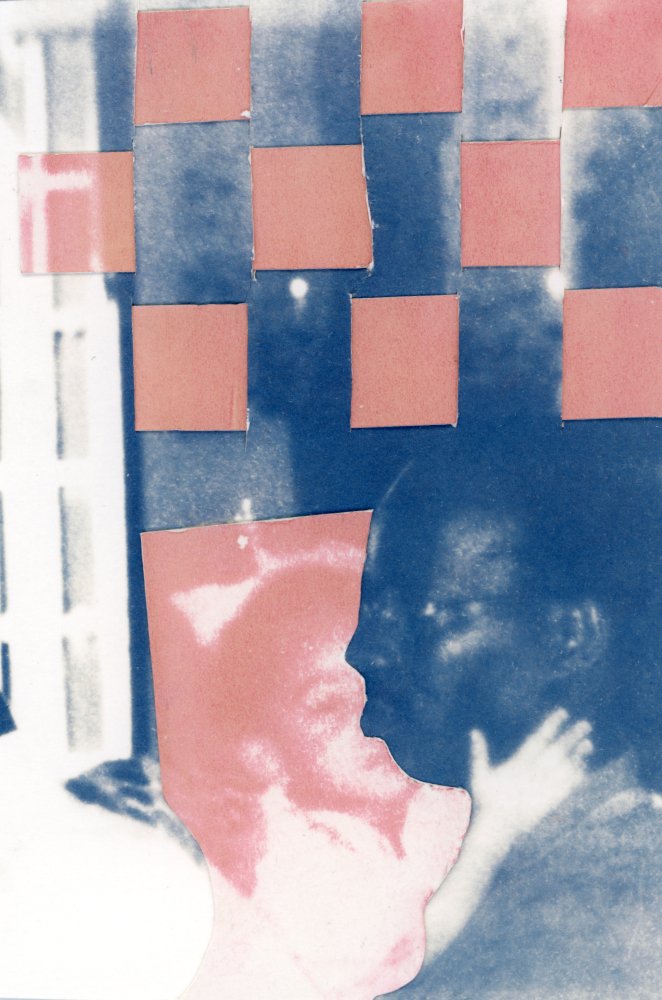

Comfort © De’ De Ajavon

The artist’s new exhibition Synchronicities, Traditions, and Remembrance at The Prelude Pointe Gallery in Marietta, Georgia attempts to materialize the memory of her father’s death.

When De' De’ Ajavon was just six years old, she lost her father. His passing left a gaping, unrecoverable hole that she's only recently been able to process. Using cyanotypes for their rich, murky blues, Ajavon digs through the emotional and physical reminders that continue to haunt her to this day. “Grief is a life-long, ever-evolving experience,” she writes, “and, because I was so young when he passed, I’ve had to spend my whole adult life trying to heal myself.”

Ajavon's images depict literal and metaphorical haziness, serendipity, and a perpetual void – she describes her work as a response to decades of “deep contemplation regarding time’s ability to distort our memories and how we perceive them.” It's a means to support her perpetual grieving process, act as tangible evidence of loss, and, she writes, “as a subconscious lead to the things we might have already known deep down inside.”

The exhibition is currently on view in Marietta, Georgia at The Prelude Pointe Gallery space through March 2, 2022.

I spoke with Ajavon to wade through it.

Jon Feinstein in conversation with De’ De’ Ajavon

Feinstein: Congratulations on your exhibition! The first thing that strikes me is how you cyanotypes as a metaphor for loss. How did you first get into working with cyanotypes/ alt processes?

De’ De Ajavon: I took an Alternative processes class last spring, and my professor was super encouraging and wanted us to experiment with a lot of different techniques. Cyanotypes and the Gum Bichromate processes just resonated with me. To me, these techniques are such beautiful combinations of photography and traditional printmaking. I feel like I’m able to translate something so impalpable like memories, into something tangible and real.

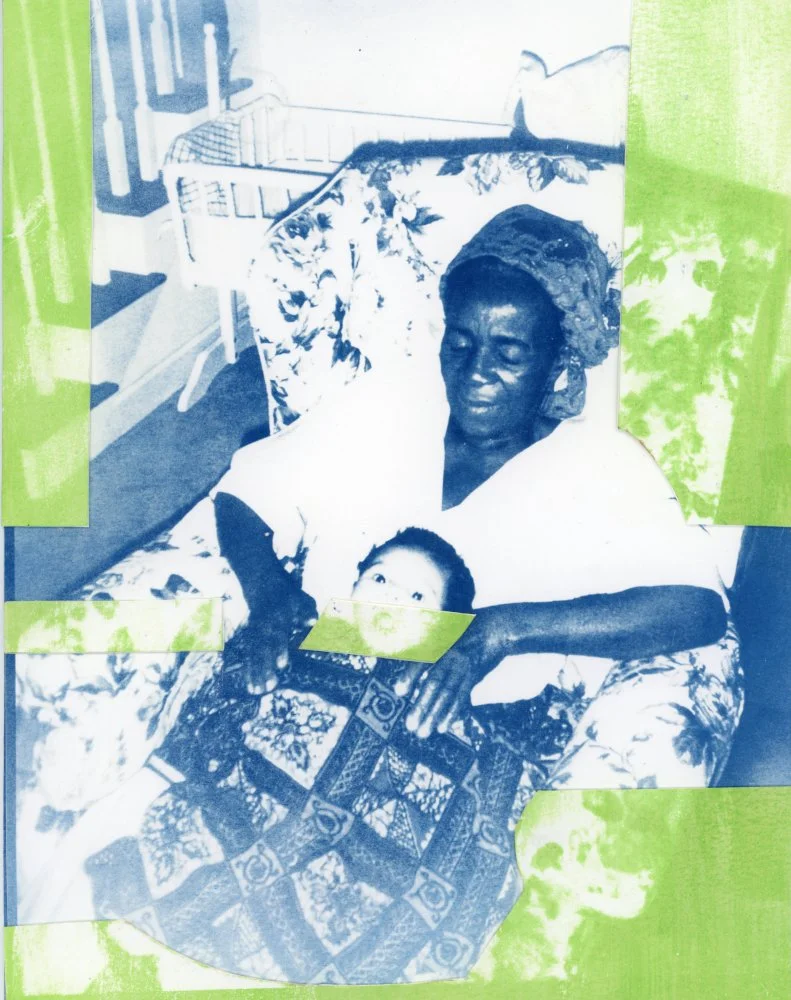

Welcome Home De'De' © De’ De’ Ajavon

Feinstein: For those viewers who may not be familiar with the technical process, can you break that down?

Ajavon: In this project I utilized two different processes: cyanotype printing and gum bichromate printing--the latter being far more tedious. Both techniques require digital negatives, which are inverted images printed onto a transparency paper.

With cyanotypes, a light-sensitive mixture of chemicals is painted onto paper or cloth, with the digital negative on top, and then exposed to light. The print is then washed, and the signature Prussian blue color develops.

Gum Bichromate printing uses an emulsion of gum arabic, watercolor paint, and a dichromate. This emulsion is applied to paper, with the digital negative on top, and then is exposed to light. After it’s developed, the print is rinsed in cool water and the hardened gum arabic is brushed away, revealing an image.

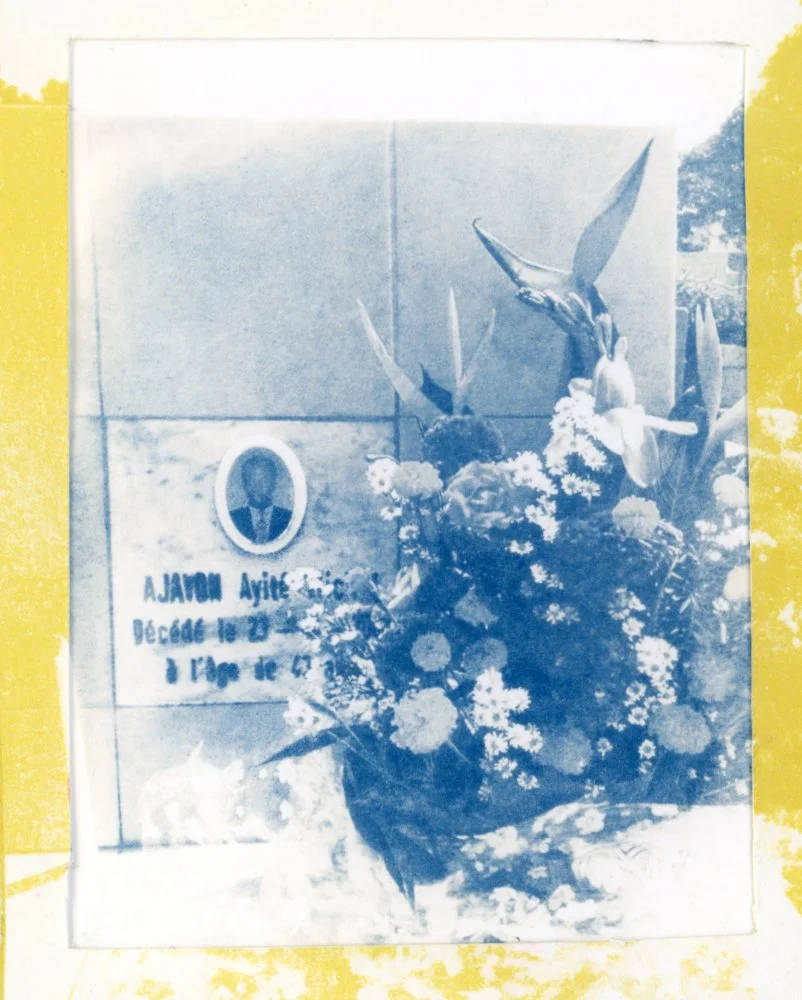

Da. © De’ De’ Ajavon

Feinstein: I'm drawn to the analog jaggedness of your work. I love how cuts and collaging are the opposite of "seamless." I feel a lot of metaphor in that…

Ajavon: I would totally agree! I’m so fascinated with how memory works, and the idea that memories change every time we access them; and also, the ways trauma can change our memories. This weaving and collaging felt like the perfect way for me to visualize the feeling of trying to remember things.

Feinstein: How has making this work helped you to process loss and memory? Do you see photography as being a tool for therapy?

Ajavon: This project has helped me tremendously. Before I started working on this project, it was really difficult for me to look at pictures of my dad without spiraling. I was kind of having this internal emotional war because on one hand, I wanted so badly to look at pictures of him and of us all together --to see my dad and remember him and his essence, but on the other hand, the overwhelming sense of loss was earth shattering.

I finally got some courage and started looking through our boxes and boxes of family photos, and eventually I wasn’t crying sad tears anymore.

Mine. © De’ De’ Ajavon

Feinstein: I can imagine that sitting with this work could help others processing similar experiences of loss and grief. Has this been the case, can you talk about this?

Ajavon: I’ve actually kept this work pretty private – I’ve only publicly shared 1 piece, and only a few close friends and my class have seen it. I needed it to be solely mine for a while because sitting with this work really helped heal my inner child. I can only hope that when people who’ve experienced loss see this work, it resonates with them, and they feel understood.

Feinstein: I really love your use of the word "nebulous" in your artist statement. Why is this such an important part of your thinking/ seeing/ practice?

Ajavon: The word “nebulous” is important to me because when we’re engaging with really intangible topics, like memory and time, the nuance can’t be overlooked. While these concepts can seem vague and sometimes esoteric, I feel like they are things that constantly impact the way we experience life.

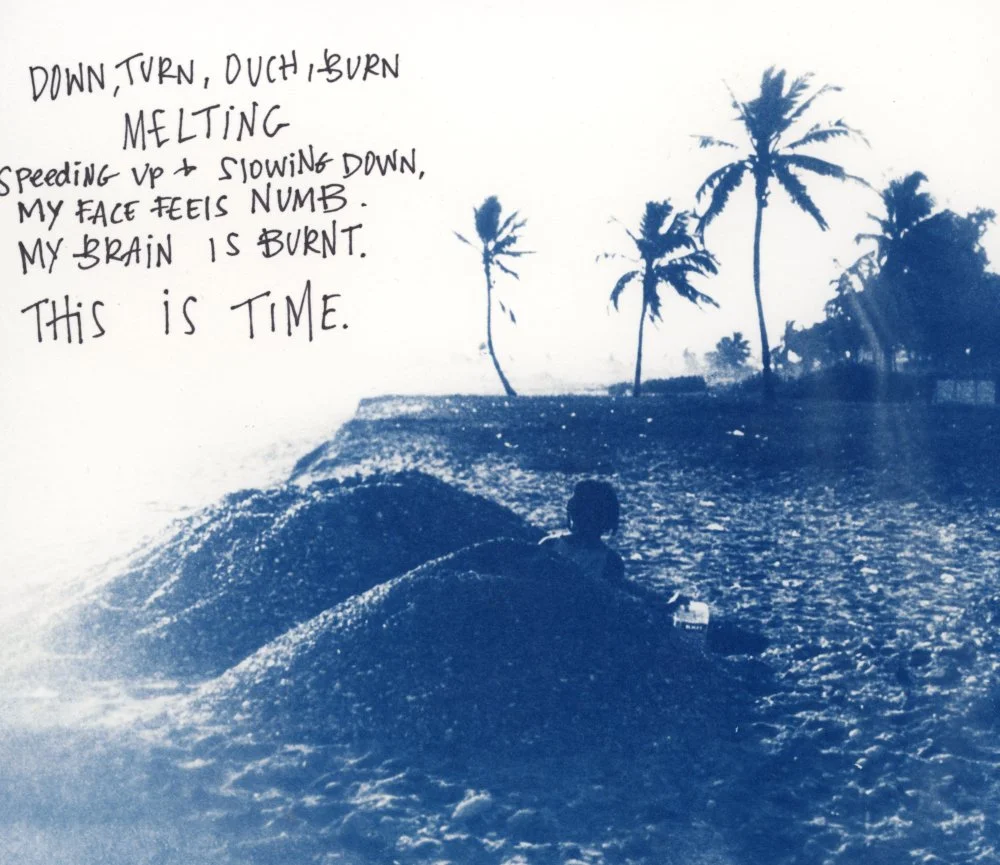

Time. © De’ De’ Ajavon

Feinstein: Can you talk about the use of text in some of the work?

Ajavon: I decided to use text on a couple of pieces in this series, specifically in Time and in 2:23 Gateway. The text in Time is a poem I wrote maybe four or five years ago that I’ve just been holding onto. I thought that it really encapsulated how the passage of time feels. 2:23 Gateway brings in the synchronicities part of the title. There are a few symbolic numbers for my family-- for example me, my mom, and my dad were all born on the 4th day of the month.

In terms of this project, I wanted to present some examples of how much 2’s and 3’s show up. My dad died on the 23rd day of July 2003, at 43 years old. I was born at 2:23 pm. I was 23 when I made this project, and I’ll graduate from college in 2023.After my dad passed, my mom would always see 3:33 on clocks, and after I had a near-death experience in 2018, I started seeing 223 absolutely everywhere. This cyanotype collage is a picture I found of my dad’s old truck, after he had just gotten it, and the license plate had a 2 and 3 on it.

You. © De’ De’ Ajavon

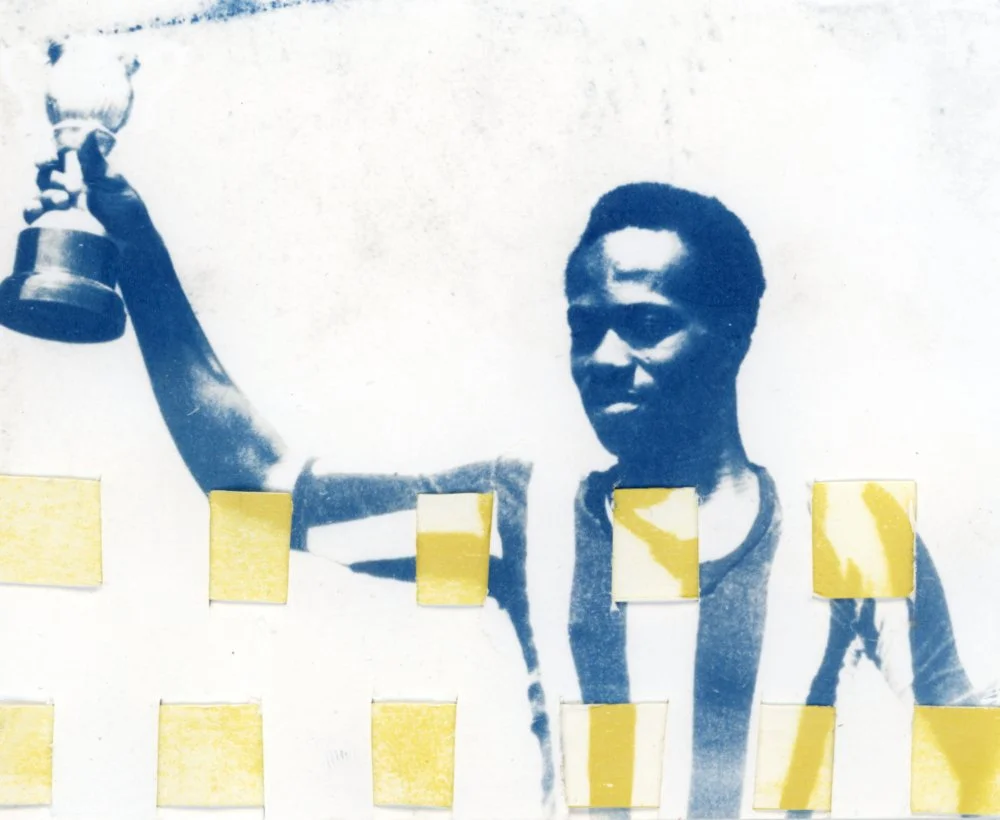

Winner. © De’ De’ Ajavon

Feinstein: Are you still making images for this project/ is it "done"?

Ajavon: I’m not currently working on this project, but I definitely hope to expand on it in the future. While working on this last spring, I actually found out that my dad’s brother Claude had a photo studio and was a professional photographer. My cousin recently went back home to Togo, where my dad was from, and he met with my Uncle Claude, who has decided to give me his old medium format cameras. I’m excited to use them to keep adding to our family archive.