To declare that wrestling is homoerotic isn't necessarily a new or groundbreaking statement. Art historical references aside, a simple Google search pairing the two words returns countless blogs dedicated to driving the connection home. However, photographer Ben McNutt expands on this ongoing conversation using appropriated historical images, photographs of ancient Uffizi wrestler sculpture, and studio portraits of young college wrestlers to emphasize the erotic gestural qualities of the sport in history and present day. He intertwines these images to ask viewers why a mainstream, often homophobic culture might assign straight identities to a male dominated tradition with clear sexual tension. We spoke with McNutt to learn more about him and his practice.

JF: Is wrestling as a sport is inherently homoerotic or is it more the social context and associations? Do Greco-Roman art-historical tropes have any influence over this?

BM: It's just harder to deny compared with other sports. One can point it out in football, lacrosse...but wrestling is more "in your face" about it. In collegiate wrestling it's about two men and a point system where you ultimately aim to pin your opponent against a mat. People like to jump around seeing homoeroticism in sports. Men grab each others asses in football. Men hug each other in soccer. With wrestling there is just no way in denying its tendency to be seen in a homoerotic light, even as a so-called joke.

Tell me a bit about the Uffizi Wrestlers?

There is a copy of the Uffizi Wrestlers located in the atrium of MICA, the school I attend. It's this real shitty plaster cast that the college used for life drawing classes in the early 1900's. It just sits in a corner, completely unnoticed by the hundreds of people that walk through the building everyday. I noticed it three years into attending and then for months I took a 4x5 camera with me and I really looked at the statue. Like actually spent the time to take it in. And it was weird. It's this emotionally gripping sculpture whose viewpoints change depending on where you're looking. And then I Googled it, and the history of the statue is just as strange as its existence in the school. The sculpture has a ton of different names, The Wrestlers, Wrestlers, The Uffizi Wrestlers, The Two Wrestlers. The original marble statue the dozens of copies are based off of is located in the Uffizi Gallery in Italy, yet the sculpture itself is a roman copy of a lost greek bronze. Stranger yet, the heads were added onto the statue hundreds of years later after they were rediscovered and excavated in the 1500's. It was a really poignant statue that I felt talked about a lot of the issues I had with wrestling. It's agelessness. It's violence. It's sensuality. Right there, hidden in plain sight.

Your work is a mix of found images, photos of classical sculpture, portraits and even some staged tableaux. Why is this important?

I didn't actively start the project looking to include different types of representation for what I wanted to talk about with wrestling. The more I got enveloped in the sport, the more I just began to come across images that I wanted to collect and use. They act as a pointer device to say, hey, look at that, two men grasped together in a commemorated stamp used by the United States Postal Service. Having a large pool of imagery to choose from is motivating. It's weird and exciting to pair together a portrait I've taken with a portrait of two wrestlers from the 1900's. All of these materials are part of a collective history that is evolving with the work.

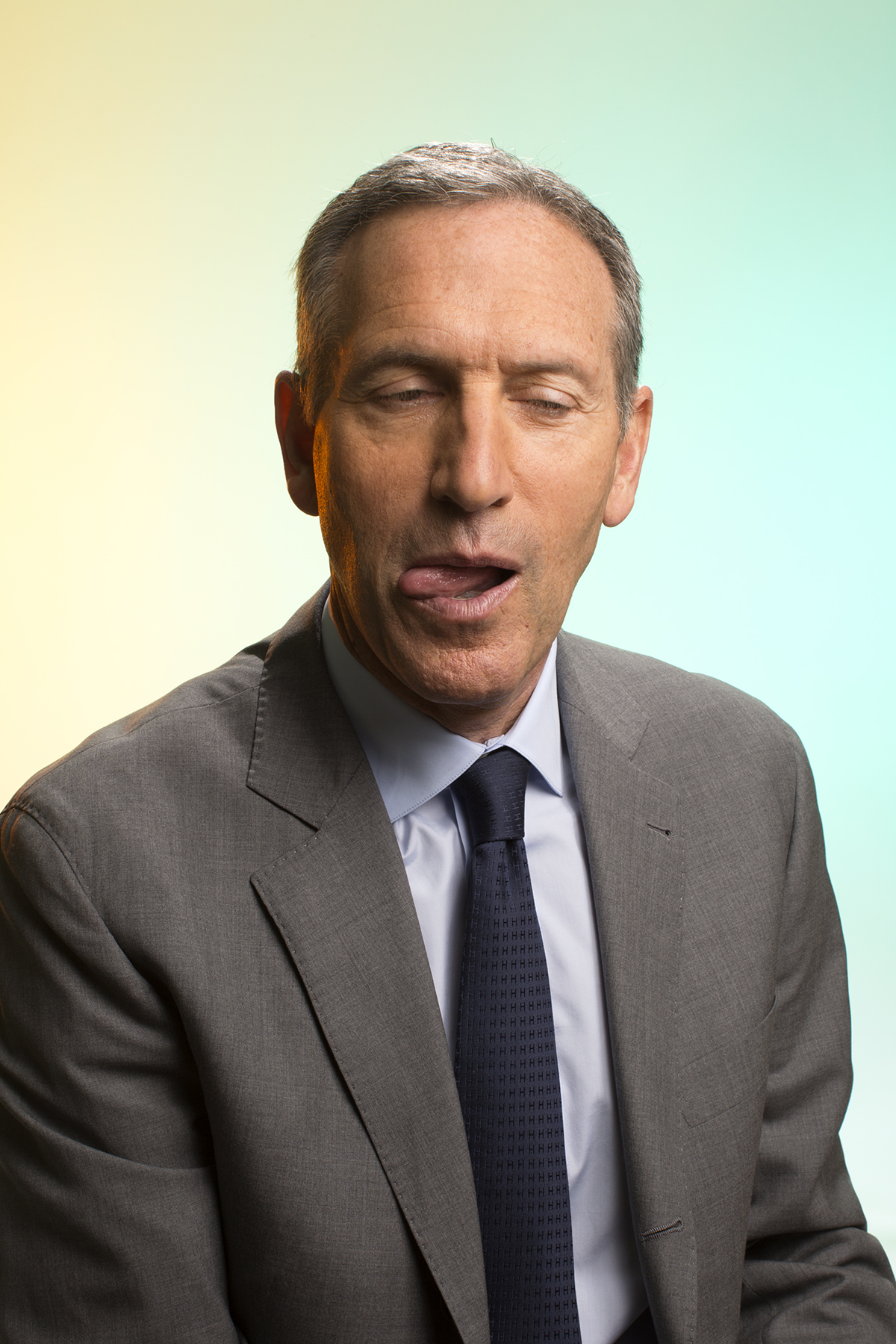

When your work was published on Vice and Huffington Post, some commenters remarked that these ideas are "nothing new", that “duh – of course wrestling is homoerotic…” -- how do you respond to that? How is your work expanding on an existing conversation?

And I'm really glad it's obvious to people. I want to point out that out. But there is a lot more going on than just pointing it out, there is a further conversation to have from it, even if it's about how obvious it is. There are a lot of social conditions allowing the type of interaction one might see in wrestling to be acceptable to larges numbers of people from hugely different backgrounds across the world. Outside of certain contexts that behavior is not so acceptable. It really comes down to context. A guy wrestles a guy outside in a park in and it's a whole different meaning to a whole bunch of people. And it's certainly not always accepted by people. Why is that? It seems so twisted.

Did you wrestle growing up? Was it something that was encouraged in your family or community?

I think this is a really interesting question because it gets brought up by anyone viewing the work. A lot of people really need to know if I wrestled, or they assume I didn't wrestle, or they assume I don't do any type of physical activity at all. It's some sort of validator people have with the work. They want to know if I have an insiders look or an outsiders look on wrestling. I didn't wrestle growing up and it wasn't present in my community. To some it seems unfair to make work about wrestling if I didn't wrestle. I don't think that makes any sense. I love wrestling. I love it a lot. I love learning about it. I love reading about it. I love learning techniques. I love the sport. It's not something I grew up with, but it's something I am growing with now.

BIO:

Ben McNutt is an artist pursuing a Bachelor of Fine Arts in photography at the Maryland Institute College of Art in Baltimore, MD. Ben observes acts of homoeroticism intertwined in masculinity throughout history and utilizes artistic media as a vehicle for displaying these observations. Ben was most recently interviewed about his wrestling work for Vice on Huffington Post Live. If you like his work, you should really buy his edition of Matte Magazine.