David Brandon Geeting never expected to be a successful commercial photographer. He attended the School of Visual Arts in New York City as a photo major with little interest in studio lighting, or the slightest notion that he might one day be commissioned to travel the country to photograph the entire 85th Anniversary Issue of Bloomberg Businessweek. But he did, and over a few short years, has quickly become one of today’s most inspiring photographers to watch. His jarring flash, off-kilter methods of arranging still life, and unconventional style of shooting celebrities have radical ties to, and little visual distinction from his personal work. Without consequence, many of his unpublished outtakes have found their way into his own projects.

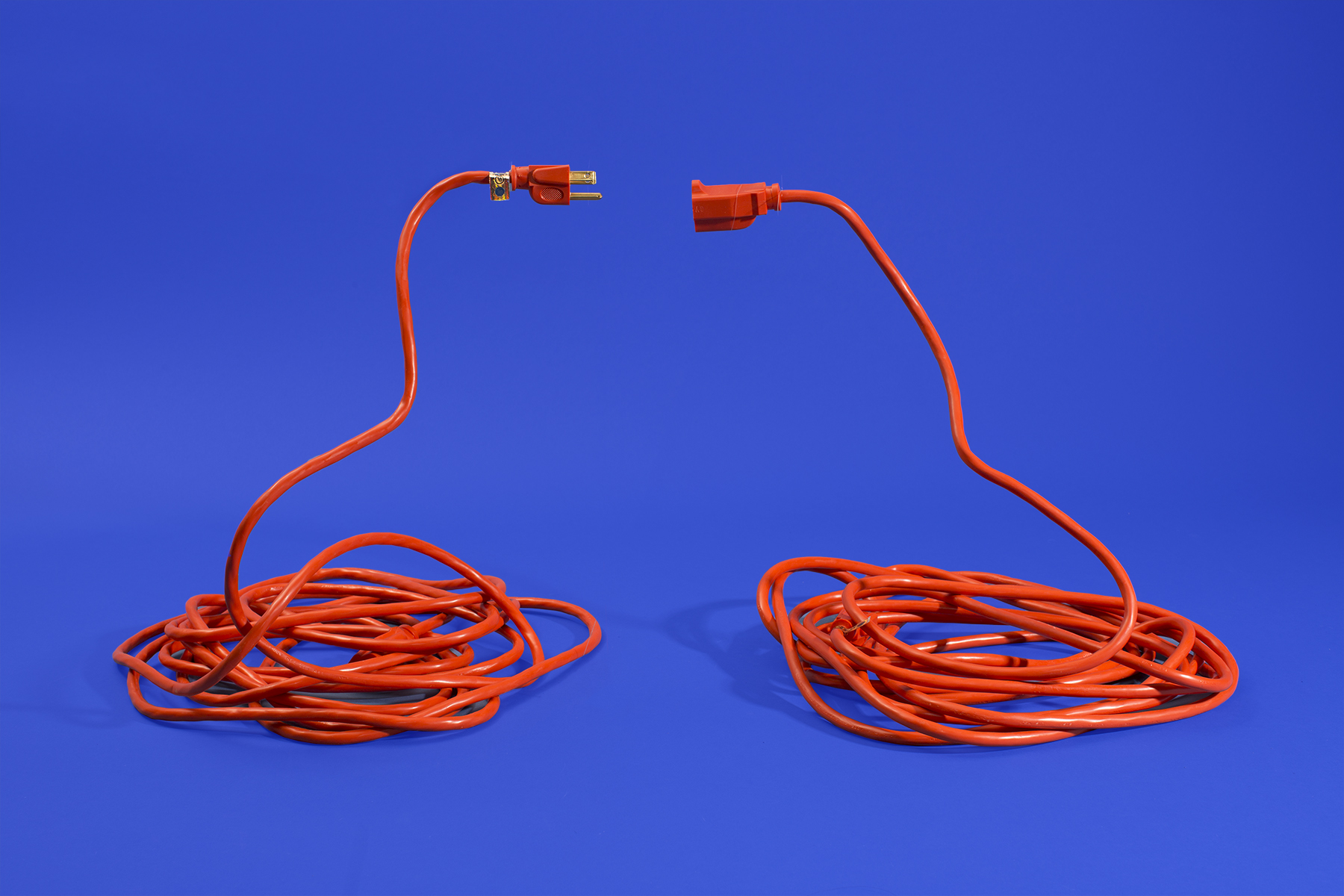

Shortly after graduating from SVA, Geeting assisted Peter Sutherland, who gave him his first digital SLR. Building on his undergrad tendency to wander the city making photographs of garbage, he began making what he calls ‘Frustrated Art.’ Geeting writes: “It’s the kind of art you make when you have all kinds of pent up creative energy and no ideas on how to release it. I would start to go through cabinets of junk in my house and throw still lifes together out of really boring materials and blast it with a flash and post these on my blog.”

Eventually, Bloomberg Businessweek photo editor Emily Keegin got wind of his work and hired him to photograph the inside of a 3D printer factory in South Carolina. "David came into the office to show me his work a few months after he had graduated from SVA," Keegin tells us. "He carried his portfolio in a plastic shopping bag, and it was the best book I had ever seen--- I think primarily because it was just a bunch of art work. He wasn't trying to be someone he wasn't. I liked the way he saw the world & felt like the magazine was in need of his kind of quirk."

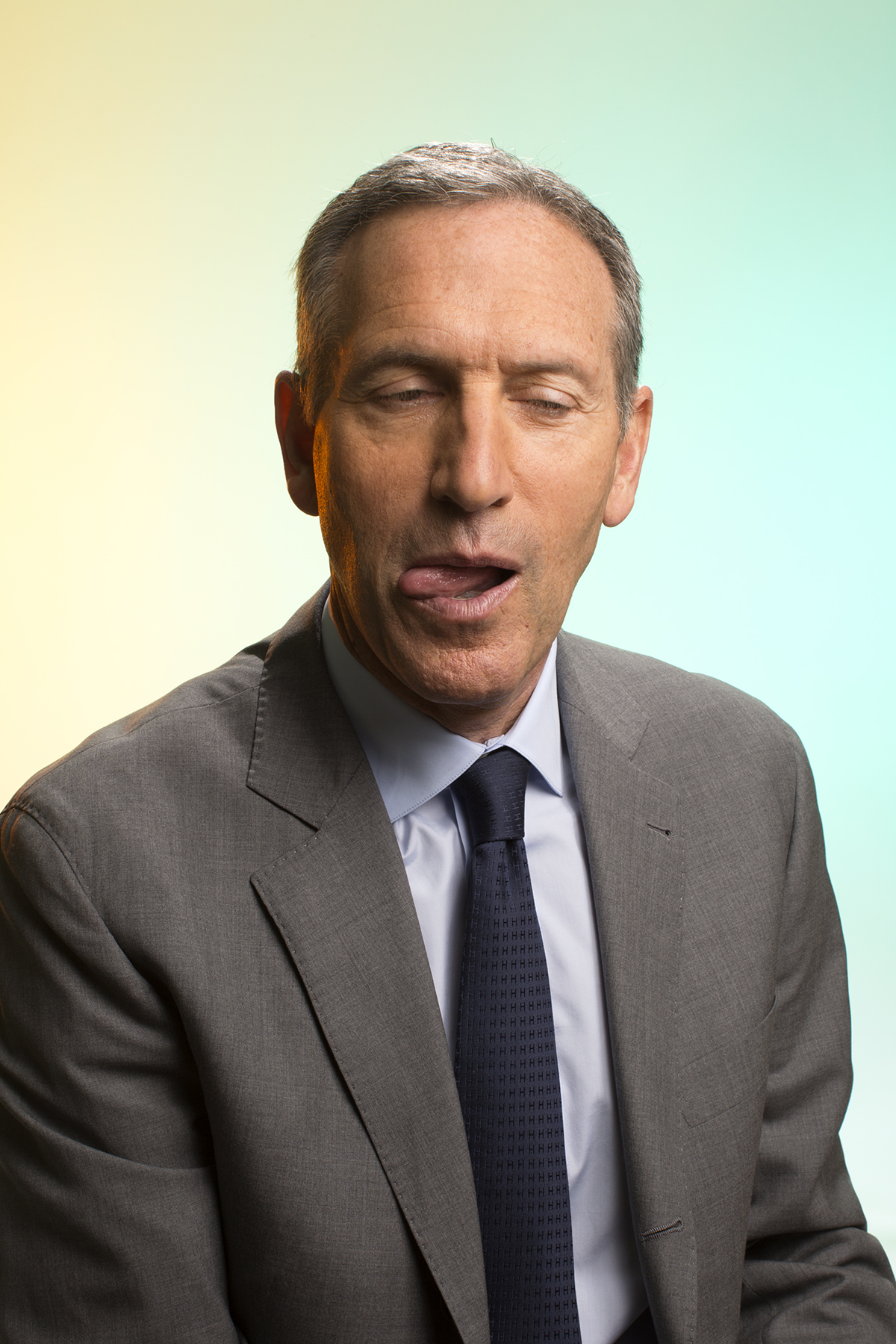

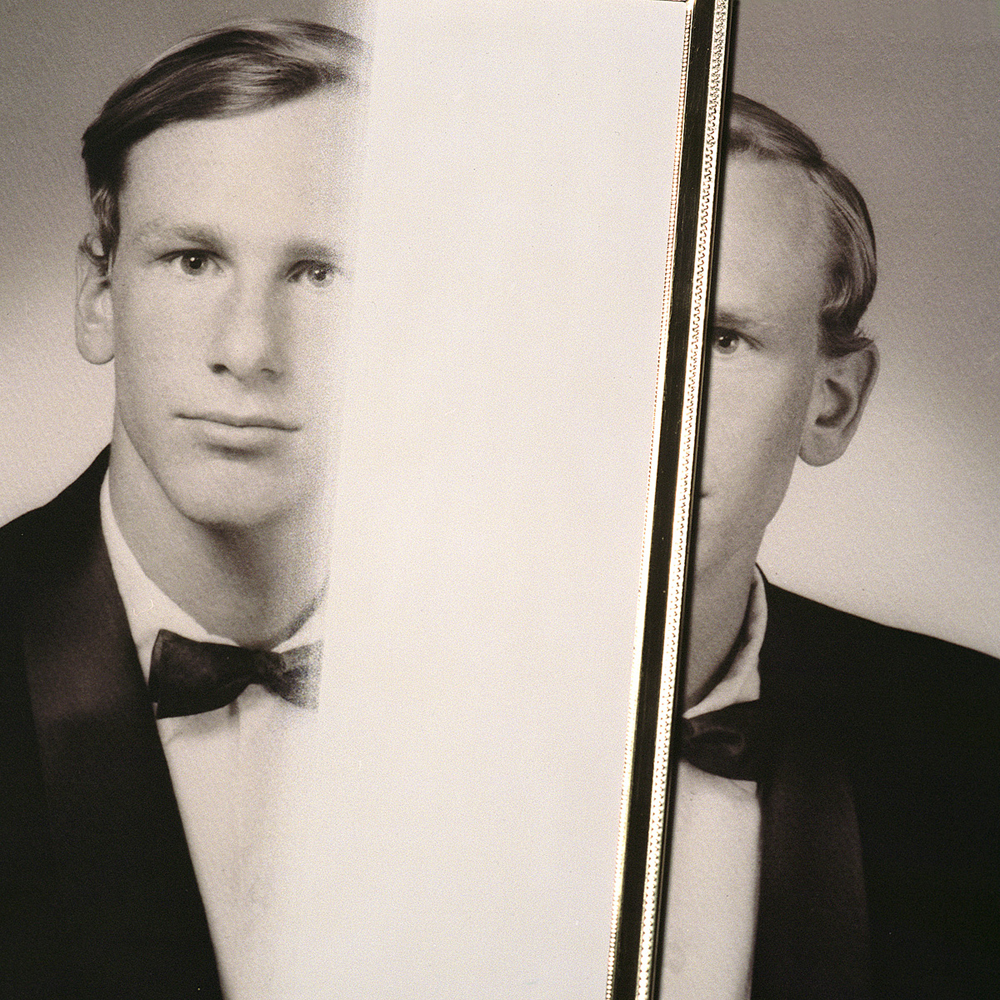

Since then, Geeting has shot countless jobs, applying his slicked-up trash aesthetic to everything from product shots to tech innovators. Some of Geeting’s most surprisingly discordant and personally rewarding images have come out of spontaneous collaborative moments on shoots. His adventurous, experimental approach gives them multiple readings in and outside of their commercial intent.

“One of my favorite images,” says Geeting “is a photo of my friend Corey wearing all black looking real goth, holding a state-of-the-art blender and standing in front of a wide array of fruits and vegetables. We were shooting stills of a fake Vitamix infomercial and Corey was assisting me that day. In the photo he was just a stand-in for me to test the light, but when I look at that photo out of context it conjures all kinds of ‘WTF's. "

Geeting’s philosophy towards his personal, editorial and commercial work, and everything in between is honest and straightforward. It finds strength in pushing comfort levels, taking ongoing creative risks and being unafraid to openly play with the most absurd of ideas.

“I think they are about open-mindedness and not being afraid to make connections between things, no matter how disparate they may seem. I also think they are pictures about making pictures, referencing both technical issues and concepts gone awry. My favorite images are always the wrong ones.”

Bio: David Brandon Geeting (b. 1989) is an American artist born in Bethlehem, PA and currently residing in Brooklyn, NY.