In 2013 when Humble relaunched after a temporary hiatus, I invited Blake Andrews to participate in one of our first online shows on the new platform: “Tough Turf: New Directions in Street Photography.” I was drawn to Blake’s ability to both fit within the traditional definitions of the genre (decisive moment, no manipulation, etc) yet break the tropes that have continued to hold much of the genre back. He was (and still is) just a dude capturing the ragged magic of life as it happened. In photo after photo, chance aligns to create strange fictions in every day life. The way a baby’s head cradled in its fathers arms, photographed near a toddler walking by can create and amalgamation of a species. Or how someone’s legs on a body dressed in all black walking down a street, when hit with the right beam of sun, can look like just a pair of legs walking down the street with no body at all. It’s weird, funny and strange with the right amount of snark to keep me looking.

After missing each other multiple times in real life, I got in touch with Blake over email to learn more about what drives him to make pictures.

Jon Feinstein in conversation with Blake Andrews

Jon Feinstein: There's a direct spontaneity to all of your pictures – I'm not talking some recycled philosophy on a decisive moment or anything like that, just a sense of grabbing some soul from what's immediately in front of you. Sometimes it’s abstracted by happenstance, sometimes as direct as a middle finger at the camera. Do you think about it that way?

Blake Andrews: It might sound corny but I've always tried to live in the moment. “Be Here Now,” to quote the old Ram Dass mantra. That was a book I discovered on my parents' shelf in high school, and it made a lasting impact. My wife and I make a good pair because she's always planning things several months out, while I try to restrict my attention to now. We balance each other.

Be Here Now fits well with photography, a medium which has a very tangled and deep relationship with the present (not to mention the past and the future). As you say, a lot of my photos are caught on the fly. They would not exist in the same way a second earlier or later. There's a degree of chance/uncertainty which is endemic in that process, and fundamental to it, not just to photography but to my general worldview. It's probably why I've been lumped in with street photography and HCB, even though all those labels are irrelevant to me.

Your recent Vice article on new street photography offered counter-examples to that worldview. Most of the photographers you showed were unleashed from the present. Instead they pre-conceptualize projects, then shoot or recreate the images needed, followed by post-processing/editing, etc. So, although they are all set in public "street" environments, they lack the core "now" ingredient. Just my two cents. I'm sure many will disagree.

Feinstein: I actually received some pretty strong words from a few folks, including one pile-up public shaming on FB that I won’t go into now. But my point in that Vice article was not that “anything shot in the street should be considered street photography” and instead that all these photographers who the “hardcore” folks are dismissing, deserve to be considered for the legacy they owe folks like Bresson, etc. Everything evolves. We could probably spend hours on this discussion, but let’s focus on your work. What's driving you?

Andrews: Good question. A psychiatrist might say that I'm fearful of letting go. Maybe I clutch hold of time, in a futile effort to freeze the hourglass? If I can't keep those sand particles from falling, perhaps documenting the midair plunge is the next best thing?

Feinstein: What moves you to make pictures?

Andrews: At this point it's so integral to my life that it's hard to untangle. It's my journal, my crutch, my passion, my experiential medium.

© Blake Andrews

© Blake Andrews

Feinstein: How did you start photographing?

Andrews: I took a basic photo class in my early twenties. Night school. Back then it was all film, so I learned 35 mm and darkroom processes along with a bit of photo theory. From the very beginning I was attracted to monochrome prints. Maybe I'd assimilated some sort of hokum that they were "arty"? Who knows. Whatever the reason it sucked me in. 27 years later my methodology is essentially the same.

Feinstein: What was the first picture you remember feeling good about taking?

I took a photo of my dad in about 1994 that I still like. But that's an exception. Most of what I shot back then doesn't hold up for me anymore. Maybe the same will happen with the photos I'm making now? Maybe I'll hate them in 20 years? Who knows.

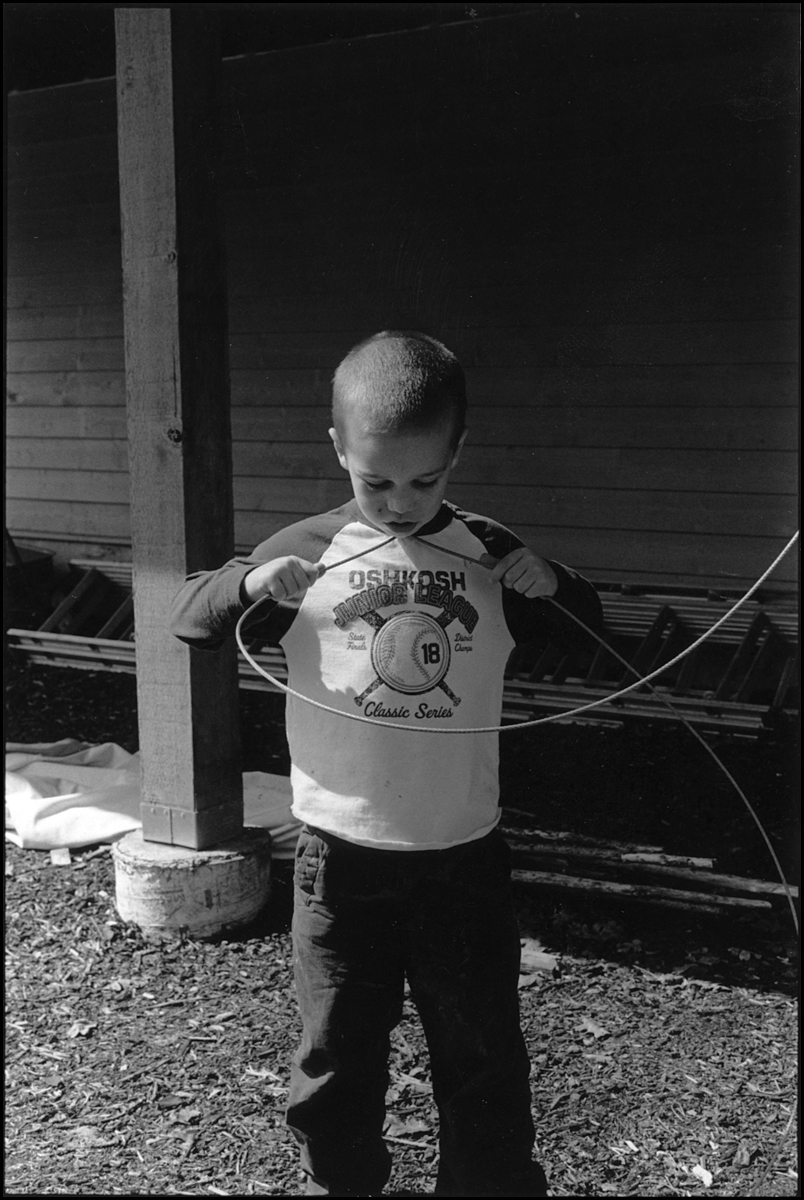

Blake’s dad - sometime around 1994. © Blake Andrews

© Blake Andrews

Feinstein: I read in an interview recently that for much of your photographic life you've only worked in black and white because it helped you "forget the original scene."

Andrews: I believe fundamentally that a scene and a photo of that scene are two separate things. Ideally the photo can have a life of its own without any dependency on the original material. Not easy. But that's the goal, for me at least.

With that in mind, I think it's valuable sometimes to stand back from your photos and view them from the perspective of an outside observer. What would someone think who had no information about the original scene? Since I was at the scene, it's impossible to do this. But forgetting can help. So to aid the forgetting, I generally have a long lag between exposure and editing/printing. For b/w film it's about 18 months. At that point, memory interferes less with my interpretation. But of course it's still there. I can't ever view my photos objectively, and that's part of the fun.

Feinstein: You're now shooting some color – at least a bit – why the change now? What's gotten you more comfortable breaking from the monochrome?

Andrews: It's nothing new. I've been shooting color off-and-on for the past 15 years. I've shot reams of medium format color, digital, iPhone, etc. But monochrome will always be my primary focus, mainly because it is so malleable. It compresses reality into binary form. Information is stripped away. And what's left can become the building blocks of something new. So for myself and the type of photos I enjoy making, it offers more possibilities than color.

© Blake Andrews

© Blake Andrews

The iPhone photograph that created a controversy. © Blake Andrews

Feinstein: Recently a happenstance iPhone glitch put you in a new direction. Tell me about this.

Andrews: A few friends had shown me their experiments with iPhone Panos in social situations, so I thought I'd give it a shot. I first tried with friends. Then I figured it might be fun in street situations. I toyed around with the technique last summer in Boston and New York, and I've used it off and on since then in various crowded situations. I'm still not exactly sure what I think of those photos. There's definitely something to them. The uncertainty and chaos is appealing. But I'm not sure exactly what they're saying, whether it's just an unremarkable glitch in the system or if there's something deeper there. Ask me in 20 years.

The basic situation for most photographers is that it can be hard to escape yourself. After you've made some good photos using a certain methodology, I think it's easy to fall back into doing what you know. And the longer you photograph and the better you get at it, the more tempting that is. So it's a constant struggle to defy that impulse. I suppose that's why I'm often trying to fuck up my photos any way I can. Hand me a new camera and first thing I'll look for a way to shoot it wrong, mis-exposed, upside down, inside a bottle, whatever. Anything to confuse or trick the tool somehow.

For the past twenty years I've always carried at least two cameras everywhere. One is a "good" camera, designed to translate reality faithfully. The other is a "bad" camera which fucks things up. In the past it's been a Holga, Diana, Noblex, Instax, iPhone, Chinon. Lately in the darkroom I've been toying with photograms and chemical glitches. I think that's the kernel of the iPhone Panos, my need to escape what I already know. Back to the psychiatrist's couch?

It's not just photography. With the rise of digital culture, all creative arts hear the siren song of perfection. Convenience is an epidemic! Music, photography, design, writing, etc. I am highly skeptical of perfection. If I ever take a perfect photo, just kill me already.

© Blake Andrews

Feinstein: That new direction led to some tense feelings and an eventual disbanding of inPublic -- the street photo group you belonged to for years.

Andrews: Just to clarify, we have not disbanded. Nick and Nils left In-Public. Nick then reneged on leaving, seized admin control, locked the other members out, and established In-Public as a frozen archive replicating the old content. That's where things stand now. It's a very sad situation. Unfortunately the rest of us were forced to abandon that site and begin fresh with a slightly modified name. We are now UP Photographers, and in the process of developing a new site from scratch.

Feinstein: Did that overall experience change how you think about making photographs?

Andrews: Ha, of course not. It had zero impact on my photography.

Feinstein: Did it make you second guess or reconsider your methods?

Andrews: The whole episode has been educational. I learned that some people can be real dicks. But hey, that's life. In the end you've just got to let it go and move on.

Feinstein: Your writing on photography and interviews with photographers as well as your tone in online photo groups like the Flak Photo Network shares, for lack of a better word, a funny and direct kind of straight up snark - something I've been drawn to since I first came across your work. Do you see a relationship between the two, or is it as simple as "this is Blake?"

Andrews: Yes, I can be snarky. My go-to move is absurdity. It hasn't failed me yet.

© Blake Andrews

Feinstein: I'm very familiar with your writing and photography, and that you at least sometimes take your kids to watch wrestling, but not much more -- what else in your world is inspiring the photos you make?

Andrews: Photographically I'm inspired by pretty much everything and everyone I come into contact with. Finding photographic inspiration has never been an issue. Instead I have the opposite problem, trying to sometimes turn off my photographic brain and limit my production.

If you're asking what else I'm interested in aside from pro wrestling, I enjoy time with family and friends, reading, basketball, kinetic sculpture, DJ-ing, mountaineering, shamanic journeys, local beer, amateur cardiology, writing. That covers most of it.

Feinstein: Most photographers I know hate being asked this question: What do you do to pay the bills?

Andrews: I pay most bills through online banking. With some bills I send an old-fashioned check.

Feinstein: No Venmo? Ok, I won’t push further. Do you have any exhibitions publications, etc coming up that our readers should know about?

Andrews: I just took down a show in Eugene featuring photos of the Eugene Grid Project. I think I'm currently in a postcard show in Spitalfield, UK, but honestly I don't know much about it. This fall I'll be showing at Joan Truckenbrod Gallery in Corvallis, and then at the Linn-Benton CC Gallery in Albany. Most of those shows are local, and probably beyond easy visiting distance of your readers. That's fine. I don't expect anyone to come to any of my shows. They're mostly a benefit to me, to help me organize my work and decide what is worth sharing in print form.

Feinstein: Let’s close this conversation with the “game” you suggested when we first emailed. I come up with a random image idea and you see if you can match it from your archives. Starting with….

A photo of a group of animals:

© Blake Andrews

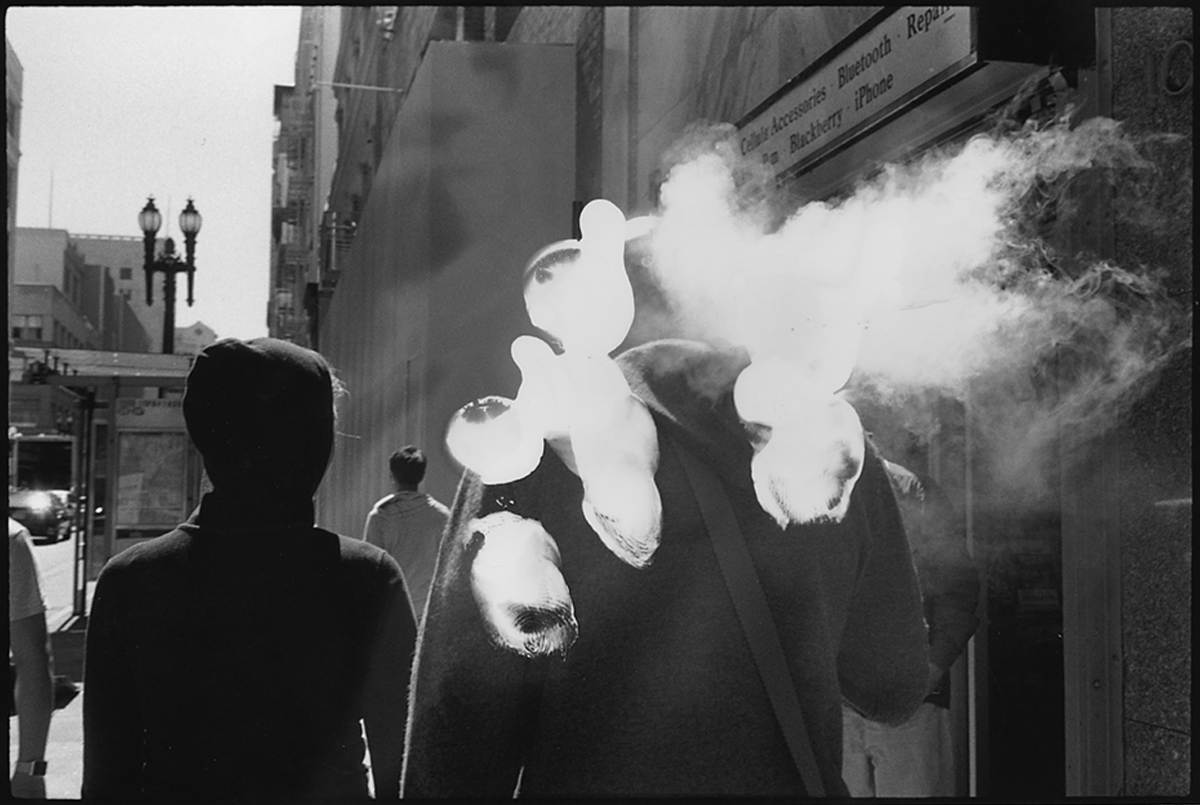

A photo that contains a bunch of street photography clichés, but somehow breaks them:

© Blake Andrews

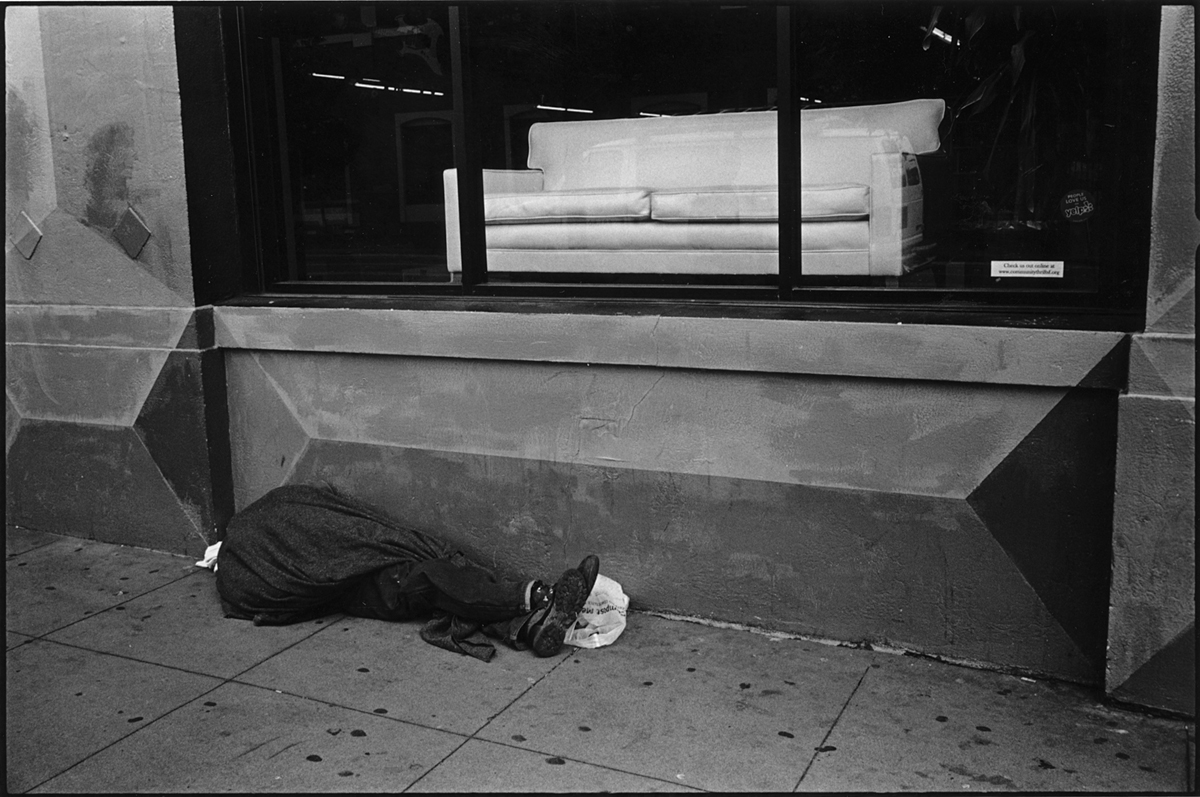

A photo that makes viewers uncomfortable:

© Blake Andrews

A photo that made and/or makes you uncomfortable:

© Blake Andrews

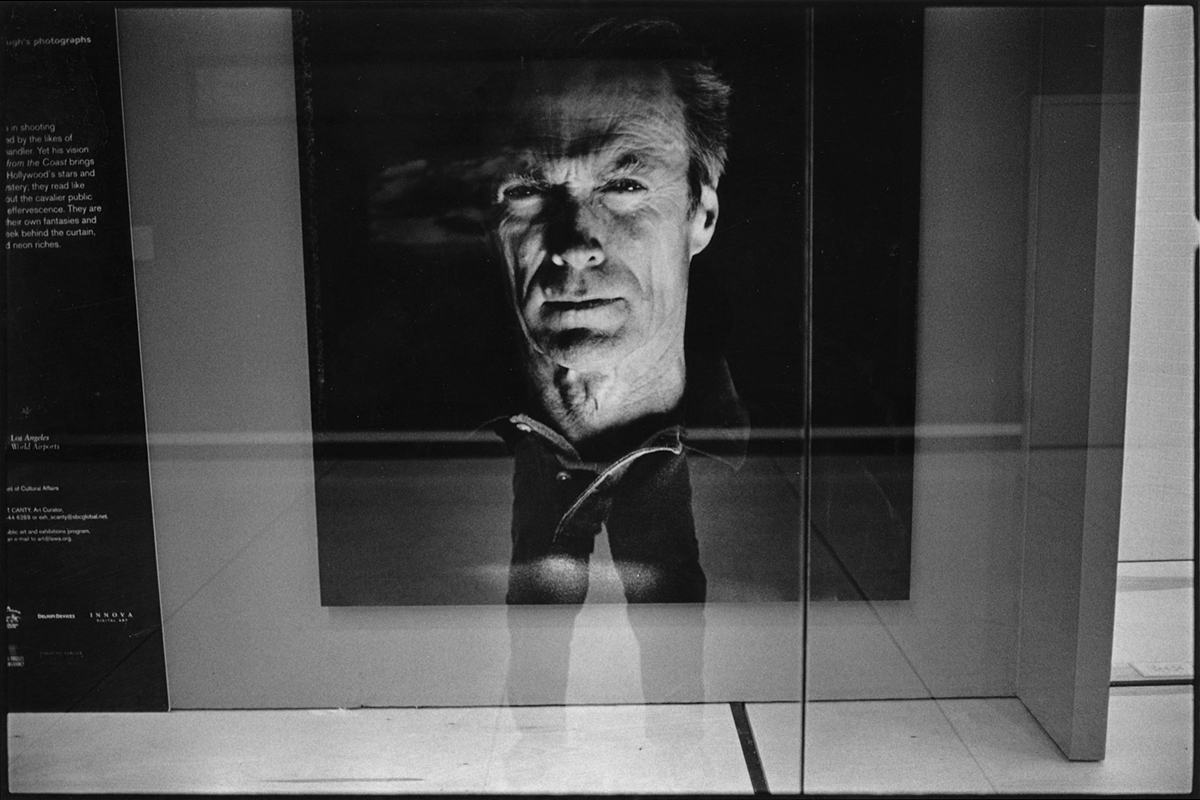

A photo of a celebrity:

© Blake Andrews