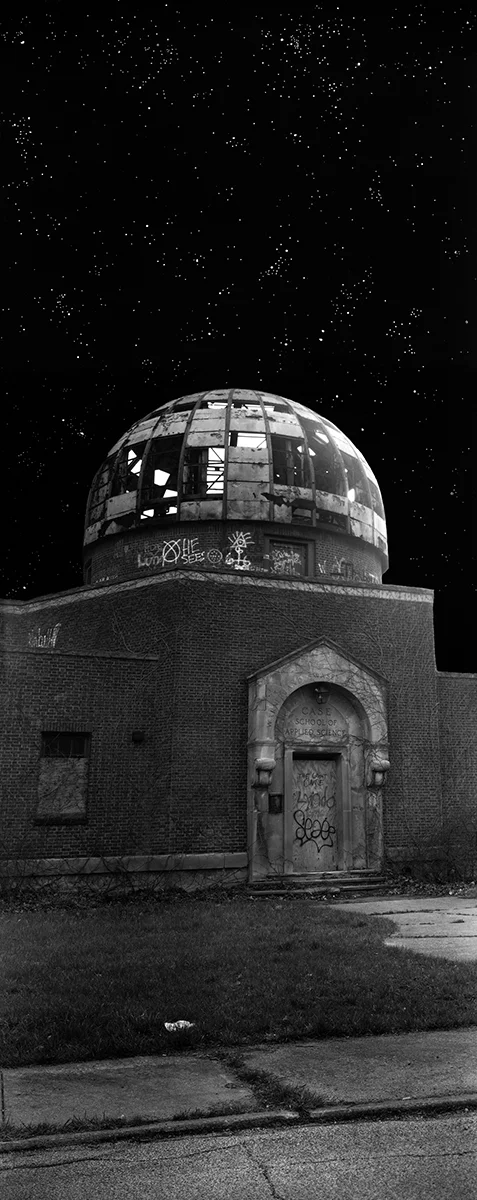

Photo © Ed Eckstein

The Rust Belt Biennial is looking for new photography made in the region.

The United States’ Rust Belt holds an often overlooked place in American history. Once known as a bastion for steel production, industry in the collection of Northeast cities has been in decline since the 1980s. Once thriving cities have been impacted by economic downturn from technological shifts and companies moving business and production overseas. As one might expect, it’s been a pivotal area during election periods when candidates attempt to reach its disenfranchised, yet voting-heavy population.

Seeing its unique position in American history, curators Niko J. Kallianiotis, Dana Stirling and Yoav Friedlander came up with the idea of hosting a biennial for photography made in the region. The exhibition opens in August at Wilkes University’s Sordoni Art Gallery in two parts: one part artists who have been invited to participate, and an open call juried by photographer Andrew Moore, with a deadline coming up on June 28th.

I emailed with Stirling, Kallianiotis and Friedlander to learn more. We’ve included some of the pre-selected images of the region to give folks a sense of what to expect (and maybe take a hint toward what the curators are looking for!)

Jon Feinstein in conversation with Niko J. Kallianiotis, Dana Stirling, and Yoav Friedlander

Photo © Lori Nix and Kathleen Gerber

Jon Feinstein: How did you come up with the idea for this project?

Niko J. Kallianiotis: The goal of The Rust Belt Biennial is to create a dialogue between the photographic community and people who are not related to the arts. I was pondering the idea for some sort of a festival that would bring the community together for a while and my main concern and inspiration you can say was how the mainstream media misrepresented the region both in regards to the landscape and the people living in it. For example, I was out photographing about three weeks ago in Plymouth, PA, and a store owner came out asking questions. “Why do you photograph?’ she asked in a concerned and skeptical tone. I am just photographing some store windows, I replied. She was worried that I was from a Philadelphia news outlet which came to the town a while back representing the place and the people in a very bad tone; see elections.

I asked Yoav Friedlander, who has a great interest in the region, if he would like to come onboard and he accepted the invitation. I thought: we are both foreigners, we both work in the Rust Belt regions, and we share the same ideas about how photography has been used to represent this region.

Yoav Friedlander: On our first drive through Scranton, PA seeking for industrial signage and typography inspiration I was struck by what I saw and already started photographing for myself. Niko was generous and took me to places that added context to what I’d seen around me. I felt an urgency to capture the state of the region. I made many trips over to Old Forge, PA, where Niko lives and where we did the book design and edited the sequence. Niko had this drive of creating something that can better the situation around him that is also related to our mutual passion - photography. He mentioned several ideas that we will probably get to do in the future but then he said - why don't we make our own festival with work from the region! We will call it the Rust Belt Biennial! I immediately jumped on board. I felt the need to do something beyond taking (pictures) I wanted to be able to give back as well!

Photo © Dave Jordano

Dana Stirling: I think the Biennial came up in a very organic way.

When they came together they always spoke about the large roster of artists in the region that are as important and as good as many mainstream photos out there, yet sometimes they are not highlighted – if because of political and cultural differences or just the lack of awareness. It always came down to giving back to the community and shining a light on its artists.

Feinstein: I'm interested in your own backgrounds and how it might tie into this. Yoav and Dana: you're originally from Israel and Niko, you are from Greece, and are all living and working in the United States. Why is this region particularly of interest to you?

Kallianiotis: As a Greek living in the United States and experiencing both the urban and rural landscape I have developed a close relationship with the latter. The region is of interest to me because as an immigrant and one who came to the United States before the internet era, the developing knowledge, if you were to call it that and the overall ideals and symbols of American society were experienced though the Hollywood screen. Moving from NYC to Penn., became an educational experience of what America is and through my past occupation as a newspaper photographer in Ohio, NY state and Penn., open many other ways of thinking, evaluating and interpreting. You can say that I have developed and insider/outsider perspective.

Stirling: I’ve been traveling often with Yoav to Pennsylvania as he’s working on his project in the region. The area is a very visually stimulating place for a couple of photographers like us – it goes from one extreme to the other in a matter of one town down the road. You can see decay, condemned and run down houses alongside a beautiful Coca-Cola mural that reminds you that these places, with all the hardships and the ups and downs, has a rich cultural history that should be documented and celebrated. I think, like any place, there is the good and bad in it - you just need to find what you are captivated by and share it with others that might not know much of it.

Photo © Michael Froio

Friedlander: As an Israeli who lives in the US, not yet a citizen, I’ve been trying to make sense for the past 7 years being here, what is my function, contribution, voice, identity. I am sure it is an internal struggle common to an immigrant. Niko is like family to me and working with him on his book about Pennsylvania was a unique experience, yet it didn’t anchor me to the landscape yet. It was the Saint Nicholas Coal Breaker (serendipitously the same saint Niko is named after - his namesake) and its eradication that turned me into an integral part of the landscape.

Niko took me over to Mahanoy City, right before the town, from an overpass I saw an eerie looking structure and I banged on the car window trying to say - TAKE ME THERE - he was laughing, and said “that’s where we are heading”. I took a couple of photos of the Coal Breaker, at one time the biggest in the world, and a source of great pride. Months later on my way back from a trip west to Pittsburg I rushed east to capture Saint Nicholas in the snow, hoping to get before sunset. I arrived at its footsteps as the sun started setting behind the hill. I only managed to capture one angle as the shadow of the hill was climbing up the structure. What I did not know at those very moments was that this was going to be the last sunset on the Saint Nicholas Coal Breaker. The day after it was demolished. Taken to the ground. Inadvertently I inserted myself to Pennsylvania’s long history with Coal.

Photo © Jeffrey Stockbridge

Feinstein: How did you select Andrew Moore as the juror? What does he bring to the table, specifically related to this topic?

Stirling: I think when you see Andrew’s images, there is no doubt that he is the right artist to jury the first Biennial. Andrew’s work has a way of being so specific in time and place – you are able to transport to these places. I always found his images to be portraits of times that passed and he is the archivist of these memories. With all that said, Andrew knows what it means to document a place and allow the photographs to speak for its history as he’s done in every place he visited himself.

Friedlander: I believe Andrew’s book, Detroit Disassembled, represents many of the reasons we wanted him to be the juror for the biennial open call for submissions. He was there to capture the aftermath of the collapse of the big industries, creating a bridge between a great past and a current state of affairs. I myself was his student and thereafter his assistance for a couple of years. I know how he considers and assesses the value of photography from different perspectives - aesthetic, concept, context, historical importance. We wanted to turn the attention of a great master of the medium to work done by people of the Rust Belt region and work made in it.

Feinstein: Why a Biennial?

Stirling: I think in order to create something really great, that has value you need to give yourself time. As we are only starting this vanture, and we still have to learn and grow, having that time gives us the chance to explore different ideas and execute them in the best way.

While it's geographically somewhat different, when I think of "The Rust Belt," I think of it as being synonymous with "flyover country" - especially in the context of the growing political divide in the United States. Is this at all a driver in the biennial?

Friedlander: The political divide perhaps was the catalyst to create the Rust Belt Biennial, but it certainly doesn’t take part in it. It was the misrepresentation on media outlets, the bias, and more than anything else the neglect of a region that not so long ago meant everything America was proud of. The Rust Belt region has a lot to offer. The people are the same people sans a great demand for some of the skills they were once known for. There are stories to tell and a future to build. Making the biennial specifically within the region is all about strengthening a local community believing that the current situation is not permanent and there is where to grow from here.

Stirling: I think politics is a part of anything we do today – if we want it or not. The political climate submerges itself in art in general. But when speaking about the Rust Belt, it is very clear that there is a political burden around it – left or right – we all have opinions that drive us and move us in one way or another. However, I don’t think the political aspect of the region motivates the Biennial itself. We come from a place of true admiration to the area and a need to not only be outside spectators but active members of the art community and by putting a small dent in the scene we are able to share works of talented artists that will have their works speak for themselves and their views.

Photo © Lisa Elmaleh

Feinstein: Aside from putting together what I'm sure is going to be a strong exhibition, what legs do you see this having/ what do you hope it accomplishes or communicates on a broader scale?

Friedlander: Many of us today attempt to reach the global audience - make work that is appreciated internationally and seen by many. I feel that in the process we are overlooking locality, and to that extent neglecting the small communities that we live in. Looking at photography specifically many of the instagram followers of a successful photographer, lets say, will be photographers themselves and photo enthusiasts.

In contrast to this reality I look at the wonderful Sordoni Gallery in Wilkes University, where the Rust Belt Biennial will be held. I follow their posts on social media and what I find is locals - children and adults - who are not artists themselves come to the gallery to experience what it has to offer. This I believe is the greater purpose that we aim for and where we are aspiring at a broader scale - reaching people who are not colleagues or photographers. Beyond that we are looking to eventually offer workshops and skill building in photography to the region.

Photo: © Lauren Orchowski