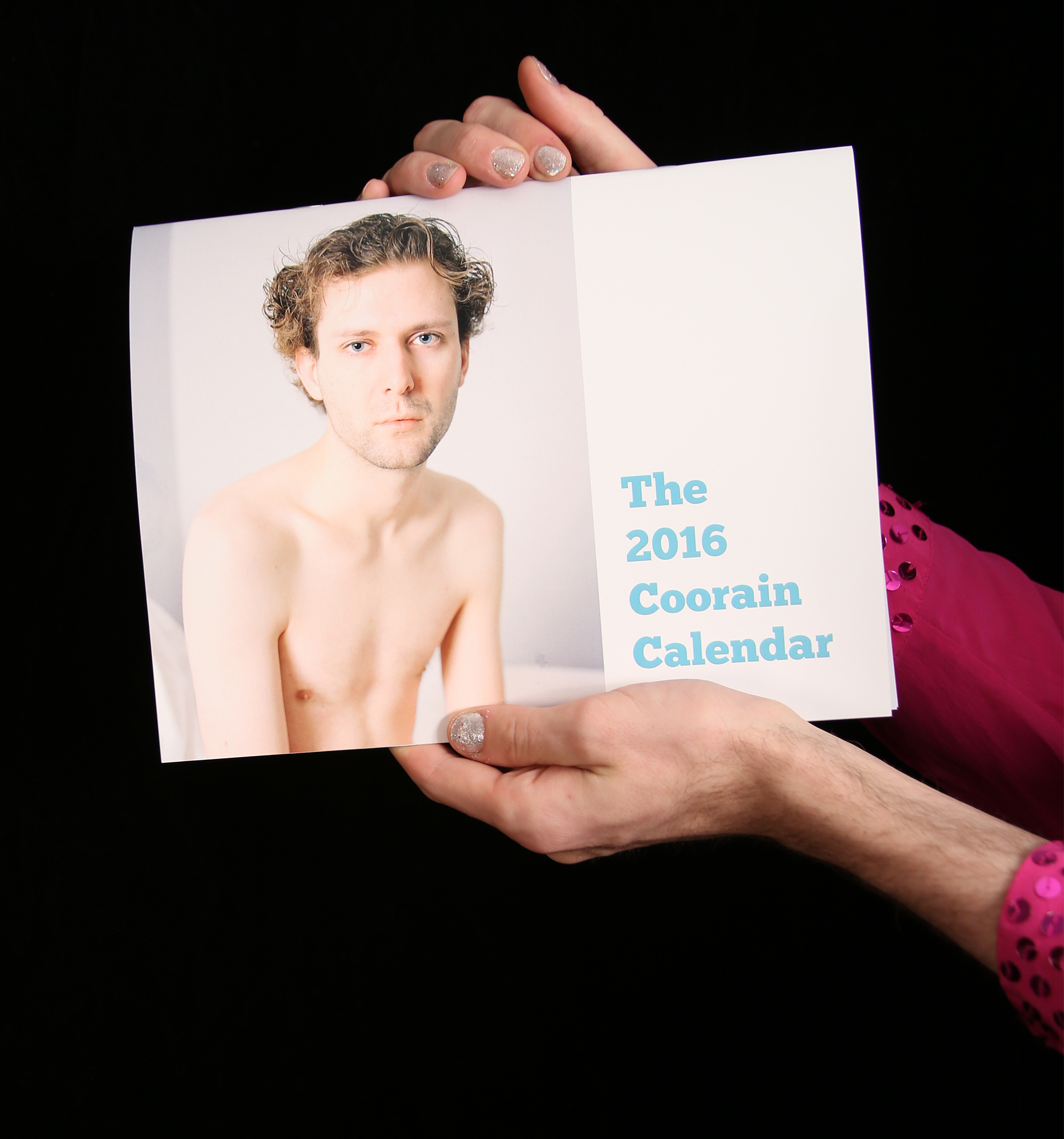

Coorain by Brian Christopher Glaser

Coorain Devin, host of the new video-art talk-show web-series, Coloring Coorain, is a renaissance-hatted conceptual artist, TV star and cultural wonder producer who uses campy humor to address complex themes ranging from feminism and queer identity, to poetry, vernacular photography, and even personal health issues. Their playful, and often heartwarming approach, which credits influences spanning Candy Darling, Oscar Wilde, Dave Eggers, and John Waters, help to make these issues more accessible to a range of audiences without dilution or sacrifice of content. Corain recently collaborated with 15 photographers to produce a calendar picturing the artist as a means to to explore some of these same issues "at a time when queerness is frequently appropriated, repackaged and deployed as entertainment." Coorain's work gives agency and visibility to them, and their influence on contemporary pop culture. We interviewed Coorain to learn more.

Coorain by Joyce Taihei

Jon Feinstein: Tell me a bit about your background.

Coorain: I grew up in rural Maine, where I was raised by an artist and scientist. From an early age, there was a push to explore and create. Given that there were few people around, I became a voracious reader and I really ended up creating my own worlds to play in.

As I grew up, I went to school and focused on philosophy, printmaking, and film. I was, and still am, enamored by the concept of multiples. With a group of other students, I founded Salad, a magazine and art object. Each issue of the publication was different, from one entirely screenprinted issue, to the last issue, a box of CD’s, zines, and pamphlets. Our collaborative process was very successful, and has stayed with me as I've developed.

After school, I became involved in community television. The radical beginnings of community cable have pushed me towards a collaborative, community based practice. I still think about multiples, with projects like this calendar or my upcoming perfume, and in a way video is a multiple.

Coorain by Caleb Cole

What inspired the creation of the calendar?

As my practice is in part an investigation of celebrity, I’ve become interested in the labor surrounding the production of modern-day celebrity. While lip service is paid to the idea that celebrities like Rihanna or Justin Beiber are creative, cultural producers, it is very clear that their public image is managed by a board of directors and teams of social media managers.

This calendar was a chance for me to curate a team of cultural producers and have them create and manage my public image.

How does the calendar fit into your larger practice?

The calendar continues my collaborative/organizational approach to making work. For me, this is the first time my practice has begun to question authorship, since in a large part, I did not create the imagery in this project. I did work with each artist and we discussed what we wanted to make, but I wanted the artists to have the final say.

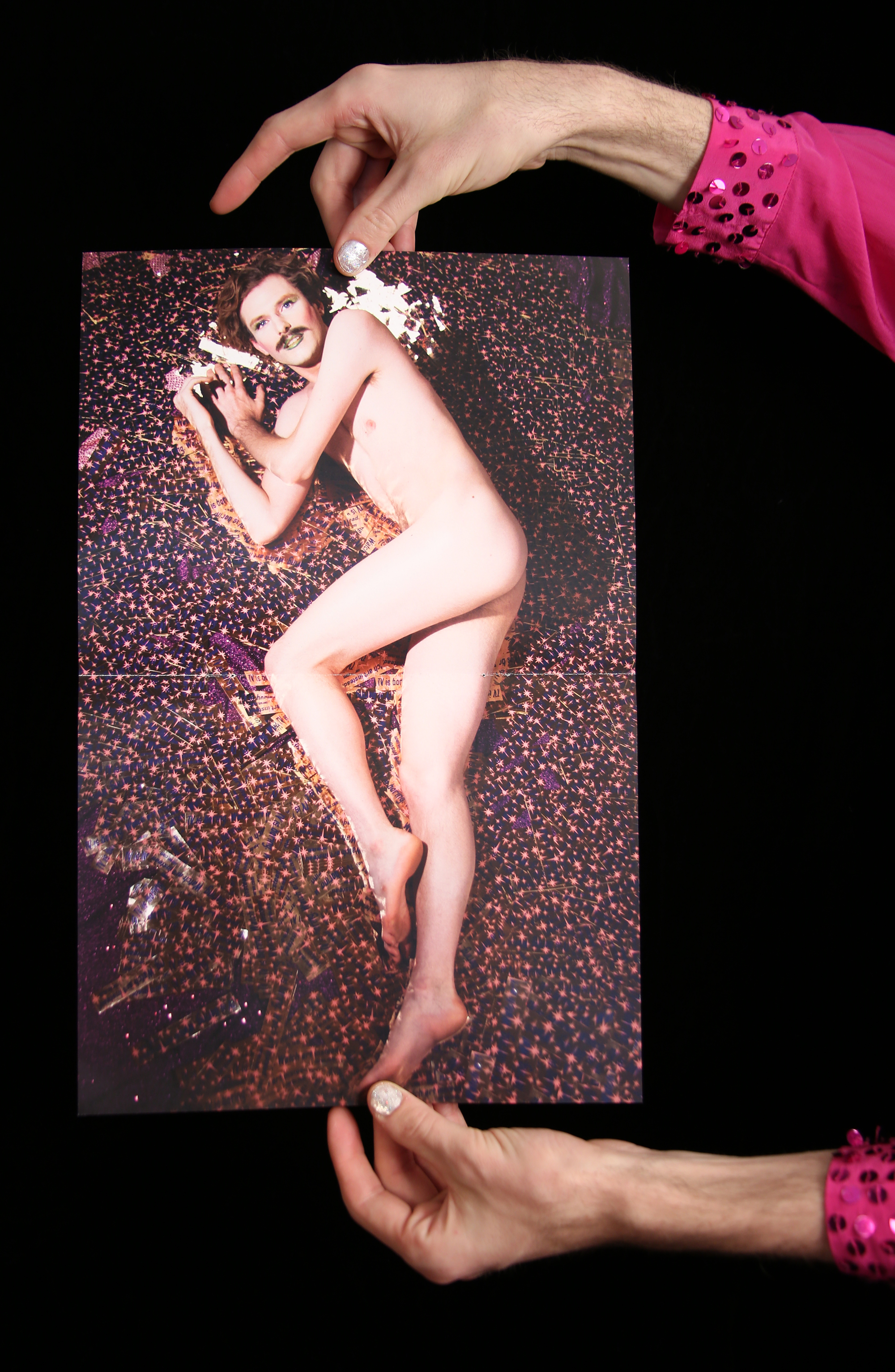

How did you select the artists to collaborate with?

I chose artists whose vision I believed in and whose practice I found intriguing for whatever reason. I was really excited to work with Xtina Wang, a friend, but I was also so excited to meet some of these artists, like Amiko Li, whose work I really admire, but otherwise might never have a chance to talk with or meet.

For me, this project is a little political; it’s not often that queer folks are in charge of their media representations. To that end, I primarily chose queer artists, which is something I’m delighted to say will continue in the 2017 edition, which I’ve just started to work on.

Coorain by Xtina Wang

"Coorain" is also a cultural figure/ pop-icon?

From 2010-2013, I worked on a body of work about celebrity. I wrote critical essays and made a series of prints about my desire of and revulsion to fame. After a while, it started to become boring, repetitive, and too similar a myriad of other artists. I needed a new take for my work and started to make work based on the idea of myself as a celebrity. This “permission” lead me to use myself as a figure to enact the kinds of change and community organizing I wanted to see, for example reporting on exciting emerging artists. I have often used my self-created celebrity status as a way to create the conversations about contemporary art and society that I feel are missing from public discourse.

In your own writing about your work, you mention a particular affinity towards ‘psychedelic drag queens, obscure poetry, “pop culture detritus”, vernacular photography….’

I find myself drawn to psychedelic drag queens, like the Cockettes, because they have a lineage of radical, utopian experiments. There is so much that attracts me in these figures and communities- wild visual stimulation, the idea of gender falling away, as well as a sense of inner peace from meditation and focused consciousness. They acted as activists, but not by protesting per se, but by living out the ideals they professed.

Taking pop culture seriously has always been part of my practice as an artist. I grew up with parents who don’t hold a high opinion of pop culture, beyond a select few figures they deemed worthy of any attention. But when I look around at the world, it’s clear to me that pop culture has a real, lasting impact on cultural patterns. I’ve found that I collect bits and pieces that reflect my own view of the world and of its possibilities and I hope to scrape together something better out of it all. The rest, I could leave behind, but for the time being, thinking about it critically feels important, because it’s a daily reality that real people engage with this material.

Poetry is something I’ve always wanted to be more literate in, but have never really related to. Somehow I’ve stumbled across a few things that have stuck with me. Things that speak in a language I understand and just feel comfortable. Michael O’Brien has this gift that I both understand and don’t- reading his work is like reading Wittgenstein's Tractatus. Is it poetry? Is it philosophy? All I know is it pushes my thinking and really, what more could I ask?

With the advent and near-universal dissemination of the camera phone, vernacular photography has become the dominant form of expression in American culture. I don’t know where this is going to take us, but vernacular photography, both in its digital, contemporary form, and older, analog form feels so important and relevant to current practices in art. At a basic level, artists need to be aware of their audience and in the past decade, we’ve seen a huge shift in how audiences interact with photography.

Coorain by Amiko Li

How is Fluxus particularly influential to your work?

Fluxus has given me permission to create the work I make. Little of my artwork fits in a traditional gallery setting—my most successful project is a television show, that airs on community-access television and through the internet. Fluxus created the space I’m now occupying as an artist. Dada did begin to look into these ideas, but it was really Fluxus that questioned reified art objects and sought to place art in mundane, everyday situations, like on a television in a living room or a calendar hung up in a kitchen or office.

Recently, Fluxus has influenced me as I’ve more consciously honed on a collaborative art practice. Fluxus works are often based in some kind of participation. Yoko Ono’s Cut Piece is a clear example of this, but the reliance on scores, scripts, and systems pushed many Fluxus artists away from a traditional sense of authorship towards something that looks more like a group project.

You use camp and humor to address serious topics ranging from gender dynamics and feminism to mental health, anxiety etc. Why is this particularly important to you?

Honestly, I’ve never felt comfortable discussing a lot of this stuff outright, so camp and humor are a way to deflect the tension, but still bring up important topics. I think it’s not just more comfortable for me, but for viewers too. It’s a way to make people relax and sneak in a social justice agenda without feeling confrontational.

Besides my own comfort, using camp to promote equality in its various forms makes my work feel worthwhile and more than just beautiful masturbation.

In one of your videos, you ask an interviewee 'If art wasn't an option, what would you do?'

How would you answer this question yourself?

This question is harder than I thought! I’m tempted to say a reference librarian, because I’ve worked in libraries for so long (going on 8 years now) and it really puts you in touch with so much information. I’m frequently jealous of my colleagues in the reference department who look up answers to complicated questions for a living. I really love reading nonfiction and learning facts about the world and being a librarian makes you do that all the time. If art doesn’t work out, librarianship could be for me.

My other answer, which feels like a cop-out, it architecture. It feels like cheating because it’s really a form of art, but at the same time, it is a world away from what we consider the “fine art world.” I’m really interested in how a built environment can affect identity formation. I didn’t realize it, but I’d never really been in a proper suburb until 2015 and it rocked my world. I grew up in rural Maine, where the built environment hasn’t really changed much since the 1930’s. If I could, really, I’d just be Denise Scott Brown.

Coorain by Zoe Perry Wood

How close is Coorain the “pop-culture figure/ talk show host” to your own identity, and how much is a stage creation?

We’re pretty similar, although, like everything on TV, my personality gets exaggerated. The differences come in when I use the project to let myself be who I really want to be. I’ve always wanted to be popular, but have been too shy, too book-smart, and too weird. In many ways, this is a reflection of “self help” culture in America, where I’ve created an aspirational alter-ego. I think this is the same reason Marilyn Monroe has had such a lasting impact on the American psyche- Norma Jean didn’t like herself, so she created someone better. It’s the same with Divine, Rihanna, and even Jeff Koons.

Part of my overarching goals as an artist is a knowing collapse of art and life, and in practice this means collapsing reality and its mediated copies by inhabiting this pose of the becoming celebrity. I’m fascinated by this film of glamor we coat on crap to make it celebrity culture. What is it that makes it so fascinating? We know that it could be anything or anyone under the film, but whatever it is, it makes everything underneath worth obsessing over.

Coorain by Nabeela Vega (Jan)